Examining ease studies from patients with interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) is important in order to evaluate current diagnosis and treatment options. Two eases will be discussed; the first ease examines a patient with usual interstitial pneumonia, and the second ease examines a patient with subacute ILD and elements to suggest a forme fruste presentation of an unclassifiable connective tissue disease. Each case highlights components of the differential diagnosis, as well as reviews the treatments and prognoses of these patients. The eases provide clinical pearls that are designed to enhance the reader's understanding of ILDs.

Key words: case study reviews; idiopathic interstitial pneumonia; interstitial lung disease; idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Abbreviations: ANA = antinuclear antibody; anti-Jo-1 = histidyl-t-RNA synthetase. DLCO = diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; HRCT = high-resolution CT; ILD = interstitial lung disease; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; NSIP = nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; RNP = ribonucleoprotein; SCL = scleroderma; SSA = anti-Ro antibody; SSB = anti-La antibody; TLC = total lung capacity; UIP = usual interstitial pneumonia

**********

CASE 1: 68-YEAR-OLD MAN WITH EXERTIONAL BREATHLESSNESS

A 68-year-old radiologist presented to the pulmonologist with worsening exertional breathlessness that had become more apparent over the preceding 3 to 6 months. He reported being fairly active, including exercising regularly at a local gym. If he were to run up a flight of stairs or walk fast, he would become significantly short of breath. He reported an intermittent nonproductive cough, which had developed over the preceding several months. He had no history of respiratory disease, and was a lifelong nonsmoker. He described poor ventilation in the radiology reading room, in which he has worked for the past 30 to 35 years, and he reported a concern that this exposure contributed to the development of some type of lung disease. On review of systems, the patient reported occasional arthralgias, which are worse in the morning. He denied Raynaud symptoms, has experienced significant gastroesophageal reflux disease, but denied aspiration.

Physical Examination

Auscultation of the lungs revealed a few fine late inspiratory crackles at both bases with no wheezes, rhonchi, or other adventitious sounds. Pulmonary function studies revealed a mild restrictive ventilatory defect with the following results: FE[V.sub.1], 75% predicted; FVC, 77% predicted; total lung capacity (TLC), 75%; and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO), 68% (uncorrected for alveolar volume). Oxygen saturation declined from 95 to 92% during a "modified" 6-min walk test that included five flights of stairs. Digital clubbing was absent.

Laboratory Findings

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 20 mm/h, the test for antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) was positive at a titer of 1:40, the rheumatoid factor level was normal, the tests for anti-Ro antibody (SSA) and anti-La antibody (SSB) were negative, the tests for ribonucleoprotein (RNP) and scleroderma (SCL)-70 antibodies were negative, the aldolase level was normal at 5.6 U/L, and the test for the histidyl-t-RNA synthetase (anti-Jo-1) antibody was negative.

High-Resolution CT Scan Findings

A high-resolution CT scan (HRCT) of the patient's upper lung zones depicted minimal peripheral reticular opacities. Mid-lung zones exhibited fine reticular changes at the pleural surface with minimal changes in the peripheral areas and intermittent reticular abnormalities. Lower lung zones depicted asymmetric reticular changes predominantly on the right, with some cystic changes that occurred primarily in the middle of the lung rather than on the periphery. Honeycomb changes were present but not extensive (Figs 1-3).

Pathology Findings

There was evidence of fibrosis with mild chronic inflammation adjacent to areas of fibrosis, and microscopic honeycombing was present. Temporal and spatial heterogeneity were also shown, with fibrosis at the periphery and a transition to areas of normal lung. Fibroblastic foci were present. The biopsy specimen was typical for usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) [Figs 4-7].

Clinical Course

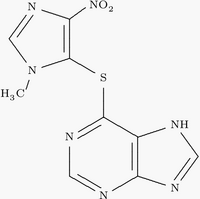

UIP was diagnosed. The patient was treated with prednisone and azathioprine for 6 months, according to the American Thoracic Society recommendations. (1) However, his lung disease continued to progress, and at 6 months his FVC was 67% predicted, TLC was 65%, and DLCO was 59%.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates the value of obtaining surgical lung biopsy specimens from more than one lobe of the lung. Since this patient had areas resembling both nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) and UIP on the biopsy specimen, NSIP may have been diagnosed if a single biopsy specimen had shown NSIP. When areas of NSIP and UIP are both present on a biopsy specimen, the clinical course appears to be more typical of UIP than NSIP. Patients with elements of both fibrotic NSIP and UIP have a worse prognosis compared to patients with fibrotic NSIP alone. (2) Furthermore, the importance of identifying areas of normal lung in the pathology of UIP is demonstrated.

The usefulness of a 6-min walk test goes beyond assessing diagnosis and requirements for supplemental oxygen with exertion. Exercise-induced hypoxia is also an index of the severity of interstitial lung disease and can define prognosis in terms of mortality. Lama and colleagues (3) followed up 83 consecutive patients with biopsy-proven UIP with a 6-min walk test and found that patients with oxygen desaturation (defined as arterial oxygen saturation of < 88%) had significantly reduced survival times when compared to those who did not experience desaturation (p = 0.0018). Patients with UIP who experienced oxygen desaturation during a 6-min walk test had 4.2 times the risk of death when compared to the UIP patients who did not experience oxygen desaturation. The relative 4-year survival rates for patients with UIP in this study were 69% for those patients who did not experience desaturation during the 6-min walk test and 35% for those patients who did. Since this patient experienced only minimal oxygen desaturation (95 to 92%) during the 6-min walk test, a better prognosis was expected.

Another aspect of the clinical evaluation in patients who are suspected of having an interstitial lung disease is serologic testing to exclude collagen vascular diseases that may mimic idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). These tests should be appropriately tailored to the clinical situation. For example, an ANA titer helps to determine whether an autoimmune disease is present. Specifically, aldolase, creatine phosphokinase, and anti-Jo-1 antibody tests assist in identifying the possibility of coexisting dermatomyositis/polymyositis; rheumatoid factor aids in the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis; SCL-70 identifies SCL; RNP is also helpful for diagnosing mixed connective tissue disease; and both SSA and SSB are utilized for diagnosing Sjogren syndrome. Patients with ILD in the setting of an autoimmune disease have an improved prognosis compared to patients with IPF/UIP. (4)

CLINICAL PEARLS

* If a surgical lung biopsy is required, biopsy specimens should be obtained from more than one lobe of the lung.

* If areas of NSIP and UIP are present on the lung biopsy specimen, then UIP determines the prognosis.

* Oxygen desaturation of < 88% on a 6-min walk test is a predictor of decreased survival in UIP patients.

* Serology is useful for excluding collagen vascular diseases that may mimic IPF and for excluding other causes of diffuse parenchymal lung disease. However, serologic tests do not confirm a diagnosis of IPF.

CASE 2: 40-YEAR-OLD MAN WITH URTICARIAL RASH AND CHEST TIGHTNESS WITH EXERTIONAL BREATHLESSNESS

A 49-year-old man developed a migratory urticarial rash 5 months prior to presentation that continued to persist. He had no history of respiratory disease, and reported chest tightness with exertional breathlessness and minimal cough. The patient had noticed hand swelling and stiffness, but denied other joint pains. He also denied fever, chills, nausea, anorexia, muscle weakness, dysphagia, and hemoptysis.

The patient is a professor of marine biology, is an expert on coral, and breeds Siamese fighting fish. He works in a musty office building with poor ventilation. He is a former smoker and was treated for Lyme disease in 1999. Upon review of systems, he denied Raynaud symptoms, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and aspiration.

Physical Examination

The patient was afebrile. A skin examination revealed an erythematous blanching rash on the back. Digital clubbing was absent. Chest auscultation revealed late inspiratory squeaks and crackles in both bases without pleural rob. Pulmonary function studies demonstrated the following: FE[V.sub.1], 2.2 L (56% predicted); FVC, 2.8 L (50% predicted); TLC, 4.6 L (57% predicted); and DLCO, 31%. During a 6-min walk test performed on a flat surface, oxygen saturation declined from 91 to 72%.

Laboratory Findings

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 45 mm/h, the test for ANAs was negative, rheumatoid factor level was normal, the test for SSA antibodies was positive, the test for SSB antibodies was negative, the tests for RNP and SCL-70 antibodies were negative, the aldolase level was normal at 5.6 U/L, and the test for the anti-Jo-1 antibody was negative.

HRCT Scan Findings

(See Figures 8-12)

Pathology Findings

Pathologist 1: The biopsy specimen showed an active fibrosing process that fit best with bronchiolitis obliterans-organizing pneumonia. It was characterized by extensive intraluminal active fibrosis involving small bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveolar spaces. Focally, eosinophils are prominent, but this is not a diffuse change and does not fit with a variant of eosinophilic pneumonia. Very little irreversible fibrosis is present, and the expectation would be that the patient would recover much of his lung function (Figs 13-19).

Pathologist 2: The biopsy specimen showed diffuse lung injury with extensive organization. Type II pneumocyte hypertrophy was diffusely present. Fibrin was identified in some alveoli, although hyaline membranes were not present. Honeycombing was seen focally. Pockets of eosinophils were apparent, both within alveoli and in the interstitium.

Pathologist 3: Organizing acute lung injury associated with extravascular tissue eosinophils was diagnosed. Focal pleuritis and pleural adhesion formation was seen. Some mucostasis was present, suggesting small airways disease.

Clinical Course

The patient began treatment with prednisone but had no clinical improvement despite 3 months of therapy with prednisone, 60 mg daily. Cyclophosphamide was added to the regimen, and after 2 months of treatment at 150 mg daily orally there was both improvement in exertional breathlessness and cough cessation. Pulmonary function improved with the following levels observed after 15 months: FVC, 4.76 L (87% predicted); TLC, 6.1 L (77% predicted); and DLCO, 17.8 L (60%). However, the patient continued experiencing oxygen desaturation with exertion.

DISCUSSION

This patient presented with the subacute onset of interstitial lung disease, with an isolated positive connective tissue disease serology, and predominantly lower lung zone infiltrates. The biopsy specimen revealed a spectrum of organizing pneumonia with interstitial pneumonitis. Although the patient experienced a clinical response to therapy with prednisone and cyclophosphamide, exertional hypoxemia persisted. The important point of this case is that despite a surgical lung biopsy specimen that revealed organizing pneumonia and eosinophilic infiltrates there was no clinical improvement with corticosteroid treatment alone. Most patients with a diagnosis of organizing pneumonia confirmed by a surgical lung biopsy specimen will improve with corticosteroid therapy. (5,6) The term bronchiolitis obliteransorganizing pneumonia has been replaced with cryptogenic organizing pneumonia in a more recent classification system. (6) Although most patients with organizing pneumonia respond to immunosuppressive treatment, a subset of patients can be refractory to treatment. (7)

The discrepancies in the pathologist evaluation demonstrate interobserver variability. Nicholson and colleagues (8) evaluated the interobserver variability among 10 pathologists from the UK Interstitial Lung Disease panel. Investigators found only fair agreement among pathologists in their first choice of diagnosis (K = 0.38), but agreement among pathologists regarding diagnosis increased when multiple biopsy specimens were obtained (K = 0.43). As in this case, these findings show that even pathologists who routinely evaluate ILDs often disagree about the histologic diagnosis, even when the diagnosis is based on multiple biopsy specimens. However, the important point was that none of the pathologists thought the diagnosis was UIP. The interobserver variability is better when comparing UIP with non-UIP. This is important because patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias other than UIP often respond better to immunosuppressive therapy, as evidenced in this case.

As was done with this patient, the discussion of lung transplant should take place early in the disease process. Patients should consider registering on the transplant list early, as the waiting time for an organ may exceed 2 years, and, unfortunately, many patients with rapidly progressing disease may die while awaiting transplantation. (9)

Patients with ILD and an autoimmune disease may have the lung disease precede other manifestations of a connective tissue disease process. Evaluating patients over time, particularly when the immunosuppression therapy is reduced, may uncover the activation of a latent autoimmune disease. (10)

CLINICAL PEARLS

* Desaturation to < 88% on a 6-minute walk test is a predictor of decreased survival in patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias.

* Recent data demonstrate that pathologists who routinely evaluate interstitial lung diseases often disagree about the histologic diagnosis, even when the diagnosis is based on multiple biopsy specimens,

* Patients should consider registering on the transplant list early, even before a significant decline in lung function is experienced.

* The lung may be precede joint involvement in patients with autoimmune diseases.

REFERENCES

(1) American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment; international consensus statement--American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161:646-664

(2) Flaherty KR, Thwaite EL, Kazerooni EA, et al. Radiological versus histological diagnosis in UIP and NSIP: survival implications. Thorax 2003; 58:143-148

(3) Lama VN, Flaherty KR, Toews GB, et al. Prognostic value of desaturation during a 6-minute walk test in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 168:1084-1090

(4) Bouros D, Wells AV, Nicholson AG, et al. Histopathologic subsets of fibrosing alveolitis in patients with systemic sclerosis and their relationship to outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 165:1581-1586

(5) Epler GR. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161:158-164

(6) Cordier JF. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Clin Chest Med 2004; 25:727-738, vi-vii

(7) Cohen AJ, King TE, Downey GP. Rapidly progressive bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994; 149:1670-1675

(8) Nicholson AG, Addis BJ, Bharucha H, et al. Inter-observer variation between pathologists in diffuse parenchymal lung disease. Thorax 2994; 59:500-505

(9) American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; diagnosis and treatment--international consensus statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161:646-664

(10) Tansey D, Wells AV, Colby TV, et al. Variations in histological patterns of interstitial pneumonia between connective tissue disorders and their relations to prognosis. Histopathology 2004; 44:585-596

* From the Pulmonary and Critical Care Section (Drs. Noble and Tanoue), Department of Pathology (Dr. Homer), Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT.

Dr. Noble has received speaking honoraria from InterMune Pharmaceuticals, Genzyme, and Millennium.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestjournal. org/misc/reprints.shtml).

Correspondence to: Paul W. Noble, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care Section, Yale University School of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, 333 Cedar St, PO Box 2080.57, New Haven, CT 06520-8057; e-mail: Paul.noble@yale.edu

COPYRIGHT 2005 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group