Endogenous endophthalmitis is a potentially blinding ocular infection resulting from hematogenous spread from a remote primary source. The condition is relatively rare but may become more common as the number of chronically debilitated patients and the use of invasive procedures increase. Many etiologic organisms (gram-positive, gram-negative and fungal) have been reported to cause endogenous endophthalmitis. Risk factors are well defined and include most reasons for immune suppression. A high clinical suspicion is needed for early diagnosis and treatment. Early intravenous antibiotic therapy remains the cornerstone of treatment. The roles of intravitreal antibiotics and vitrectomy are evolving and may become more widely accepted as therapeutic modalities. The authors report a case of endogenous endophthalmitis and provide a brief review of the literature. (Am Fam Physician 1999;60:510-4.)

Endogenous endophthalmitis is defined as an intraocular infection resulting from hematogenous bacterial spread. It is relatively rare, accounting for 2 to 8 percent of all cases of endophthalmitis, and is associated with immunocompromised states, debilitating diseases and invasive procedures.1 Because of the rapid advance of medical technology, a longer life span of patients with chronic diseases and a rising prevalence of long-term intravenous access, the disease may become more common in clinical practice. It is important that the family physician be aware of endogenous endophthalmitis because early diagnosis and prompt aggressive treatment are imperative if vision loss is to be avoided.

Illustrative Case

A 70-year-old woman presented with a five-day history of progressive blurring of vision and pain in the left eye. She had not experienced trauma, fever or chills. The patient had diabetes mellitus, decubitus ulcers and end-stage renal disease; she had recently started hemodialysis therapy. She was afebrile. Ocular examination revealed left upper lid erythema and edema with ectropion of the lower lid (Figure 1). There was marked proptosis with a profuse, thick, purulent discharge (Figure 2). The eye had no light perception or motility, and ciliary injection as well as diffuse subconjunctival hematoma were present. Fibrin was seen in the anterior chamber. Funduscopic examination showed diffuse vitreal debris with old vitreal hematoma and fibrosis. The area around the subclavian dialysis catheter showed no erythema or suppuration. A grade 2/6 systolic murmur was audible at the apex, and a clean, stage 4 decubitus ulcer was present in the sacral area.

The white blood cell count was 14,000 per mm3 (14 3 109 per L), with 87 percent neutrophils. Conjunctival culture showed a heavy growth of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Blood cultures remained negative. A computed tomographic scan of the head showed diffuse scleral thickening of the left orbital space with preseptal inflammation and proptosis (Figure 3).

Ultrasonography of the eye showed dense vitreous opacities. Echocardiography revealed no vegetations. The patient was given vancomycin and gentamicin, and underwent enucleation on the third hospital day. Pathologic examination showed massive inflammation throughout the globe, consistent with panophthalmitis. Gram stain showed clusters of gram-positive cocci in the vitreous and cornea.

Classification

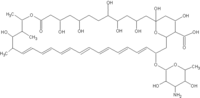

Endophthalmitis is broadly classified as exogenous or endogenous (Figure 42). Exogenous endophthalmitis is associated with an extrinsic portal of entry. Endogenous endophthalmitis implies a bloodborne infection related to bacteremia. A classification system introduced by Greenwald3 takes into consideration the affected areas of the globe and the associated visual prognosis. Focal endophthalmitis responds well to intravenous antibiotics and generally results in minimal sequelae. Posterior diffuse endophthalmitis and panophthalmitis are associated with a much poorer prognosis; often these conditions lead to blindness, atrophy of the globe or enucleation.

Epidemiology

Endogenous endophthalmitis can occur at any age and has no sexual predilection. The right eye is involved twice as often as the left eye, because of the more proximal and direct blood flow to the right carotid artery.3 Bilateral involvement occurs in approximately 25 percent of cases.

The population at greatest risk includes immunocompromised patients with leukemia, lymphoma, asplenia or hypogammaglobulinemia, and patients taking immunosuppressive therapy, including corticosteroids.3 Chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency and malignancies also increase the risk because of compromised immunity and the increased likelihood that the patient will undergo invasive procedures. Persons with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) may also develop endogenous bacterial retinitis, but surprisingly few cases of endophthalmitis have been reported.4 Alcoholics have an increased incidence of this disease. Intravenous drug use is specifically associated with Bacillus cereus infection and fungal endophthalmitis.

