Two naturally occurring substances appear to correct a cellular defect that may lie at the root of cystic fibrosis (CF). The new findings, although preliminary, hold out the hope of blocking the progressive lung damage wrought by CF and perhaps extending the lives of many children and young adults who suffer from this deadly inherited disease, the researchers suggest.

Cystic fibrosis strikes one in every 2,500 babies born in the United States. The disorders causes epithelial cells lining the lung's airways to absorb too much sodium and secrete too little chloride. This double defect leads to a buildup of thick, sticky mucus that clogs the breathing tubes. The mucus-layered lungs become vulnerable to frequent infections--a process that destroys healthy lung tissue, impairs breathing and usually causes death by age 30.

Last year, researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill reported encouraging results in treating CF with an aerosol form of the diuretic drug amiloride (SN: 4/28/90, p.260). The study, which involved 14 patients, suggested that amiloride helps inhibit sodium absorption. Now, in the Aug. 22 NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE, the same group reports that two different compounds, both classified as triphosphate nucleotides, attack the other half of the CF equation: the chloride deficit. Together, the findings hint at a double-barreled approach to treatment.

"Ultimately our goal would be to give these drugs [amiloride and triphosphate nucleotides] in combination at a very early age to protect the airways," says Michael R. Knowles, who co-directed the new study. If all goes well, such treatment may prevent the devastating lung damage that leads to premature death for CF victims, he told SCIENCE NEWS.

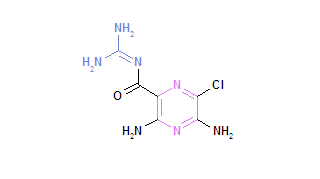

In the new work, Knowles, Richard C. Boucher and their colleagues studied 12 men and women with CF and a control group of nine men and women in good health. Using a thin tube, the researchers squirted solutions containing either adenosine triphosphate (ATP) or uridine triphospate (UTP) onto epithelial cells lining the nose -- using the nasal tissue as a model of airway epithelial cells deep within the lungs.

In all volunteers, the ATP and UTP solutions increased the amount of chloride secreted by nasal epithelial cells. However, the CF patients showed such a strong response that they ended up with chloride secretions that equaled those of the controls. With the nucleotide treatment, "you fully correct the abnormal chloride transport," Knowles says.

ATP and UTP are energy-producing substances normally present within cells. But the new research suggests that these compounds can also bind with protein receptors sitting on the exterior of the epithelial cell, thereby triggering an increase in the cell's chloride secretion.

Boucher says his inspiration for the ATP-UTP experiment came from a "truly serendipitous" discussion with a researcher who worked with these nucleotides.

He and his colleagues acknowledge that they have yet to demonstrate the efficacy of safety of ATP or UTP for treating CF. However, their hope is that such compounds, used together with amiloride, would lower the number of lung infections and extend the life span of people with CF, Knowles says.

Pamela B. Davis, who studies cystic fibrosis at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, calls the new work an "excellent start" toward the goal of improved treatment for the disease. In an editorial accompanying the research report, Davis writes: "The need is urgent, because every day three more patients die of cystic fibrosis."

COPYRIGHT 1991 Science Service, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group