George Thomas was 21 years old when his life changed: As he stood in his girlfriend's yard, he was hit by a car. After spending a week in the hospital, he was released. But over the next five years, the athletic Thomas began experiencing dizzy spells. At first he shrugged them off as a result of over-exercise or bad diet.

"Then one day I crashed right out of the shower," Thomas recalls. "After that I had frequent grand mal seizures."

The diagnosis was epilepsy, a disease with myriad causes, one of which is the kind of head injury Thomas experienced. The seizures totally changed his active, athletic lifestyle.

"I couldn't ride my bike, I was too dizzy," says Thomas, a cross-country cyclist. "My vision stunk. I had my driver's license taken away; when I had to write a check, people would ask why a guy in his mid-20s didn't have a license. The word epilepsy was a stigma."

Thomas tried a variety of anticonvulsant medications, taking up to 16 pills a day at one point. One day, as his wife drove the newly married Thomas to a doctor's appointment, he had a terrible seizure. He couldn't move, and he threw up all over himself.

"My doctor said we'd try to look at something else," he says.

"Something else" was Thomas' decision to become part of clinical trials for a new drug called Lamictal (lamotrigine) in 1989, which was subsequently approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1994. He has not had a seizure since. Today the 35-year-old Thomas is the father of a 7-year-old daughter, a professional speaker, and an "ultra distance" bicycle racing champion who races bikes cross country.

Thomas has plenty of company when it comes to battling epilepsy. Over 2 million people in America have the disorder, and the worldwide numbers--50 million estimated cases--are even more staggering. On a global basis, nearly three-quarters of those with epilepsy receive no treatment for their seizures. Shrouded in mystery since ancient times, epilepsy remains a complex and challenging condition that continues to baffle both doctors and researchers.

Although special diets and even surgery are used to prevent seizures, the most common treatment for epilepsy is daily use of anticonvulsant drugs. People with epilepsy may take medicine up to four times a day to prevent seizures; response to the various medicines depends on the individual and the type of seizures being treated.

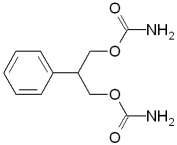

The oldest drugs used in epilepsy treatment include phenobarbital, introduced in 1912, and Dilantin (phenytoin), in use since 1938. Altogether there are nearly two dozen different drugs approved for epilepsy treatment. The most recent drugs FDA has approved include Felbatol (felbamate) and Neurontin (gabapentin), approved in 1993; Lamictal (lamotrigine), approved in 1994; Topamax (topiramate), approved in 1996; and Gabitril (tiagabine), approved in 1997.

In 1997, FDA also approved Diastat, the first at-home alternative for the intravenous form of the drug diazepam, already used by emergency rooms to break a chain of seizures. Diastat is a gel form that can be administered rectally. Designed specifically for patients affected by multiple, frequent seizures, Diastat reaches the bloodstream in about two minutes. If not halted, such seizures can be fatal.

Diastat gel has helped Eric Warner, 13, of Forest Lake, Minn., tremendously, says his mother Linda.

Following a brain infection when he was 2 months old, Eric suffered with repeated episodes of long-lasting seizures. "[Eric] started using Diastat in October 1997," Warner says. "With Diastat, you wait three minutes into the seizure, and if [it continues], you give it to him and it only takes a few minutes to work."

Warner says Diastat has cut down on trips to the emergency room with Eric. He also takes Vigabatrin, still under investigational study here, that is imported from Europe (with FDA approval, she notes) as well as Tegretol (carbamazepine).

With the help of these drugs, Warner is convinced Eric will be a writer someday.

"His strength is writing," she explains. "I look at what treatment is like now since he was first diagnosed ... there is so much research going on that I am very encouraged."

"There had not been a new chemical entity approved for epilepsy since 1978 ... the early 1990s began a new era in anticonvulsant drug approvals," says Russell Katz, M.D., deputy director of FDA's division of neuropharmacological drug products. "The research, of course, started years before that. Part of [FDA's approval of these drugs] has to do with the progress of understanding and evaluating clinical trials to evaluate these drugs. FDA has been actively working with [drug] companies to improve the science of evaluating anticonvulsant drugs." Katz adds that the National Institutes of Health also have been active in this pursuit as well.

Causes and Diagnosis

"There are at least 150 underlying causes of epilepsy," says Peter Van Hazerbeke, public relations director for The Epilepsy Foundation. In 70 percent of cases, however, no known cause of epilepsy is ever found. Some of the known causes include brain injuries, infections that damage the brain, tumors, disturbances in blood circulation to the brain (such as stroke), high fevers, lead or other poisoning, and maternal injury.

Seizures and epilepsy are not the same: Seizures are a symptom of epilepsy. Epilepsy is a neurological condition that can produce brief disturbances in the brain's electrical functions. Normally, brain cells communicate with each other via electrical impulses working together to control body movements and keep organs functioning properly. When someone has epilepsy, this normal pattern may be interrupted by thousands to millions of electrical impulses that occur at the same time and are more intense than usual, producing abnormal brain electrical activity and resulting in a seizure. These bursts of electrical impulses can affect body movements, sensations or consciousness.