Microbiology

The patient's risk factors may help the physician predict the etiologic agent or narrow the list of potential organisms. Gram-positive organisms are the most common bacterial pathogens, especially the streptococcal species, including Streptococcus pneumoniae. Staphylococcus aureus is found more often in patients with diabetes mellitus, renal failure, cutaneous infections or intravenous catheters. Infected arteriovenous fistulae have also been reported as a source of staphylococcal infection.1 In the past 10 years, B. cereus has become a common bacterial agent in intravenous drug users.3 It is an aggressive agent, leading to blindness if antibiotic therapy is not instituted very early.

Gram-negative organisms are also sometimes encountered. Neisseria meningitidis was the most common pathogen in the pre-antibiotic era.3 The number of cases of endophthalmitis related to Haemophilus influenzae is expected to decrease with the advent of vaccination, paralleling the documented decrease in meningitis.5 Cases of endophthalmitis related to Escherichia coli and Klebsiella have been associated with diabetes, liver disease and urinary tract infections.6,7

Candida is the most common organism causing endogenous endophthalmitis.8 Risk factors for infection with this organism include intravenous drug use, surgery, malignancies, intravenous hyperalimentation, endovascular lines, diabetes, neutropenia and the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and immunosuppressive medications, especially corticosteroids.9 The classic finding is white chorioretinal infiltrates with fluffy white vitreous opacities described as a "string of pearls" appearance.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

A high degree of suspicion is necessary to make an early diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis. Patients commonly complain of eye pain, blurring of vision, ocular discharge and photophobia.10 The risk factors mentioned above should be elicited, in addition to symptoms that suggest the presence of the primary infection. Patients who present at a later stage in the disease may have obvious signs such as chemosis, proptosis and hypopyon. Earlier signs such as Roth's spots (round, white retinal spots surrounded by hemorrhage) and retinal periphlebitis can be seen using funduscopy. Slit lamp examination and ocular ultrasonography should be performed to look for anterior vitreous haze echoes and retinochoroidal thickening. Clinicians must be more aware of the need to examine the eyes of extremely ill and sedated patients, such as those in intensive care units. Identifying the primary source of infection also requires a thorough examination.

In addition to initial diagnostic laboratory tests, testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection should be considered in otherwise healthy persons with endophthalmitis. Routine radiographs may reveal a primary pulmonary infection. Echocardiography is also warranted to assess the possibility of endocarditis.

Other tests may be necessary, depending on the clinical presentation. Blood cultures and intraocular cultures obtained from both chambers before institution of antibiotic therapy give the highest yield for isolating the pathogen. The use of blood culture bottles for the inoculation of ocular specimens may increase the yield.11 Cultures of other sites, including the catheter tip, should be obtained when appropriate. Gram stains of intraocular fluid may not be reliable. Immunologic tests for specific bacterial antigens can be performed in patients who have already received antibiotics; however, the usefulness of these tests has been challenged.12

Treatment

Prompt administration of antibiotic therapy is key in the acute management of endogenous endophthalmitis. This condition is particularly responsive to intravenous antibiotics, while in exogenous endophthalmitis, antibiotics are not actually necessary.13 Systemic antibiotics also treat distant foci of infection and prevent continued bacteremia, thereby reducing chances of invasion of the unaffected eye. Empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy with vancomycin (Vancocin) and an aminoglycoside or a third-generation cephalosporin is warranted.

Third-generation cephalosporins penetrate ocular tissues and are effective against gram-negative organisms. The nature of the clinical presentation, as well as the presumed (or confirmed) source of infection, can be used to guide the decision about which antibiotic to use. In cases of documented gastrointestinal or genitourinary infection, second- or third-generation cephalosporins and aminoglycosides are considered the drugs of choice. Vancomycin should be given to patients known to abuse drugs, covering the possibility of infection with Bacillus. In the presence of wounds, oxacillin or a first-generation cephalosporin should be used. If the patient's history, stains or culture results suggest a fungal infection, amphotericin B (Amphotec), fluconazole (Diflucan) or itraconazole (Sporanox) should be included in the regimen.

Intravitreal antibiotic injections have revolutionized the treatment of exogenous endophthalmitis, but their usefulness in endogenous cases is controversial. Similarly, surgical intervention (i.e., vitrectomy) is widely accepted in postsurgical and post-traumatic endophthalmitis, but its benefits in endogenous endophthalmitis have been debated.3,8

Surgical intervention is generally recommended for patients infected with especially virulent organisms, visual acuity of 20/400 or less, or severe vitreous involvement. The outcome of posterior diffuse endophthalmitis or panophthalmitis is frequently blindness, regardless of treatment measures. Vitrectomy and intravitreal antibiotics may, however, prevent ocular atrophy or the necessity for enucleation.

Some damage may also be related to inflammatory mediators. Steroids such as dexamethasone have been administered intravitreally, although their role is not clear. Topical steroids have been used empirically in patients with anterior focal or diffuse disease to prevent complications such as glaucoma and formation of synechiae.

The outcome of endogenous endophthalmitis (compared with that of exogenous endophthalmitis) is disappointing. The three main factors that result in a poor prognosis include more virulent organisms, compromised host conditions and delay in diagnosis. Even with aggressive treatment, in only about 40 percent of patients is vision preserved (i.e., ability to count fingers or better).

REFERENCES

1. Okada AA, Johnson RP, Liles WC, D'Amico DJ, Baker AS. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. Report of a ten-year retrospective study. Ophthalmology 1994;101:832-8.

2. Pflugfelder SC, Flynn HW Jr. Infectious endophthalmitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1992;6:859-73.

3. Greenwald MJ, Wohl LG, Sell CH. Metastatic bacterial endophthalmitis: a contemporary reappraisal. Surv Ophthalmol 1986;31:81-101.

4. Davis JL, Nussenblatt RB, Bachman DM, Chan CC, Palestine AG. Endogenous bacterial retinitis in AIDS. Am J Ophthalmol 1989;107:613-23.

5. Robbins JB, Schneerson R, Anderson P, Smith DH. The 1996 Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards. Prevention of systemic infections, especially meningitis, caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b. Impact on public health and implications for other polysaccharide-based vaccines. JAMA 1996;276: 1181-5.

6. Margo CE, Mames RN, Guy JR. Endogenous Klebsiella endophthalmitis. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Ophthalmology 1994;101: 1298-301.

7. Tseng CY, Liu PY, Shi ZY, Lau YJ, Hu BS, Shyr JM, et al. Endogenous endophthalmitis due to Escherichia coli: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 1996;22:1107-8.

8. Brod RD, Flynn HW Jr. Endophthalmitis: current approaches to diagnosis and therapy. Curr Opin Infect Dis 1993;6:628-37.

9. Fraser VJ, Jones M, Dunkel J, Storfer S, Medoff G, Dunagan WC. Candidemia in a tertiary care hospital: epidemiology, risk factors, and predictors of mortality. Clin Infect Dis 1992;15:414-21.

10. Rowsey JJ, Jensen H, Sexton DJ. Clinical diagnosis of endophthalmitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1987;27:82-8.

11. Joondeph BC, Flynn HW Jr, Miller D, Joondeph HC. A new culture method for infectious endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1989;107:1334-7.

12. Perkins MD, Mirrett S, Reller LB. Rapid bacterial antigen detection is not clinically useful. J Clin Microbiol 1995;33:1486-91.

13. Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study Group. Results of the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. A randomized trial of immediate vitrectomy and of intravenous antibiotics for the treatment of postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;113:1479- 96.

The Authors

CESAR F. ROMERO, M.D., is currently in private practice in Hamilton, Ala. He received a medical degree from the University of the Philippines in Manila and completed a residency in internal medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland.

MANDEEP K. RAI, M.D., is currently a staff physician at the Arizona Medical Clinic, Peoria, Ariz. Dr. Rai graduated from Christian Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana, India. She completed a residency in internal medicine at the State University of New York at Buffalo School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, and a fellowship in infectious disease at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

CAREEN Y. LOWDER, M.D., PH.D., is a staff member in the Division of Ophthalmology at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Dr. Lowder graduated from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, where she also received a doctorate in microbiology. Dr. Lowder completed a residency in ophthalmology at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation and a fellowship in uveitis at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine.

KARIM A. ADAL, M.D., M.S., is a staff member in the Department of Infectious Disease at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. He graduated from Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, and completed a residency in internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Dr. Adal also completed a fellowship in infectious disease and earned a master's degree in epidemiology at the University of Virginia School of Medicine Health Sciences Center, Charlottesville.

Address correspondence to Karim A. Adal, M.D., M.S., Department of Infectious Disease, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, 9500 Euclid Ave. (S32), Cleveland, OH 44195. Reprints are not available from the authors.

COPYRIGHT 1999 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group