Abstract

Methotrexate-related hematologic toxicity may include leakopenia, thrombocytopenia, megaloblastic anemia, and pancytopenia. We report a woman with hypertensive renal disease who was receiving hemodialysis and developed pancytopenia following a single intradermal infiltration of 25 mg of methotrexate. Caution should be exercised when considering the use of either systemic or intralesional methotrexate therapy in patients with risk factors that have been implicated in the development of adverse hematologic side effects: renal dysfunction, possible drug interactions, and advanced age.

Introduction

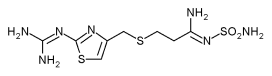

Methotrexate is a folic acid antagonist that acts by inhibiting dihydrofolate reductase. (1,2) Intralesional administration of methotrexate has been successfully utilized to treat keratoacanthoma. (3,4) We report a woman who developed pancytopenia after a single postoperative intradermal injection of methotrexate into the skin adjacent to the surgical site following the partial closure of the wound.

Case Report

A 39-year-old Caucasian woman developed a new lesion on her left arm. Her past medical history was significant for numerous cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas, hypertension, and renal disease requiring hemodialysis 3 times weekly on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday; she had previously rejected 2 kidneys that had been transplanted 19 and 9 years earlier. Her current medications included amlodipine besylate, atorvastatin calcium, calcium carbonate, clonidine, conjugated estrogens, doxazosin, epoetin alfa (3 times each week), famotidine, ferric sulfate, fish oil, folic acid (2 mg each day), furosemide, gemfibrozil, labetalol hydrochloride, multivitamins, prednisone (5 mg each day), sirolimus, and sodium bicarbonate.

Examination of her left distal extensor arm showed a 2.5 X 4.0 cm ulcerated red plaque; there was no palpable lymphadenopathy. A lesional skin biopsy revealed a squamous cell carcinoma and Mohs micrographic surgery was used to excise the cancer. Prophylactic antibiotics (cephalexin 250 mg, 4 times each day, beginning 1 day prior to surgery and treating for a total of 7 days) were used. The tumor was clear after the second stage of Mohs surgery and the defect was repaired using a complex closure; a small portion of the central defect was allowed to heal by granulation. Based on the successful management of keratoacanthomas with intralesional methotrexate, 25 mg of methotrexate (2 ml of 12.5 mg/ml), which had been diluted in bacteriostatic saline, was injected intradermally into the area which had surrounded the tumor.

The patient missed her regularly scheduled Friday dialysis (which was the day following surgery). Her next dialysis was Monday (which was 4 days after the removal of her cancer and treatment of the tumor site with intralesional methotrexate). Her surgical site was healing well when she returned for a postoperative visit after 1 week; however, in addition to tenderness and erythema of her posterior pharynx, she had painful hemorrhagic erosions on the vestibule of her lower lip and her buccal mucosa bilaterally. The initial differential diagnosis included erosive candidiasis, herpes simplex virus infection, and erythema multiforme. She was treated with fluconazole (100 mg after each dialysis X 4 doses), valacyclovir (500 mg after each dialysis X 4 doses), and salt water mouth rinses.

She returned 3 days later. Although her mucositis had improved, she had intermittent epistaxis for the previous 2 days and had developed new petechiae on both of her arms. The possibility of methotrexate toxicity was considered and laboratory studies were performed (Table 1). Although her serum methotrexate level was undetectable, she was pancytopenic.

Precautions to prevent infection were discussed. Levaquin 500 mg every 48 hours X 5 doses was empirically started because of her severe neutropenia. Her complete blood counts were determined 3 times weekly at each of her dialysis treatments. Within the next few weeks, her complete blood cell counts returned to normal, the oral ulcerations healed completely, the episodes of epistaxis ceased, and the petechiae resolved without recurrence.

Discussion

Methotrexate toxicity is usually associated with the systemic administration of the drug--either orally, intramuscularly, or intravenously. Minor toxic effects may include alopecia, diarrhea, dizziness, fatigue, fever, headaches, malaise, mood alteration, myalgias, nausea, polyarthralgia, and increased size of rheumatoid nodules. (1,5) These effects may be associated with depletion of folate. Therefore, for all patients being treated with methotrexate, supplementation with either 1 mg daily or 7 mg once weekly of folate should be considered. (1)

Major toxic effects occur less frequently than minor adverse side effects, may be life threatening, and can involve the bone marrow, kidney, liver, and lungs. (1,6,7) Hematologic toxicity includes leukopenia, megaloblastic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and pancytopenia. In patients with rheumatoid arthritis who are treated with methotrexate, the estimated prevalence of drug-associated hematologic toxicity is 3% and the incidence of pancytopenia in these individuals is approximately 1.4%. (6,7) The pancytopenia, which can be fatal, has been reported to have occurred at a minimum cumulative methotrexate dose of 10 mg. (7)

The most important determinant of significant methotrexate toxicity--including hematologic effects--is the presence of renal impairment. Other risk factors may also contribute to the frequency and severity of bone marrow toxicity. These include advanced age, increased alcohol ingestion, diabetes, folic acid deficiency, hypoalbuminemia, infections, and obesity. In addition, the concomitant use of drugs that decrease the renal excretion of methotrexate, such as probenecid or antibiotics (penicillin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole), increases the risk of hematologic toxicity. (6,7)

The use of intralesional methotrexate is usually not associated with the occurrence of drug-associated side effects. (3) However, in addition to our patient, a 69-year-old man with a keratoacanthoma on the nose developed pancytopenia after a treatment with a single lesional methotrexate infiltration of 12.5 mg (Table 1). (8) This individual, similar to our patient, had a history of chronic renal failure requiring hemodialysis. (8)

Conclusion

Methotrexate-related pancytopenia can result not only after the systemic administration of methotrexate, but also following an intralesional cutaneous infiltration of the drug. Also, similar to pancytopenia following systemically-received methotrexate, intralesional methotrexate-associated pancytopenia can occur after a low cumulative dose of therapy. This toxicity can even result after just the initial treatment. Therefore, it is important to exercise increased caution when considering the use of intralesional methotrexate therapy in patients who have risk factors--such as renal dysfunction, possible drug interactions, and advanced age--that have been directly implicated in the development of pancytopenia.

References

1. Jones KW, Patel SR. A family physician's guide to monitoring methotrexate. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:1607-1612, 1614.

2. Olsen EA. The pharmacology of methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:306-318.

3. Melton JL, Nelson BR, Stough DB, Brown MD, Swanson NA, Johnson TM. Treatment of keratoacanthomas with intralesional methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1017-1023.

4. Cohen PR, Schulze KE, Teller CF, Nelson BR. Intralesional methotrexate as effective treatment for keratoacanthoma of the nose. SkinMED: Dermatology for the Clinician. In press.

5. Williams FM, Cohen PR, Arnett FC. Accelerated cutaneous nodulosis during methotrexate therapy in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:359-362.

6. Weinblatt ME. Toxicity of low dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1985;12(suppl 12):35-39.

7. Gutierrez-Urena S, Molina JF, Garcia CO, Cuellar ML, Espinoza LB. Pancytopenia secondary to methotrexate therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:272-276.

8. Goebeler M, Lurz C, Kolve-Goebeler M-E, Brocker E-B. Pancytopenia after treatment of keratoacanthoma by single lesional methotrexate infiltration. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1104-1105.

Address for Correspondence

Bruce R. Nelson MD

Dermatologic Surgery Center of Houston

6655 Travis, Suite 840

Houston, TX 77030-1342

e-mail: bnelson@dermsurgeryhouston.com

Philip R. Cohen MD, (a,b) Keith E. Schulze MD, (a) Bruce R. Nelson MD (a)

a. Dermatologic Surgery Center of Houston, PA, Houston, TX

b. Department of Dermatology, University of Texas-Houston Medical School, Houston, TX

COPYRIGHT 2005 Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group