Speak Up!

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence is about to hand down judgement on the newer range of anti-psychotics. Tony Gillam suggests that prescribers and mental health professionals have some questions to ask themselves as a result

We all have patients who are unreliable about taking their medication. Sometimes, it seems, people who take medication as prescribed are the exception rather than the rule. Some estimates suggest that up to 80% of patients with psychosis do not comply properly with treatment. Whether we call it compliance, concordance or conchiglie, it remains a stumbling block for patients, their families, carers and CPNs.

The consequences of poor compliance with medication in psychosis have a sad inevitability about them, like an accident waiting to happen. Relapse, sooner or later, and often readmission. Psycho-social approaches, such as family interventions, help promote compliance but these may be doomed to failure without effective maintenance on anti-psychotic medication.

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) is about to announce its guidance on the use of atypical anti-psychotics. The debate about the availability of Beta Interferon for patients with multiple sclerosis attracted a lot of press attention. It is doubtful whether the plight of people with schizophrenia will elicit the same degree of interest from the media. Who cares what treatment is available for schizophrenia? Typical, atypical, what does it matter?

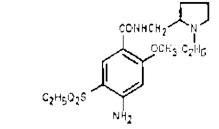

The first answer is: compliance. It's no good having effective medication if patients either forget to, or refuse to, take it. Their reasons for rejecting traditional anti-psychotics are clear. They tend to cause a higher incidence of extra-pyramidal side effects. The atypicals (such as clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, amisulpride and quetiapine) are less likely to cause extra-pyramidal side-effects and perhaps this explains why patients seem more willing to take them.

This is not to say atypicals are problem-free. All drugs have side effects - clozapine, for instance carries a risk of agranulocytosis, hence the need for routine blood monitoring. Weight gain can also be a problem with any anti-psychotic (although quetiapine appears to have a neutral effect on weight in the long term). Increasingly, patients seem to be complaining of sexual dysfunction, due to an increase in prolactin levels. The risk of extra-pyramidal side effects, weight gain and raised prolactin levels can all lead to poor compliance, to relapse and rehospitalisation. As professionals, would we take anti-psychotics if we developed schizophrenia and which medication would we choose?

This is the second point: choice. People with schizophrenia may be offered a depot injection or tablets. If offered the choice of oral medication, they may be offered the option of an atypical. How many, I wonder, are offered a choice between atypicals? NICE has to decide how much choice prescribers will be given and we, the mental health professionals, must decide how much choice we want for our patients.

Tony Gillam is a CPN with Worcestershire Community Mental Health Trust.

Copyright Community Psychiatric Nurses Association Mar/Apr 2002

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved