This was a prospective study performed in a Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center. The aim of this study was to use endoscopic and histological examinations to determine the potential diagnostic origins of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms among patients who were part of the deployment of troops to the Persian Gulf after August 1990. Twenty-four (8%) male patients (mean age, 42 years) of 308 patients in the Persian Gulf War Registry agreed to undergo endoscopic examination of chronic symptoms, including heartburn (29%), dyspepsia (33%), dysphagia (8%), diarrhea (63%), Hemoccultpositive stool (21%), and rectal bleeding (17%). There were 17 upper endoscopies, 18 colonoscopies, and 4 flexible sigmoidoscopies performed, all with biopsies. Five (33%) of 15 patients had positive serological findings for Helicobacter pylori. With upper endoscopy, major findings included esophagitis (12%), Schatzki's ring (12%), hiatal hernia (47%), antral erythema (59%), and duodenal erythema (29%). With lower endoscopy, major findings included ileitis (5%), lymphoid hyperplasia (9%), polyps (27%), diverticulosis (23%), and hemorrhoids (23%). Major histopathological findings included microscopic esophagitis (24%), gastritis with H. pylori (35%), gastritis without H. pylori (18%), Crohn's disease (5%), tubular adenoma (5%), hyperplastic polyps (18%), and melanosis coli (5%). Most patients with chronic heartburn or dyspepsia have evidence of esophagitis or H. pylori. Individuals with these chronic symptoms should undergo evaluation.

Introduction

In August 1990, the United States began deployment of 697,000 troops to the Persian Gulf region.1 Of these troops, 77,000 individuals were being compensated by the U.S. government for chronic symptoms and another 23,000 individuals were awaiting a decision on compensation for their chronic symptoms in 1998.2

Prevalence data for chronic symptoms obtained from registries developed after the Persian Gulf War have yielded variable results. In the original registry developed by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), 48,251 individuals were included and diarrhea was reported by 5% of these individuals.1 In a more recent registry developed by the Department of VA, 9,002 individuals were included and diarrhea was reported by 14% of these individuals.1 The Department of Defense has had a separate evaluation program; of 27,747 individuals registered in this program, diarrhea was reported by 27%.1

Epidemiological studies of troops from the United States have also been performed. In surveys of National Guard units from Pennsylvania and another state, the prevalence of chronic symptoms in four units deployed to the Persian Gulf was examined and compared with that in four units that were not deployed to the Persian Gulf War.3 The size of the units deployed to the Persian Gulf War ranged from 119 to 470 individuals. The prevalence of diarrhea among these individuals ranged from 10 to 27%, and the prevalence of gastrointestinal gas and pain ranged from 18 to 38%. By comparison, the size of the units not deployed to the Persian Gulf ranged from 364 to 1,397 individuals. The prevalence of diarrhea among nondeployed troops ranged from 2 to 3%, and the prevalence of gastrointestinal gas and pain ranged from 10 to 14%.

An epidemiological study of a single National Guard unit has also been reported from Boston, Massachusetts.4 This study included 57 individuals who had served in the Persian Gulf War and 44 individuals who had not been deployed. The current presence of abdominal pain was reported by 70% of the deployed troops compared with 9% of the control group. The current presence of loose bowel movements was reported by 74% of deployed individuals compared with 18% of control subjects. The current presence of excessive gas was reported by 74% of deployed individuals compared with 23% of control subjects. Current nausea or emesis was reported by 23% of deployed individuals compared with 2% of control subjects. Current heartburn was reported by 33% of deployed individuals compared with 7% of control subjects.

Chronic gastrointestinal symptoms have also been reported by other Persian Gulf War coalition troops. There was deployment of 53,462 British troops. In a medical assessment program, 1,000 patients were initially examined, of whom 21.8% received a diagnosis of vomiting, diarrhea, or stomach problems.5 In a postal survey, flatulence or burping was reported by 34.1% of individuals deployed to the Persian Gulf region, whereas these symptoms were reported by 16.4% of individuals who had been deployed in Bosnia.6,7 Among Danish Persian Gulf War veterans, the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms was 9.1% compared with 1.7% among age-, gender-, and professionmatched control subjects.8 Questionnaire data8 suggested that patients with chronic symptoms might have suffered an environmental exposure (burning of waste or manure, contact with insecticide, or tooth brushing with, bathing in, or drinking of contaminated water).

Despite multiple epidemiological studies documenting the presence of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms, there is a dearth of information concerning the reasons why patients present with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. The aim of this study was to use endoscopic and histological examinations to determine the potential diagnostic origins of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms among patients who were part of the deployment to the Persian Gulf. This prospective study included evaluation of laboratory results, endoscopic findings, and histopathological examination of biopsies obtained from veterans who were referred to the gastroenterology clinic because of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms that developed during and after service in the Persian Gulf War.

Methods

Permission for human studies was granted by the Human Studies Subcommittee at the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center in Clarksburg, West Virginia, on September 25, 1997. At the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center, there is a formal Persian Gulf War Registry that includes 308 patients and is made up of individuals who have been seen for evaluation of chronic symptoms for potential compensation by the U.S. government. This was a prospective study performed in a Department of VA Medical Center with patients who were included in the Persian Gulf War Registry and who were referred to the gastroenterology clinic for further evaluation of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms that developed during or after the Persian Gulf War.

In this study, dyspepsia was defined as episodic upper abdominal pain or discomfort.9 Heartburn was defined as pyrosis or regurgitation into the chest, or both.10 Chronic diarrhea was defined as a >3-week difficulty with an increase in the patient's stool frequency or a change in fluid consistency.11

Twenty-four male patients (8%) agreed to undergo endoscopic examination for further evaluation of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms (Table I). Their age range was 26 to 62 years, with a mean of 42 years. The upper intestinal symptoms for which patients were referred to the gastroenterology clinic included chronic heartburn (29%), chronic dyspepsia (33%), chronic nausea (4%), hematemesis (4%), and dysphagia (8%). The lower intestinal symptoms for which patients were referred to the gastroenterology clinic included chronic diarrhea (63%), rectal bleeding (17%), Hemoccult-positive stool (21%), and fecal incontinence (4%).

Laboratory testing was offered to all patients to examine infectious or endocrine origins for chronic diarrhea or dyspepsia. All patient histories, physical examinations, and endoscopic procedures were performed by one of us (T.R.K.). Endoscopy was then performed with a video-endoscopy system. Seventeen patients underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy, with three or four routine biopsies being obtained from the distal duodenum, the gastric antrum and body, and the distal esophagus. Eighteen patients underwent colonoscopy, with three or four routine biopsies being obtained from the ileum, ascending colon, descending colon, and rectum. Four patients underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy, with three or four routine biopsies being obtained from the sigmoid colon and rectum. These biopsies were incubated overnight in Formalin, embedded, sectioned, and stained with the hematoxylin and eosin method. All biopsies were then sent to the Armed Forced Institute of Pathology in Washington, DC, and reviewed by one of us (T.S.E.).

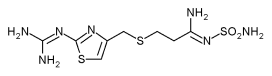

At the time of evaluation and at the time of endoscopy, no patient was being treated with a hydrogen/potassium-ATPase inhibitor. Of these 24 patients, 9 patients were being treated with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (ibuprofen, 7; indomethacin, 1; aspirin, 1). Of the 24 patients, 8 patients were being treated with a histamine-2 receptor antagonist (ranitidine, 3; cimetidine, 4; famotidine, 1). Four patients were simultaneously receiving a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug and a histamine-2 receptor antagonist.

Results

Laboratory Evaluations

The majority of the patients in this study completed laboratory evaluations to examine potential endocrine and infectious causes of diarrhea and dyspepsia (Table II). These studies included normal serum creatinine, glucose, and potassium levels for all patients. Thyroid-stimulating hormone and serum albumin levels were normal for all 23 patients examined, and serum calcium levels were normal for all 19 patients examined. Erythrocyte sedimentation rates were normal for all 17 patients tested. Fifteen patients underwent Helicobacter pylon serological testing and five (33%) had significant elevations of their antibody titers. All patients had normal white blood cell counts, hemoglobin levels, platelet counts, and mean corpuscular volumes, and there was no evidence of eosinophilia. Leishmaniasis serology was obtained for 16 patients, and all tests were negative. Lactose tolerance tests were performed for 12 patients, and 1 patient had evidence of lactose intolerance. A normal lactose tolerance test was defined by a peak glucose level that was >30 mg/dL over baseline, 20 minutes after a 50-g oral dose of lactose. Stool ova and parasite examinations were negative for eight patients. Stool cultures yielded only normal fecal flora for six patients and, in eight stool examinations for fecal leukocytes, only one patient had a few neutrophils identified.

Upper Endoscopic Findings

Seventeen patients underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (Table III). Among these patients, two patients had evidence of esophagitis (12%) and two patients had a Schatzki's ring (12%). Eight patients had a hiatal hernia (47%) and one patient had a gastric polyp (6%). Ten patients were noted to have antral erythema (59%) and one patient had a gastric ulcer (6%). Five patients had duodenal erythema (29%) and one patient had a duodenal ulcer (6%).

Lower Endoscopic Findings

Eighteen patients underwent colonoscopy with routine intubation of the terminal ileum and four patients underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy (Table III). Ileltis consistent with Crohn's disease of the terminal ileum was identified in one patient (5%). Two patients had lymphoid hyperplasia (9%). Six patients had colonic polyps (27%), five patients had diverticulosis (23%), and five patients had hemorrhoids (23%).

Histological Findings

Among the histological findings (Table IV) from examination of biopsies obtained at upper endoscopy, four patients had microscopic esophagitis (24%) and six patients had gastritis associated with H. pylon (35%). Three patients had gastritis without evidence of H. pylori (18%).

During examination of biopsies obtained at lower endoscopy (Table IV), one patient had evidence of Crohn's disease of the ileum (5%). One patient had a tubular adenoma (5%) and four patients had hyperplastic polyps (18%). Melanosis coli was identified in one patient (5%).

Among the nine patients receiving a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, seven patients underwent upper endoscopy and six patients underwent lower endoscopy. Among the seven patients who underwent upper endoscopy, gastric biopsies were normal for four individuals, with one case interpreted as gastritis with H. pylori and two cases interpreted as gastritis without H. pylori Among the six patients who underwent lower endoscopy, colon and rectal biopsies were normal for four individuals, with one patient with hyperplastic polyps and one patient with melanosis coli.

Discussion

We are unaware of any complete reports describing medical diagnoses among patients with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms after Persian Gulf War exposure. The U.S. Senate Committee on Veteran's Affairs, in their summary report stated that these veterans are suffering from unexplained illnesses.1 The concern that initiated the present study was that such a position suggests that Persian Gulf War veterans do not have identifiable gastrointestinal disorders and evaluation of patient symptoms would therefore be unrewarding.

The patients in the present study did not fulfill the diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome, as defined by either the Rome I criteria12 or the Manning criteria, requiring ≥3 symptoms. 13 We propose that the results of the present study support the evaluation of patients with symptoms after Persian Gulf War exposure. Evaluation of patients with upper intestinal symptoms would more likely be diagnostically useful, compared with evaluation of patients with chronic diarrhea alone. Because of the size of the present study, it would be difficult to extrapolate its results to all individuals with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms who served in the Persian Gulf War region. In addition, the patients in the present study live in a rural environment and might be exposed to other environmental agents.

Among patients with upper intestinal symptoms, the majority of patients were found to have evidence either of gastroesophageal reflux disease (as manifested by endoscopic esophagitis, Schatzki's ring, or microscopic esophagitis) or of antral gastritis, related either to H. pylori infection or to the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in two patients. In addition, two patients had gastroduodenal ulcer disease. Our finding of gastroesophageal reflux disease would be consistent with a previous study that reported pulmonary and laryngeal complications among Persian Gulf War veterans.14 Because the patients in the present study had not received treatment with proton pump inhibitors, the potential benefit of treatment with high-dose therapy for ≥3 months is presently unknown.

The presence of antral gastritis was likely related to H. pylori infection for six patients and to the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs for two patients. Presently, it is unclear but possible that eradication of H. pylon infection among patients with nonulcer dyspepsia may lead to long-term symptomatic relief.1516 It is unclear but possible that discontinuation of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or conversion to cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory agents for patients with nonulcer dyspepsia may lead to long-term symptomatic relief. Because this prospective study was not designed as a treatment trial, there were no results obtained to examine these possible therapeutic alternatives.

The origin and mechanisms for the development of chronic diarrhea among these patients remain major questions. This study examined the mucosal responses of patients after Persian Gulf War exposure with endoscopic and histopathological examinations. We are unaware of complete colonic motility studies or colonie perfusion studies of patients with chronic diarrhea after Persian Gulf War exposure.

The identification of chronic symptoms among individuals after their presence at a common location suggests exposure to a yet unidentified environmental agent. There has been an extensive focus on the possibility that chronic symptoms among these patients might have resulted from exposures suffered by these individuals during their service in the Persian Gulf.17 Self-reported exposures included antidote given for potential exposure to chemical warfare agents (pyridostigmine), solvents or petrochemicals, smoke or combustion products, infectious diseases (including leishmaniasis), psychological stress, lead from fuels, pesticides, radiation (spent uranium used in shells), physical trauma, and possible chemical warfare agents.17

Of these potential exposures, there has been extensive evaluation of the potential for exposure to contamination during and after the demolition of a chemical depot in Khamisiyah, Iraq, on March 10, 1991.18 This chemical depot contained sarin and cyclosarin. Based on a meteorological model, it was predicted that a plume or cloud created by demolition could have led to the exposure of 98,910 troops. Among the problems with this model, troop locations during the Persian Gulf War remain uncertain. Among the patients in the present study, few were certain of their locations during the time period of interest. Of interest, individuals who did know their locations during the conflict often came to their gastroenterology clinic visits carrying still photographs of the purported explosion and in one instance carrying a videotape of the purported demolition. Because other sites were destroyed during the Persian Gulf War, it is possible that the development of chronic symptoms among 100,000 U.S. troops could be related to an additional but as yet unidentified exposure.

In toxicology studies, exposure to individual agents does not seem sufficient to explain the symptoms described by Persian Gulf War veterans. There have been preliminary data from an animal model that show that individual exposures are minimally toxic.19 However, with administration of two agents in combinations that included pyridostigmine bromide, permethrin, and JV.lV-diethyl-m-toluamide (insect repellent), there was enhanced neurotoxicity.19

We suggest that additional work should be encouraged to develop potential markers that could be used to screen patients with Persian Gulf War exposure and chronic diarrhea. These potential markers could include mediators of immunity or cytokines, tissue antioxidants, neurotransmitters and their receptors, or products of apoptosis. Without the availability of a marker, it will remain difficult for physicians to screen and evaluate patients with chronic diarrhea.

Acknowledgments

Published Persian Gulf War documents were obtained from the offices of the United States Senate. We thank Colonel John Graham. British Liaison Officer (Gulf Health), for his helpful discussions in the preparation of this work.

References

1. Committee on Veterans' Affairs, United States Senate: Report of the Special Investigation Unit on Gulf War Illnesses. S. PRT 105-39, Part I. Washington, DC, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1998.

2. Committee on Veterans' Affairs, United States Senate: Report of the Special Investigation Unit on Gulf War Illnesses. S. PRT 105-39, Part II. Washington. DC, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1998.

3. Kizer KW, Joseph S, Moll M, et al: Unexplained illness among Persian Gulf War veterans in an Air National Guard unit: preliminary report: August 1990-March 1995. MMWR 1995; 44: 443-7.

4. Sostek MB, Jackson S, Linevsky JK, et al: High prevalence of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms in a National Guard Unit of Persian Gulf veterans. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91: 2494-7.

5. Coker WJ, Bhatt BM, Blatchley NF, et al: Clinical findings for the first 1000 Gulf War veterans in the Ministry of Defence's medical assessment programme. Br Med J 1999:318:290-4.

6. Unwin C, Blatchley N, Coker W, et al: Health of UK servicemen who served in Persian Gulf War. Lancet 1999; 353: 169-78.

7. Coker WJ: A review of Gulf War illness. J R Navy Med Serv 1996; 82: 141-6.

8. Ishoy T, Suadicani P, Guldager B, et al: Risk factors for gastrointestinal symptoms. Dan Med Bull 1999; 46: 420-3.

9. Fisher RS. Parkman HP: Management of nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 1376-81.

10. DeVault KR, Castell DO: Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94: 1434-42.

11. Ammon HV, Koch TR: Diarrhea and constipation. In: Bockus Gastroenterology, Ed 5, pp 87-112. Edited by Haubrich WS, Schaffner F, Berk JE. Philadelphia. PA, WB Saunders, 1995.

12. American Gastroenterological Association: American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1997; 112:2118-9.

13. Camilleri M, Prather CM: The irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and a practical approach to management. Ann Intern Med 1992; 116: 1001-8.

14. Das AK, Davanzo LD. Poiani GJ, et al: Variable extrathoracic airflow obstruction and chronic laryngotracheitis in Gulf War veterans. Chest 1999; 115: 97-101.

15. Slum AL, Talley NJ, O'Morain C, et al: Lack of effect of treating Helicobacter pylori infection inpatients with nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 1875-81.

16. McColl K, Murray L, El-Omar E, et al: Symptomatic benefit from eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 1869-74.

17. Iowa Persian Gulf Study Group: Self-reported illness and health status among Gulf War veterans: a population-based study. JAMA 1997; 277: 238-45.

18. Gray GC. Smith TC, Knoke JD, et al: The postwar hospitalization experience of Gulf War veterans possibly exposed to chemical munitions destruction at Khamishiyah, Iraq. Am J Epidemiol 1999; 150: 532-40.

19. Abou-Donia MB, Wilmarth KR, Jensen KF, et al: Neurotoxicity resulting from coexposure to pyridostigmine bromide, DEET, and permethrin: implications of Gulf War chemical exposures. J Toxicol Environ Health 1996; 48: 35-56.

Guarantor: Timothy R. Koch, MD

Contributors: Timothy R. Koch, MD*[dagger]; Theresa S. Emory, MD[double dagger]

* Lewis A. Johnson Veterans Affairs Medical Center, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV.

[dagger] Current address: Section of Gastroenterology, Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC 20010.

[double dagger] Division of Gastrointestinal Pathology, Department of Hepatic and Gastrointestinal Pathology, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC 20306-6000.

This manuscript was received for review in January 2003 and was accepted for publication in March 2003,

Reprint & Copyright @ by Association of Military Surgeons of U.S., 2005.

Copyright Association of Military Surgeons of the United States Aug 2005

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved