Ever since the days when snake oil salesmen criss-crossed the American frontier peddling miracle potions, unwitting consumers searching for a magic bullet have eagerly spent hard-earned cash on unproven drugs and useless concoctions.

During the early 1900s, many believed that "William Radam's Microbe Killer," which was 99 percent water, would cure all diseases. In the 1950s, hundreds of men and women suffering from various types of cancer turned to a horse-blood extract as the cure. And, most recently, thousands of young professionals have begun using so-called "smart" drugs and "smart" drinks as a way to increase energy, improve memory, and boost intelligence.

Some "smart" drugs are prescription medications approved to treat debilitating mental disorders, such as dementia and Parkinson' s disease. Among the more popular are Hydergine (ergoloid mesylates), Eldepryl (selegiline ride), Dilantin (phenytoin), and Diapid (vasopressin).

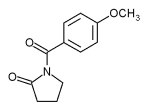

Other "smart" drugs are medications not approved in the United States. These include piracetam (Nootropil), aniracetam (Draganon), fipexide (Attentil), vinpocetine (Cavinton), and Oxicebral (vincamine).

"Smart" drinks are made with amino acids such as phenylalanine, choline, mudfine, and L-cysteine, which are blended into juices and other nonalcoholic beverages.

But, like cure-alls of the past, no scientific evidence exists to show that "smart" drugs and "smart" drinks work, and FDA has not approved any drug or product to enhance memory or intelligence.

"The notion that 'smart' drugs affect intellect is based on the belief that drugs designed to treat people suffering from dementia and other conditions that affect the mind can make normal people sharper," said Thomas Crook, Ph.D., a researcher with Memory Assessment Clinics, Inc., of Bethesda, Md. "But there is not scientific proof to back up this theory."

Crook, who headed the National Institute of Mental Health's geriatric psychopharmacology program from 1971 to 1985, said that no human studies objectively show that "smart" drugs can enhance the mental performance of normal individuals. No credible studies measuring subtle changes in normal individuals after taking "smart" drugs for a long period have been conducted.

"The research data I've seen was not based on well-controlled studies in which a 'smart' drug and a placebo were compared, and in which there was an objective measure of how successful the drug was, such as having to remember someone's name," Crook said.

"The clinical evidence relied on animal models, but animals and humans may not react the same. Individual people are different, too. A 25-year-old stockbroker won't react to certain stimuli in the same way that an older person would."

Safety Concerns

While efficacy of "smart" drugs is unproven, side effects associated with their use are well documented. Piracetam and Hydergine can cause insomnia, nausea and other gastrointestinal distress, and headaches.

Adverse reactions associated with Diapid include runny nose, nasal ulceration, abdominal cramps, and increased bowel movements.

Vincamine should not be used by pregnant women or children because it can cause gastrointestinal distress.

Although most of the known side effects are short-term, health professionals fear that the possibility of long-term side effects also exists.

"We just don't know what adverse effects there could be later," said James L. McGaugh, Ph.D., director of the Center for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, University of California-Irvine. "There haven't been enough studies conducted over a long period of time."

Further complicating the safety issue is the megadoses and different combinations of "smart" drugs users claim are needed to achieve the desired effects.

The effect of piracetam, according to "smart" drug enthusiasts, can be increased if taken in combination with Hydergine. Aniracetam, they say, works best if taken with choline. And no combination will work, say "small" drug users, unless taken over an extended period.

"Based on theoretical evidence, you'd have to keep taking them to maintain the effect," said Crook. "When taken in combination over time, we don't know that they're safe."

"Smart" drinks, while consisting of amino acids, present similar safety concerns. If the drink contains a large dose of a substance or if many drinks are consumed, toxicity and short-term adverse side effects are possible, although small doses may also be toxic.

A recent report on amino acids prepared by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology concluded that even healthy men who take single or incomplete mixtures of amino acids as dietary supplements are engaging in a potentially harmful practice. According to the report, other groups taking these supplements are at an even greater risk of possible adverse effects and should not use them without responsible medical supervision.

In large doses, phenylalanine may make some people irritable or cause insomnia.

In addition, this amino acid should be avoided by people with phenylketonuria (PKU), a birth defect caused by the body's inability to metabolize phenylalanine. (Diet products made with aspartame [NutraSweet] contain phenylalanine at low, safe levels for people who don't have PKU and must bear labels warning people with PKU of the presence of this amino acid.)

Too much dietary choline can cause gastroenteritis and pancreatitis.

L-cysteine should not be used by children or pregnant women because it could possibly harm the fetus, and published studies show that murine causes adverse effects in PKU patients, individuals with Wilson's disease--a potentially fatal genetic disorder caused by the body's inability to metabolize dietary copper--and persons taking MAO (monoarmne oxidase) inhibitors, such as the antidepressants Pareate, Nardil, Marplan, and Eutonyl.

