ABSTRACT This study was conducted to investigate the effect of dietary ascorbic acid (AA) on reproductive performance of shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Stay C-35 (a stable derivative, mainly monophosphate) was selected as AA source. Four grade levels of ascorbic acid equivalent (AAE) (0, 400, 800, and 1200 mg [kg.sup.-1] diet) were supplemented to the basal diet. Gonadosomatic index (GSI), hepatosomatic index (HSI), fecundity, and egg diameter were not significantly affected by supplemented AA levels (P > 0.05), although AA concentrations in hepatopancreas, ovaries, and eggs increased significantly with dietary AA levels (P < 0.05). Average daily spawns per female, hatching rate, and fertilization rate were also significantly affected by dietary AA levels (P < 0.05). Results of this study confirmed the importance of supplementation of AA to the basal diet and suggested that at least 800 mg AAE [kg.sup.-1] diet was needed to supplement to the basal diet to acquire excellent ovarian maturation and reproductive performance.

KEY WORDS: ascorbic acid, broodstock, Litopenaeus vannamei, reproductive performance

INTRODUCTION

Although nutrition has been identified as a key factor in the reproduction of broodstock shrimp, information on broodstock nutrition is still limited (Harrison 1990, Wouters et al. 2001b). Studies into the effect of nutrients on reproduction are essential to formulate high-quality broodstock diets as well as to elevate reproductive performance and quality of hatched nauplii.

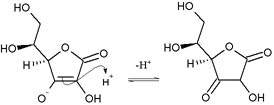

Dietary ascorbic acid (AA) is an essential nutrient for penaeid shrimp (He & Lawrence 1993). Available studies into the role of this vitamin have focused on its effect in immature stages and suggested a dietary source of AA is required to prevent deficiency symptoms, such as reduced growth, melanized lesions underneath the exoskeleton, poor wound repair, and high mortality (Hunter et al. 1979, He & Lawrence 1993, Magarelli et al. 1978, Shiau & Hsu 1994). The importance of AA in reproduction has also been reported in fish and shrimp. In addition to the role of AA as an antioxidant and an enzyme cofactor in the formation of collagen (Barnes & Kodicek 1972, Hunter et al. 1979), which may be especially important during embryonic and larval development, it is also involved in the regulation of biosynthesis of steroid hormones (Hilton et al. 1979, Levine & Morita 1985, Seymour 1981). The essentiality of AA for fish broodstock was well established (Lavens et al. 1999a, Mangor-Jensen & Holm 1994, Sandnes et al. 1984, Soliman et al. 1986, Waagbo et al. 1989), and the importance of AA in shrimp reproduction has also been confirmed. Alava et al. (1993a, 1993b) reported AA-deficient diet retarded gonadal maturation of Marsupenaeus japonicus. Cahu et al. (1995) found AA levels in Farfantepenaeus indicus eggs were affected by dietary vitamin levels, and high hatching rate of F. indicus eggs were related to high AA levels in the eggs. Wouters et al. (2001a) detected a sharp decrease of AA content in spent ovaries and nauplii of Litopenaeus vannamei and suggested that AA was consumed during egg development and hatching.

Till now, there is still no information on the effect of dietary AA on ovary maturation and reproduction of L. vannamei. In a previous study, we successively substituted a natural diet consisting of 50% bloodworm (Glycera chirori) and 50% oyster (Crassostrea rivularis) with an artificial diet for broodstock L. vannamei. In the current study, we used this artificial diet as the basal diet and selected Stay C-35, a stable derivative, as AA source to investigate the effect of dietary AA on the reproductive performance of L. vannamei. The effect of dietary AA levels on AA concentrations in ovaries, hepatopancreas, and eggs was also detected.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Treatments

Domestic L. vannamei breeders were obtained from Dongfang Co. (Zhanjiang, China). They were kept in maturation tanks for 3 wk to acclimate experimental conditions and were fed the basal diet without any AA supplemented (Diet C1). A unisex system was used as described by Browdy et al. (1996): 4 tanks were stocked with 15 females each and 4 tanks with 15 males each. They were divided into four groups: Group C1-C4, which were subjected to Diet C1-C4, respectively. Each group consisted of a male tank and a female tank. After acclimation, female shrimps were unilaterally eyestalk-ablated with a pair of burned tweezers. To identify each female in the same group, part of its telson was cut, except five females were left intact and later sampled to test gonadosomatic index (GSI) and hepatosomatic index (HSI). The postablation phase of the experiment lasted for 50 days.

The maturation tanks were rectangular-shaped cement tanks (2 x 3 [m.sup.2], 55 cm water depth) in which sand-filtered and UV-treated seawater was exchanged at a rate of 200% daily. The physicochemical parameters of the water were average temperature, 28.5[degrees]C; average salinity, 30 mg [L.sup.-1]; photoperiod, 12 h light/ 12 h dark; and light intensity, 20 mW [m.sup.-2]. Under these conditions, oxygen remained close to saturation, 6.2 g [m.sup.-3], pH was 8.2 [+ or -] 0.1, while ammonia, nitrite, and nitrate levels remained almost the same as in the inlet water.

Diets and Feeding

In a previous study, the effect of 100% fresh food replacement with an artificial diet on ovarian maturation and spawning performance of broodstock L. vannamei was tested. Results showed that 100% artificial diet gave superior spawning performance to the fresh food control (consisting of 50% G. chirori and 50% C. rivularis), such as higher total spawn numbers (32 vs. 24), maturation ratio (90% vs. 70%), and daily spawns per female (0.091 vs. 0.069). As such, a fresh food replacement level of 100% was selected for the current study, and the same basal diet--with the following composition related to dry matter: protein 48.98%, lipid 11.57%, and ash 15.42%--was used in the experiment. Ingredients and composition of basal diet are shown in Table 1. Four grade levels of ascorbic acid equivalent (AAE) were added to the basal diet (Table 2). ROVIMIX STAY C-35 (mainly monophosphate, containing 350 g L-AA [kg.sup.-1]) was selected as the AA source for its excellent stability and bioavailability (Alexis et al. 1999). The diets were prepared in the following manner. All dried ingredients were smashed and sieved, mixed with 35% (w/w) water, and the resulting dough was pelleted with a meat grinder and dried at room temperature. Then the dried "spaghetti-like" 3-mm-diameter strands were crumbled to about 5-mm long and kept in sealed plastic bags at -20[degrees]C until use. Shrimps were fed 4 times daily (0800, 1100, 1400, and 1800 local time) with a measured ratio of 6% of the tank biomass (wet weight). Uneaten food was collected daily.

Broodstock Maturation and Spawning

After unilateral ablation, the females were visually examined for ovarian maturation stages at time 2000 every night according to Wouters et al. (2001a). For the females with intact telsons, when the ovary of the first female developed to stage VI, they were weighed and dissected, while keeping them on ice, to determine the gonadosomatic index (GSI = 100 x gonad weight/total body weight) and hepatosomatic index (HSI = 100 x hepatopancreas weight/total body weight).

The remained females ready to spawn were transferred to the corresponding male tanks to mate. Mature females with an attached spermatophore were placed in individual 120-L spawning tanks and after spawning were returned to their own maturation tanks. Fecundity (number of eggs per spawn) was estimated by stirring the spawning tanks and counting three subsamples of 50-mL each. Fertilization rate was assessed in three 50-mL samples of each spawn, based on the presence of a double membrane in the eggs. A sample of 10,000 eggs was incubated at 29[degrees]C for estimating the hatching rate (% nauplii/fertilized eggs). All spawns were hatched individually. Hatching rate was calculated by counting the number of nauplii per spawn after positive phototropism selection. Egg diameter was estimated with a light microscope and a micrometer. About 80 mg eggs were sieved from each spawn and immediately rinsed in freshwater and stored at -70[degrees]C. Egg samples from the same group were pooled to obtain sufficient eggs for AA analysis. At the end of the experiment, five females with ovaries of stage II from each group were dissected. Hepatopancreas and ovaries were pooled and stored at -70[degrees]C for latter AA analysis.

Biochemical Analysis

Triplicate biochemical analysis of the basal diet was conducted according to the following standard procedures (AOAC 1990). Moisture was determined by oven drying to constant weight at 105[degrees]C. Crude protein (N x 6.25) was derived from Kjeldahl nitrogen analysis. Ash was determined at the residue after muffle furnace ignition at 550[degrees]C for 6 h. Total lipid content was determined by Soxhlet extraction with petroleum ether at 60[degrees]C for 8 h.

Tissue AA determinations were conducted by HPLC (HP1100) according to Alava et al. (1993b) and modified slightly. The analytical condition of HPLC was as follows: detection at UV-240 nm; column temperature, 30[degrees]C; eluent, 0.1 M K[H.sub.2]P[O.sub.4] + 0.5% metaphosphotic acid w/v, pH 3.4; flow speed, 0.8 mL/min. AA was extracted from samples by the method of Nelis et al. (1997). Freeze-dried samples of 0.5 g were suspended in the extractant of 1% acetic acid-0.1% metaphosphotic acid-1 mM EDTA and ultrasonically homogenized for 10 min in an ice bath. The mixture was centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000g and passed through a 0.45-[micro]m cellulose acetate membrane filter (SIGMA). Ten microliters of filtrate was introduced in the HPLC injection port. AA (Biochemika ultra, SIGMA) was used as standard.

Statistical Analyses

Each female in the same group was considered as an experimental unit for replication. Data of GSI, HSI, fecundity, daily spawns per female, egg diameter, fertilization rate, and hatching rate from each group were subjected to one-way ANOVA and subsequent Duncan's multiple-range test to determine difference in means. Prior to analysis, Levene's test for homogeneity of variances was used to verify the assumptions for further analysis. There was no need to transform data. A regression analysis was used to determine the relationship between fecundity, egg diameter, fertilization rate, and hatching rate and spawn order. No correlations were detected between them, and spawn order was not considered as an additional factor to evaluate. An alpha level for all tests was set at 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using Systat package (SYSTAT, 1996).

RESULTS

Average initial weight of female and male shrimps was 49.44 [+ or -] 4.29 g and 48.04 [+ or -] 4.81 g, respectively. As slightly mortality, probably induced by manipulation, occurred in some groups after 30 days, number of spawns was calculated per female per day.

Reproductive performance of different groups is shown in Table 3. Results showed that GSI increased with the increasing levels of AA, but the difference was not significant (P > 0.05). HSI values of female shrimps were also not significantly affected by dietary AA levels, though the HSI values of groups C2, C3, and C4 were slightly higher than that of group C1. Average daily spawns per female increased significantly with the AA levels (P < 0.05), and females of group C3 had the highest daily spawns, which was significantly higher than that of group C1 (0.074 vs. 0.050). Fecundity of all the females was similar, and there was no significant difference between the groups (P > 0.05). Similarly, egg diameter was almost the same and seemed not to be affected by dietary AA levels. Supplementation of AA to the basal diet increased the fertilization rate and hatching rate significantly (P < 0.05). Fertilization rate of group C2 (62.58%) was significantly higher than that of group C1 (53.76%) whereas group C3 had the highest fertilization rate (71.70%), which was significantly higher than those of groups C2 and C1. Hatching rate of group C4 was highest (61.08%), but was not significantly different with group C3 (58.13%), and the hatching rate of groups C1 (37.88%) and C2 (47.58%) was significantly lower than those of groups C3 and C4.

AA content in hepatopancreas, ovaries, and eggs of female L. vannamei is shown in Table 4. These females were at maturity stage II, with mean GSI values of 1.54 [+ or -] 0.05 for group C1, 1.57 [+ or -] 0.05 for group C2, 1.63 [+ or -] 0.09 for group C3, and 1.60 [+ or -] 0.06 for group C4, respectively. Results showed that there were much higher concentrations of AA in ovaries than in eggs and hepatopancreas. Tissue AA content was significantly affected by dietary AA levels. There were 19.34 mg [kg.sup.-1] and 21.36 mg [kg.sup.-1] in the hepatopancreas of groups C1 and C2, which were significantly lower than those of groups C3 (37.13 mg [kg.sup.-1]) and C4 (40.79 mg [kg.sup.-1]). AA concentrations in ovaries and eggs increased significantly with the increasing AA levels (P < 0.05), and there was significant difference between the different groups.

DISCUSSION

The current study showed the importance of supplemental AA in broodstock diets of L. vannamei for enhanced ovarian maturation and reproduction. It appeared that AA concentration in the basal diet was sufficient to maintain normal survival, successive maturation, and spawns; however, for significantly higher daily spawns, fertilization rate, and hatching rate, supplementation of this vitamin to broodstock diet was necessary.

GSI and HSI indicated the effect of AA levels on the development of ovaries and hepatopancreas of female L. vannamei. GSI and HSI values of females fed the diet without AA supplementation were lower than those fed AA-supplemented diets, although the difference was not significant (P > 0.05). The period between eyestalk ablation and the first maturation of the females with intact telsons was only 5 days, and the relatively short period of time might account for the similar values of GSI and HSI. Females fed diets supplemented with 800 and 1200 mg [kg.sup.-1] AAE gave significantly higher daily spawns than those fed nonsupplemented diet. This result indicated that supplementation of at least 800 mg [kg.sup.-1] AAE to the basal diet was able to significantly enhance the ovarian maturation of female L. vannamei. Alava et al. (1993a, 1993b) also concluded the positive effect of AA on ovarian maturation of M. japonicus and suggested at least 500 mg [kg.sup.-1] AMP in the broodstock diet was necessary for ovarian maturation.

In this study, AA concentrations in hepatopancreas, ovaries, and eggs were widely affected by dietary AA levels. AA content in ovaries and eggs increased significantly with the increasing dietary AA levels. The similar trend has been confirmed in the studies on M. japonicus conducted by Alava et al. (1993b) and that on F. indicus by Cahu et al. (1995). There were higher levels of AA in ovaries than in hepatopancreas, as was shown in M. japonicus (Alava et al. 1993b), Palaemonetes pugio (Coglianese & Neff 1981), and Macrobrachium rosenbergii (Cavalli et al. 2001). The ovaries sampled in the current study were from females at maturation stage II, so the high levels of AA in pre-mature ovaries might be related to an increased requirement in the eggs as suggested by Hilton et al. (1979). Sandnes et al. (1984) and Soliman et al. (1986) showed that broodstock dietary AA was transferred to eggs where it was stored for use during embryogenesis and development of larvae until the first feed intake. The positive effect of AA in shrimp production might be associated with the general role as an antioxidant (Wouters et al. 1999) as well as its action in the hydroxylation of protein-bound proline and lysine, which provide stable triple helicoidal collagen through the embryonic stages (Barnes & Kodicek 1972). Guary et al. (1975) postulated that ovarian AA could be consumed during steroidogenesis, and the study of Calvalli et al. (2001) provided evidence for the possible demand for AA by the hydroxylating reactions in steroidogenesis in the ovarian follicle cells. Similarly, Wouters et al. (2001a) detected higher AA concentrations in immature, maturing, and mature ovaries than in ovaries of spent females and nauplii of L. vannamei, and suggested that the lost AA was used during egg development and hatching.

Results of the current study showed that supplementation of more than 800 mg [kg.sup.-1] AAE to the basal diet could significantly increase the fertilization rate and hatching tale of broodstock L. vannamei. Cahu et al. (1995) also suggested a positive relationship between improvement of egg hatchability and high AA concentration in broodstock diets as well as in eggs of F. indicus. The same positive effect of supplemented AA on egg quality and hatching rate was also observed in fish (Sandnes et al. 1984, Soliman et al. 1986), and the feeding of an AA-deficient diet to broodstock fish could diminish reproductive performance (Hilton et al. 1979).

A dietary source of AA is required by all species of shrimp tested to date (Conklin 1997), though a possible limited synthesis of AA was suggested in P. californiensis and L. stylirostris by Lightner et al. (1979). He & Lawrence (1993) indicated that dietary AA requirement of L. vannamei was size-dependent and decreased with increased size. They reported that minimum dietary AA levels required for normal survival were 120 mg [kg.sup.-1] and 41 mg [kg.sup.-1] diet for shrimp with an initial weight of 0.1 g and 0.5 g, respectively. Similarly, Lavens et al. (1999b) pointed out that for early postlarval L. vannamei, an optimal dietary AA level of 130 mg [kg.sup.-1] diet was needed to acquire best growth performance. However, for broodstock shrimp during ovarian maturation and reproduction, as the active synthesis of ovarian nutrients, egg yolk compounds, sex steroids, and embryo development will consume considerable amounts of AA, much higher levels of dietary AA should be required. This has been confirmed in the current study, which showed that supplementation of at least 800 mg [kg.sup.-1] AAE to the basal diet was needed to bring excellent ovarian maturation and reproductive performance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Mr. Chen Wenlin for kindly offering shrimp breeders and experimental facilities. We also thank Yuehai Feed Co. Ltd and Mr. Zheng Shixuan for offering feed ingredients and manufacturing facilities. Sincere thanks are also given to Mr. Cheng Kaimin and Mr. Zhou Qicun for their help in feed manufacturing. This work was funded by the Science Innovative Project (No KSCX2-1-04-04) from the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

LITERATURE CITED

Alava, V. R., A. Kanazawa, S. Teshima & S. Koshio. 1993a. Effects of dietary vitamins A, E and C on the ovarian development of Penaeus japonicus. Nippon Susian Gakkaishi 59:1235-1241.

Alava, V. R., A. Kanazawa, S. Teshima & S. Koshio. 1993b. Effect of dietary L-ascorbyl-2-phosphate magnesium on gonadal maturation of Penaeus japonicus. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 59:691-696.

Alexis, M. N., I. Nengas, E. Fountoulaki, E. Papoutsi, A. Andriopoulou, M. Koutsodimou & J. Gaubaudan. 1999. Tissue ascorbic acid levels in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) and gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata L.) fingerlings fed diets containing different forms of ascorbic acid. Aquaculutre 179:447-456.

AOAC. (Association of Official Analytical Chemists). 1990, Official Methods of Analysis. 15th ed. Arlington, VA: AOAC. p. 20,931.

Barnes, M. J. & E. Kodicek. 1972. Biological hydroxylations and ascorbic acid with special regard to collagen metabolism. Vitam. Horm. 30:1-43.

Browdy, C. L., K. McGovern-Hopkins, J. S. Hopkins, A. D. Stokes & P. A. Sandifer. 1996. Factors affecting the reproductive performance of the Atlantic white shrimp, Penaeus setiferus, in conventional and unisex tank systems. J. Appl. Aquacult. 6:11-25.

Cahu, C. L., G. Cuzon & P. Quazuguel. 1995. Effect of highly unsaturated fatty acids, [alpha]-tocopherol and ascorbic acid in broodstock diet on egg composition and development of Penaeus indicus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 112A:417-424.

Cavalli, R. O., M. Tamtin, P. Lavens, P. Sorgeloos, H. J. Nelis & A. P. De Leenheer. 2001. The content of ascorbic acid and tocopherol in the tissues and eggs of wild Macrobrachium rosenbergii during maturation. J. Shellfish Res. 20:939-943.

Coglianese, M. & J. M. Neff. 1981. Evaluation of the ascorbic acid status of two estuarine crustaceans: the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus and the grass shrimp, Palamonetes pugio. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 68A:451-455.

Conklin, D. E. 1997. Vitamins. In: L. R. D'Abramo, D. E. Conklin & D. M. Akiyama, editors. Crustacean nutrition. Baton Rouge, LA: World Aquaculture Society. pp. 123-149.

Guary, M. M., H. J. Ceccaldi & A. Kanazawa. 1975. Variations du taux d'acide ascorbique au cours du developpement de l'ovarie et du cycle d'intermue chez Palaemon serratus (Crustacea: Decapoda). Mar. Biol. 32:349-355.

Harrison, K. E. 1990. The role of nutrition in maturation, reproduction and embryonic development of decapod crustaceans: a review. J. Shellfish Res. 9:1-28.

He, H. & A. L. Lawrence. 1993. Vitamin C requirements of the shrimp Penaeus vannamei. Aquaculture 114:305-316.

Hilton, J. W., C. Y. Cho, R. C. Brown & S. S. Slinger. 1979. The synthesis, half-life and distribution of ascorbic acid in rainbow trout. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 63A:447-453.

Hunter, B., P. C. Magarelli, D. V. Lightner & L. B. Colvin. 1979. Ascorbic-dependent collagen formation in penaeid shrimp. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 64B:381-385.

Lavens, P., E. Lebegue, H. Jaunet, A. Brunel, Ph. Dhert & P. Sorgeloos. 1999a. Effect of dietary essential fatty acids and vitamins on egg quality in turbot broodstocks. Aquaculture International 7:225-240.

Lavens, P., G. Merchie, X. Ramos, A. L. Kujan, A. V. Hauwaert, A. Pedrazzoli, H. Nelis & A. De Leenheer. 1999b. Supplementation of ascorbic acid 2-monophosphate during the early postlarval stages of the shrimp Penaeus vannamei. Aquaculture Nutrition 5:205-209.

Levine, M. & K. Morita. 1985. Ascorbic acid in endocrine systems. Vitam. Horm. 42:1-64.

Lightner, D. V., B. Hunter, P. C. Magarelli, Jr. & L. B. Colvin. 1979. Ascorbic acid: nutritional requirement and role in wound repair in penaeid shrimp. Proc. World Maricult. Soc. 10:513-528.

Magarelli, P. C. & L. B. Colvin. 1978. Depletion/repletion dynamics of ascorbic acid in two species of penaeid: Penaeus californiensis and Penaeus stylirostris. Proc. World Aquacult. Soc. 9:235-241.

Mangor-Jensen, A. & J. C. Holm. 1994. Effects of dietary vitamin C on maturation and egg quality of cod Gadus morhua L. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 25:30-40.

Nelis, H. J., A. P. De Leenheer, G. Merchie, P. Lavens & P. Sorgeloos. 1997. Liquid chromatographic determination of vitamin C in aquatic organisms. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 35:337-341.

Sandnes, K., Y. Ulgenes, O. R. Braekkan & F. Utne. 1984. The effect of ascorbic acid supplementation in broodstock feed for reproduction of rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri). Aquaculture 43:167-177.

Seymour, E. A. 1981. Gonadal ascorbic acid and changes in level with ovarian development in the crucian carp, Carassius carassius (L.). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 70A:451-453.

Shiau, S. Y. & T. S. Hsu. 1994. Vitamin C requirement of grass shrimp, Penaeus monodon, as determined with L-ascorbyl-2-monophosphate. Aquaculture 122:347-357.

Soliman, A. K., K. Jauncey & R. J. Roberts. 1986. The effect of dietary ascorbic acid supplementation on hatchability, survival rate and fry performance in Oreochromis mossambicus (Peters). Aquaculture 59: 197-208.

Waagbo, R., T. Thorsen & K. Sandnes. 1989. Role of dietary ascorbic acid in vitellogenesis in rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri). Aquaculture 80: 301-314.

Wouters, R., L. Gomez, P. Lavens & J. Calderon. 1999. Feeding enriched Artemia biomass to Penaeus vannamei broodstock: its effect on reproductive performance and larval quality. J. Shellfish Res. 18:651-656.

Wouters, R., C. Molina, P. Lavens & J. Calderon. 2001a. Lipid composition and vitamin content of wild female Litopenaeus vannamei in different stages of sexual maturation. Aquaculture 198:307-323.

Wouters R., P. Lavens, J. Nieto & P. Sorgeloos. 2001b. Penaeid shrimp broodstock nutrition: an updated review on research and development. Aquaculture. 202:1-21.bb

SHAOBO DU, CHAOQUN HU AND QI SHEN

Laboratory of Applied Marine Biology, South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, The Chinese Academy of Sciences, 510301, Guangzhou, People's Republic of China

COPYRIGHT 2004 National Shellfisheries Association, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group