A mini-laboratory to help developing countries detect counterfeit and substandard medicines has been developed by the German Pharma Health Fund (GPHF), a charity organization established by the research-based pharmaceutical industry in Germany. The GPHF-Minilab(R) provides a reliable, simple, and inexpensive method for easily detecting adulterated drugs and is of special interest to hospitals and other health facilities, which are constantly at risk of having their supply chain infiltrated by pharmaceuticals of dubious quality.

Key Words: Counterfeit medicines; German Pharma. Health Fund; GPHF-Minilab

INTRODUCTION

THE WIDESPREAD DANGER of trade in counterfeit medicines has become a serious health problem throughout the world. People living in developing countries are most hard hit by counterfeit medicines. Doctors in developing countries are frequently unaware that failures in therapy may be due to the use of fake or substandard drugs, rather than an incorrect diagnosis or drug-resistant organisms.

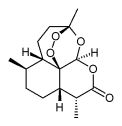

No one really knows, however, the scale of the problem, shrouded as it is in ignorance, confusion, and denial. The figures generally in use come from the World Health Organization (WHO), which estimates that as much as 10% of all branded medicine is counterfeit; this rises to 50% to 70% in some African countries. Sixty percent of counterfeit medicines detected by the WHO contained no active ingredient, 17% had the wrong amount of the active ingredient, and 7% were perfect copies of the real medicine (Figure 1). One third of all cases involved counterfeit antibiotics. The losses on legitimate sales have been valued at $20 billion a year, representing 7% of worldwide pharmaceutical sales.

"Fighting this global problem puts an additional burden on health systems that are often already over-stretched," commented Dr. Yasuhiro Suzuki, WHO executive director in charge of health technology and pharmaceuticals. "No country is immune from the threat of counterfeit drugs but those with weakly regulated pharmaceutical markets suffer most." Shortly after this statement at the 2000 World Health Assembly in Geneva, dozens of people died in Cambodia after taking counterfeit antimalarials. The victims included the head of Cambodia's wildlife protection office in the town of Siem Reap, who fell into a coma and died six days after unknowingly taking counterfeit medicine that was marketed as the powerful antimalarial drug mefloquine. From the outside, the counterfeit medicine looked exactly the same as the genuine product, and included a perfect copy of the security label's hologram. The inside, however, contained nothing but compressed flowers. The price was ridiculously low, $7 for 100 tablets. The officer ignored this early warning indicator that the product was fake and died.

The list of these incidents is long (1-25). In 1999, Hong Kong's police seized 340000 boxes of totally ineffective counterfeit emergency medication for stroke victims. In 1998, Brazil's daily newspapers published a list of 60 phony drug products warning doctors, pharmacists, and the general public to take a closer look at what they were prescribing, dispensing, or swallowing. In 1997, during an increase in malaria cases in the Kenyan highlands, stock of the genuine antimalarial sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine was used up due to panic buying, and completely ineffective fake antimalarials infiltrated the slums of Nairobi. In 1996, 90 Haitian children died of acute renal failure after taking an antifever syrup consisting mainly of toxic antifreeze intended for motor cars. In 1995, Medicins Sans Frontiers discovered false vaccines against meningitis circulating in Niger, where some 60000 people had been vaccinated with water.

THE GPHF-MINILAB

Owing to the widespread danger of counterfeit medicines, quality control in the distribution system of developing countries has acquired new dimensions today. If adherence to Good Manufacturing Practice cannot be assumed, more samples must be tested in order to maintain an appropriate assurance of drug quality. At the same time, however, pharmacopoeial analyses have become increasingly expensive and only a few centers of excellence in some countries are currently available to perform them. The development and use of simple tests should, therefore, facilitate a balance between the need to increase the extent of drug testing on the one hand, and the need to contain costs on the other.

GPHF, a charity organization established by the research-based pharmaceutical industry in Germany, set out to develop and supply a portable, tropics-compatible and easy-touse mini-laboratory which could verify the drug's content and thus, detect fake medicines by employing inexpensive analytical techniques. The intention was also to provide a simple drug quality control kit as a `first aid' measure for countries where the means for an effective drug quality-control system are not yet fully in place. Testing the quality of drugs by means of the GPHF-Minilab involves a four-stage test plan that employs very simple physical and chemical analytical techniques:

* A visual inspection scheme of solid dosage forms, including associated packaging material, for an early rejection of the more crudely presented counterfeits,

* A simple tablet and capsule disintegration test for a preliminary assessment of deficiencies related to drug solubility and availability,

* Simplified color reactions for a quick check of any drug present, thus, ensuring the drug's identity, and

* Easy-to-use thin layer chromatographic assays for a quick check of quantities of drug present, thus, ensuring the drug's potency.

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) has been introduced into the Minilab test scheme in order to obtain confirmation of whether the amount of drug stated on the label is actually in the product. The results obtained by a simple visual inspection of the chromatoplates produced can be as accurate as 10% if great care is taken and analytical skill executed. Very experienced staff can do even better. In order to achieve this accuracy training of staff might be required before using the Minilab's procedures for the first time.

In practice, people are asked to produce a higher (100%) and lower (80%) standard solution from authentic secondary reference standards supplied alongside the Minilab equipment. These are the specification limits of TLC when products with a drug content of 90% are allowed to pass the test (90% +/- 10% allowances for assay sensitivity). The principal spot obtained with the test solution must correspond in terms of color, shape, size, intensity, and travel distance to that in the chromatographic runs obtained with the lower and higher standard solution. If the spot's intensity is lower, the product is underdosed, if it is higher, the product is overdosed. If there is no spot at all, the product is most likely a counterfeit. If the travel distance of the reference spots is not matched then the product contains the wrong active ingredient. Overall, TLC appears to be a good and inexpensive analytical method to verify the product's drug content and identity. Identification is double checked by using color reactions.

Products currently covered by the project are: acetylsalicylic acid, aminophylline, amoxicillin, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, chloroquine, cloxacillin, cotrimoxazole, erythromycin, furosemide, isoniazid, mebendazole, metamizole, metronidazole, paracetamol, phenoxymethylpenicillin, prednisolone, rifampicin, sulfadoxine combined with pyrimethamine, and tetracycline. Publication of 10 more monographs on artesunate, cefalexin, ciproflaxacin, ethambutol, glibenclamide, griseofulvin, mefloquine, pyrazinamide, quinine, and salbutamol is pending.

All development work has been carried out in close cooperation with the School of Pharmacy at the University of Bonn and the Department of Tropical Medicine at the Medical Mission Institute in WUrzburg, Germany. The overall priority during the development phase was to devise reliable test methods employing a simple and versatile technology. Each laboratory comes with manuals documenting sample preparation and assay results on each individual compound by color photographs including, in the case of TLC, relative retention factors obtained during feasibility studies performed in Kenya, Tanzania, Ghana, and the Philippines between 1997 and 1998.

These studies have also shown that the GPHF-Minilab is a practical and effective tool for the verification and quality assurance of pharmaceuticals used in hospitals and other health facilities in the developing world. However, no regulatory action should be initiated on the basis of their results. All samples considered to be potentially counterfeit or substandard would need to be referred for testing according to the pharmacopoeial, compendial, or legally accepted reference methods) to validate the findings of the initial screenings. Until then, batches under scrutiny stay in quarantine or, preferentially, are just not accepted from a pending offer.

Since the successful field testing was completed, more than 50 GPHF-Minilabs have been shipped to other health projects operating in West and East Africa (Cameroon, Congo, Guinea, Ghana, Gabun, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, Sudan, Tanzania, Zimbabwe), the Caribbean (Saint Lucia), South America (Guyana), Asia (India, Nepal, Philippines, Sri Lanka), and the Middle East (Palestine). Frequently, feedback is difficult to obtain as the real stakeholders in the inhumane business of drug counterfeiting are not known and discussing the truth in public might be detrimental to career and even life. Feedback obtained so far from the African region showed that 19 of 141 samples checked with three Minilabs in the year 2000 were of substandard quality and that a further 4 were fakes. It is hoped that more comprehensive results will be obtained in the future from ongoing long-term observation studies carried out together with local project champions in that region.

Currently, the GPHF-Minilab supports the Roll Back Malaria Programme of the World Health Organization (WHO) in sub-Saharan Africa where it is used as a simple screening method for the rapid detection of counterfeit and substandard antimalarials. All practical experience so far has confirmed that the procedures employed can be performed without problems in primary health care stations, hospitals, and pharmacies, even those that are based in rural areas.