Despite these known side effects, the "smart" drink faithful insist there is no danger.

"I don't believe the drinks have anything in them that will give me Alzheimer's when I'm 50," said Michelle Barnett, a 28-year-old San Francisco marketing specialist who has been consuming "smart" drinks for a year and a half. "The traffic outside my window is worse. The water is bad, and our food chain is bad. I think that if I drink amino acids it's positive, not negative."

McGaugh disagrees. "You can view these things as mind toys," McGaugh said. "People have responded to unsubstantiated claims."

The Rise in "Smart" Drug Use

"Smart" drugs began to gain popularity in the early '80s, when baby boomers in their 30s and 40s started using them as a way to improve job performance and gain an edge in the workplace.

There is no way to accurately calculate the number of people using "smart" drugs today, but Ward Dean, M.D., coauthor of Smart Drugs & Nutrients, the guide for users, estimated that the number is close to 100,000. "Smart" drink users, Dean said, number about 10,000, with many occasionally using "smart" drugs.

Another group of "smart" chug users is made up of healthy elderly persons who, even though they may not have age-associated memory impairment, feel they aren't as mentally sharp as they used to be, Dean said.

People with documented intellect impairments caused by Alzheimer's disease and stroke form the smallest population of "smart" drug users.

According to Dean, "smart" drugs cost about 85 cents a day to use. "Smart" drinks, served mostly in trendy California and New York bars, cost about $3 each.

Are "Smart" Drinks and Drugs Legal?

Because "smart" drinks are made with amino acids, which FDA regulates as foods, they are legal as long as they're not labeled with health claims. Under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, any product that makes medical claims is considered a drug and must be proven safe and effective. (Under the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990, certain health claims are permitted on foods; however, there is no approved health claim applicable to "Smart" drinks.)

Laws affecting "smart" drugs are less complicated. The promotion or sale of drugs for purposes not approved in the United States is illegal.

Unapproved medications used as "smart" drugs typically make their way into the United States through an abuse of FDA's "personal use" import policy.

FDA permits individuals to bring into this country small amounts of drugs for "personal use" when the drugs are sold in foreign countries but not in the United States. However, the drugs must not pose any unreasonable health risks, and must be used to treat a serious condition for which there is no approved treatment here. Permissible personal-use quantities generally do not exceed a three-month supply.

But some individuals have illegally used the "personal use" import policy for commercial gain.

"Once they have the 'smart' drugs in this country, some sell and distribute them for unapproved purposes," said Phillip L.B. Halpern, assistant U.S. attorney, Office of the U.S. Attorney, Southern Distnct of California, San Diego.

More Research Needed

While not endorsing the illegal use of drags, some health professionals believe that more research into the efficacy of "smart" drugs should be conducted. Thomas N. Chase, M.D., chief of the Experimental Therapeutics Branch of the National Institutes of Health, said that "smart" drugs need to be looked at more carefully.

"We should take some of these claims seriously enough to evaluate them. Some people feel that there is a conspiracy on the part of the federal government and FDA to withhold certain drugs. This drives them into the hands of entrepreneurs that make promises."

"We're early into this thing," said a 40-year-old writer, who takes a combination of piracetam, Hydergine, L-deprenyl, vincamine, and assorted vitamins. "In ten years, everybody over 35 is going to stop and ask themselves the question, 'Do I want to continue getting old? Do I want my brain to age?'"

And what about the side effects ? "There could be long-term side effects," said the writer, who says he's taken "smart" drugs since 1983, "but you would think that after so many years of people taking them some would have popped up."

Looking at "smart" drugs in such simplistic terms, however, can do more harm than good, said Crook. "You're dealing with balance systems in the brain. Any drug that has the ability to enhance cognition can also impair it."

McGaugh went a step further, warning that no one should spend money for a drug that has not been proven safe or effective.

"People are buying hope," McGaugh said. "They are skeptical about scientific claims and they say, 'you guys [the medical community] don't know.' But there simply isn't enough evidence."

FDA maintains that because "smart" drugs have not been subjected to adequate animal and human testing in controlled clinical trials, and have not been proven effective or their toxicity defined, they could be harmful. Strategies for regulating dietary supplements, including amino acids and other nutrients, are currently being evaluated by an FDA task force.

FDA is also working closely with state attorneys general and other state authorities to prevent the illegal sale and distribution of "smart" drugs.

Victor Lambert is a staffwriter for FDA Consumer.

COPYRIGHT 1993 U.S. Government Printing Office

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group