Epilepsy is diagnosed mainly via interpretation of a patient's medical history; the patient describes what the seizures were like and, when a patient can't recall the seizures, witnesses also may be asked to describe what they saw.

Tests may be done to rule out short-term causes of seizures, such as uncontrolled diabetes or infections. A complete neurological exam is done, including an EEG (electroencephalogram, a machine that records brain waves picked up by wires taped to the head). Other tests may include CT (computerized tomography) scanning of the brain, MRIs (magnetic resonance imaging) to check for any growths, scars, or other brain conditions that may be causing seizures, blood tests, and even tests to check heart function. If there is any family history of epilepsy, that is also considered. (For more information about medical imaging technologies, see "The Picture of Health" in this issue of FDA Consumer.)

Although there are over 30 different types of epilepsy-related seizures, there are two broad groups--generalized or partial--depending on the part of the brain affected. Generalized seizures cause loss or alteration of consciousness, involve the entire brain, and affect the whole body. Generalized seizures include grand mal seizures, where the person falls down unconscious as the body stiffens or jerks, and petit mal or absence seizures, where there is momentary alteration of consciousness without abnormal movements. Partial seizures occur when abnormal electrical activity only involves one area of the brain. There are also two kinds of partial seizures: simple seizures, where the person remains conscious, and complex seizures, in which consciousness is lost or altered.

Most epileptic seizures last only a minute or two and are not life-threatening. However, the person who experiences repeated seizures (status epilepticus) and does not regain consciousness between attacks needs immediate attention, as does anyone with prolonged (30 minutes) seizures.

One Drug Does Not Fit All

"For someone newly diagnosed with epilepsy, they need to understand there are many different forms of epilepsy and certain types of medications seem to work best for different types of epilepsy," says Van Hazerbeke.

The need to try different medications in order to find the best combination to prevent seizures--with the fewest possible side effects--sometimes gives families the impression doctors are "experimenting" with their loved one's care, he notes.

"But this is the normal procedure for new patients until their seizures are stabilized," Van Hazerbeke says.

"Many times the side effects determine the drugs. Some drugs can make you gain weight, others have other side effects," says Robert J. DeLorenzo, M.D., a member of the Medical College of Virginia Hospitals/Virginia Commonwealth University's Epilepsy Institute and chairman of the neurology department and neurologist-in-chief at MCV Hospitals. "Taking care of epilepsy patients is an art, not just a science; you need to pick a medication that is clinically a good choice, with the least side effects for the patient. The new drugs are primarily add-on drugs for adding on [to current medications] to difficult cases."

Other Options for Bringing Seizures Under Control

In July 1997 FDA approved the first medical device for hard-to-control partial seizures. Cyberonics' NeuroCybernetic Prosthesis (NCP) system or vagus nerve stimulator, approved for adult and adolescent patients, is surgically implanted on the left side of the chest with a lead ruing under the skin to the vagus nerve an the side of the neck.

The flat, round, thin device, which includes a battery pack and computer chip, is set by a neurologist to discharge in bursts of about 30 seconds each, every five minutes a day, 24 hours a day. The stimulation has the effect of preventing seizures in some people. People generally must continue to take medications as well.

Surgery as an option for treating epilepsy is used only in rare instances.

"Anyone that has intractable epilepsy, with seizures occurring in spite of good medications, should be evaluated," DeLorenzo says. "If they have a focal area [of the brain] that can be operated on, you can either cure the seizures or make them treatable."

Forty-one-year-old Martha Curtis is one epilepsy sufferer for whom surgery worked. Diagnosed with epilepsy at age 3, her life was a haze of multiple drugs and seizures before she decided to opt for surgery.

A professional concert violinist, Curtis recalls that she would have seizures periodically on stage: "I knew what was happening and it was horrifying. The actual difficult part was I perceived I was going to be killed [by the seizure], which was much scarier than `oh no, I'm going to be embarrassed.'"

After experiencing four grand mal seizures in one month in 1990, Curtis decided to check out surgery as an option. She wound up having three operations.

"After the third surgery, I did real well ... the terror was cut off. This is magic ... I have fallen in love with uninterrupted consciousness!" she says with a laugh.

Curtis still takes two medications, phenobarbital and Lamictal.

According to The Epilepsy Foundation, surgery to remove injured brain tissue and control seizures requires thorough evaluation, including the recording of a seizure with EEG and neuropsychological testing to determine if someone is a good candidate for surgery. Such testing can help a physician determine if there is a part of the person's brain tissue good for nothing but generating seizure activity.

Another, more debated type of treatment is the ketogenic diet, a special high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet used mainly in children and sometimes prescribed as a treatment option for those with intractable epilepsy. The diet results in ketosis, a condition in which excessive amounts of ketones (substances chemically akin to acetone) are produced, resulting in an anti-epileptic effect.

DeLorenzo says much is still unknown about the diet: "How does it work? How well does it work compared to current medications? It is a very tough diet to go on; if you draw blood [from someone on the diet] there is so much fat the blood looks creamy. It does: work well for some people, but if it worked well for everyone [with epilepsy], everyone would be on it."

What the Future Holds

Van Hazerbeke says The Epilepsy Foundation is excited about efforts in the area of genetic research.

"It is very likely that we will find that a lot of epilepsy has a genetic basis--not necessarily that a person has inherited it but that within their physiology there has been a new mutation," he explains. "In July 1998 the British journal Nature published an article based on finding a gene in a mouse model for a common form of epilepsy, absence or petit mal epilepsy. It's called the stargazer gene--after the mouse's name, Stargazer--and the study is considered a breakthrough."

Van Hazerbeke says the new study may lead to a test to determine if an individual has a particular form of epilepsy and that may eventually lead to reversal, prevention, or a cure.

Approximately 150,000 new cases of epilepsy are diagnosed annually. Although few people actually die during seizures, the sheer numbers of people battling the disorder, the high costs associated with the condition, and lifestyle limitations make advocates determined to keep looking for answers.

"The biggest problem is that epilepsy is still considered [by some] to be a condition involved with mental illness or demonic possession," says DeLorenzo. Although things are better today, he explains, many epilepsy sufferers still feel stigmatized by their condition. He adds that a big misconception about epilepsy is that the general public feels it's a simple, easy-to-control problem instead of a complex disorder.

Although many experts say full or partial control of epileptic seizures can be achieved via modern treatment methods in 85 percent of cases, DeLorenzo estimates that only about half of all people with epilepsy are well-controlled.

"This represents a major public health problem that needs to be addressed. Well-controlled patients can lead a normal life," he emphasizes.

DeLorenzo is developing a database of epilepsy patients at MCV Hospitals to help develop drug protocols. In addition, under an NIH grant, DeLorenzo has determined that in several animal models the ability to develop epilepsy is calcium-related.

"If this is also true for humans, drugs can be developed to block this [effect]," he explains.

FDA's Katz notes there are currently a number of epilepsy drugs in development and there is a great deal of research on the basic mechanisms of the disorder.

"That's good," he says, "because the better you understand an illness, the more likely you are to create treatments that are effective in treatment and prevention."

More on Epilepsy

RELATED ARTICLE: If You Witness a Seizure

If you're present when someone has a seizure, keep calm and help the person to the floor, loosening any clothing around the neck. Remove any sharp objects that could cause injury and turn the person on one side so saliva can flow from the mouth. Putting a cushion or a folded coat under the head for a pillow is fine, but don't put anything in the person's mouth.

Some people will sleep or want to rest following a seizure; they may be confused and need help getting home. Obviously parents should be contacted if a child has a seizure.

If you know that the person having a seizure has epilepsy, an ambulance is probably unnecessary unless the seizure is prolonged (more than five minutes). If you don't know, or if the person is diabetic, ill or pregnant, get help immediately.

--A.H.

RELATED ARTICLE: Strict for Felbatol

The drug Felbatol (felbamate) caused much excitement when it was first approved in 1993, says Russell Katz, M.D., deputy director of FDA's division of neuropharmacological drug products. But a year later, reported cases of bone marrow suppression and liver problems caused FDA to take quick action.

"Felbamate was approved for use as an add-on drug or in monotherapy, and prior to approval it seemed to have few significant side effects. People began to use it quite a bit," Katz recalls.

After the drug had been on the market a year, FDA began to receive reports that patients were developing aplastic anemia, a potentially life-threatening disorder in which the bone marrow essentially shuts down and stops making blood cells. Some of the users required bone marrow transplants, and there were some deaths.

"We had seen nothing prior to approval indicating this drug would do this," Katz says. "We had a very serious side effect. There was a low incidence rate, in terms of overall numbers, but here's the problem: say 1 in 5,000 people taking a drug gets an adverse [reaction]. For the typical physician, that is a low rate; he or she may not have a patient that experiences that [reaction]. But if 1 million people are taking the drug and 1 in 5,000 have adverse effects, that is a lot of cases from the public health perspective."

FDA met with its advisory committee, an outside review panel of experts, and the decision was made to keep felbamate on the market but in a severely restricted capacity.

"The professional labeling has huge warnings on it that say felbamate is not indicated as a first-line epileptic treatment; it's only for those whose epilepsy is so severe that a substantial risk of aplastic anemia or liver failure is deemed acceptable in light of the benefits conferred by its use," Katz explains. "The patient package insert includes an information consent form in bold letters because now the company requires doctors to get informed consent from patients to use it, which is very unusual. Because it is a potentially extremely dangerous drug, usage has gone down considerably as a result."

--A.H.

Audrey Hingley is a writer in Mechanicsville, Va.

COPYRIGHT 1999 U.S. Government Printing Office

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group