Other major project champions are the Committee of German Doctors for Developing Countries, the German Medical Aid Organization action medeor, the Infusion Units Project of the Protestant Lutheran Church of Tanzania, and the Diocesan Pharmacies of the National Catholic Secretariat in Ghana. Here, the GPHFMinilab(R) has proven that it can play a key role in keeping the costs of drug quality screening as low as possible for government authorities, professional bodies, and nongovernmental organizations engaged in primary health care. "The Minilab is helping us a lot," said Charles Allotey, the head pharmacist from the Catholic Drug Centre in Ghana. "We are able to check the quality of a product before buying it and all our beneficiaries feel protected buying from us."

The GPHF-Minilab has been awarded EXPO 2000 Project All Over The World status. As such, the initiative of the German Pharma Health Fund demonstrates in an exemplary way that the practical implementation of Agenda 21 is possible.

The quantities of reagents and solvents supplied in the start-up package are sufficient to support at least 3000 color reactions in order to verify the drug's identity and 1000 TLC runs in order to verify their potency, putting the average cost per test at approximately $1.50. All analytical reagents and equipment were carefully selected so that they are likely to be available in developing countries.

SUMMARY

Employing GPHF-Minilabs, an anti-counterfeit kit assembled into two cases, protects people from taking fake medicines detrimental to human life. The Minilabs reduce the workload of central drug control laboratories and can play a key role in keeping the costs of drug analyses in developing countries as low as possible. Establishing them as an early alert system out in the field will enable health authorities and other health care providers to tackle the widespread danger of trade in counterfeit medicines in a very efficient manner. More information is available at the German Pharma Health Fund's Web site (www. gphf.org).

REFERENCES

1. Fake malaria drugs in Tanzania. Pharma Market-- letter. February 26, 2001.

2. Sawdust in the ointment. (German language only). Der Spiegel, No. 51, December 2000.

3. New task force set up to track drug pirating. Shanghai Daily, November 22, 2000.

4. Experts warn of fakes in Russia pharmaceuticals market. TASS News Agency, October 17, 2000.

5. Pharmacy matters in Kenya: Up to 18% of drugs circulating in the market are of poor quality. Africa Health, No. 48, September 2000.

6. Malaria: Dozens dead in Cambodia from counterfeit drugs. United Nations Foundation UN Wire, May 30, 2000. www.unfoundation.org/unwire/archives.

7. Antibiotic imports may have killed 17. USA Today, May 8, 2000.

8. Illegal medicines recovered near Durban. Health News Daily, Johannesburg, April 20, 2000.

9. Crackdown on illegal medicine sales in China. Pharma Marketletter, January 3, 2000.

10. Crackdown on illegal sales of medicine in Benin. WHO Essential Drug Monitor, No. 27. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; December 1999.

11. Fake drugs swamp Malawi. Africa Health, No. 38, November 1999.

12. Reversing the health decline in Nigeria. Scrip, No. 2474, September 22, 1999.

13. Counterfeit stroke medication sold over border. The South China Morning Post, July 9, 1999.

14. Brazil steps up war on counterfeits. Scrip, No. 2346, June 24, 1999.

15. Fake medicines sold in Tajikistan pharmacies. Pharma Marketletter, June 14, 1999.

16. Black market in medicine thrives in state. The Times of India, May 14, 1999.

17. Challenging the counterfeiters. Scrip Magazine, Febmary 1999.

18. Counterfeit and substandard drugs in Myanmar and Viet Nam. Eshetu Wondemagegnehu, EDM Research

Series, No. 29, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1999.

19. Guidelines for the development of measures to combat counterfeit drugs. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, Department of Essential Drugs and Other Medicines; 1999.

20. Glycerol contaminated with diethylene glycol. WHO Drug Information, Vol. 12, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; November 1998.

21. U.S. is faulted over screening for drug safety. The New York Times, May 3, 1998.

22. Export drugs seized. Sunday Nation, Nairobi, March 22, 1998.

23. Dangerous medicines on sale. Sunday Standard, Nairobi, November 9, 1997.

24. Basco LK, et al. False chloroquine resistance in Africa. Lancet. 1997;350:224.

25. Kron MA. Substandard primaquine phosphate for US Peace Corps personnel. Lancet. 1996;348:1453.

RICHARD W. O. JAHNKE AND GABRIELE KUSTERS

German Pharma Health Fund (GPHF), Frankfurt, Germany

KLAUS FLEISCHER

Medical Mission Institute, Wurzburg, Germany

Reprint address: Dr. Richard Jahnke, Project Manager, German Pharma Health Fund e.V. (GPHF), Postfach 150 123, 60061 Frankfurt, Germany. E-mail: info@ gphf.org.

Copyright Drug Information Association Jul-Sep 2001

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved