Finasteride has been associated with the development of gynecomastia. Although cytoplasmic vacuolization has been noted in prostatic epithelium in men taking this drug, we found no documentation of the cytologic changes in finasteride-associated gynecomastia. We present the case of a 53-year-old man who developed unilateral gynecomastia following finasteride therapy for alopecia. A fineneedle aspiration biopsy of the mass was diagnosed as adenocarcinoma on the basis of nuclear atypia and particularly because of cytoplasmic vacuolization. Subsequent excisional biopsy revealed benign gynecomastia with no evidence of malignant change. The ductal epithelium did exhibit cytoplasmic vacuolization similar to that described in the prostate following finasteride therapy. We believe this is the first reported case documenting the cytologic changes seen in gynecomastia secondary to finasteride therapy. Cytoplasmic vacuolization in this setting should not be considered evidence of malignancy in men with gynecomastia. As with gynecomastia in general, extreme caution should be used before rendering a cytologic diagnosis of malignancy.

Gynecomastia is a known complication of a variety of conditions characterized by hormonal imbalance. Several drugs, including chemotherapeutic agents used to treat prostate and other cancers, have been associated with gynecomastia.1-3 The drug finasteride (Proscar), used to treat benign prostatic hypertrophy and alopecia, has also been documented to cause gynecomastia.4 Typically, the gynecomastia resolves after the drug is discontinued:A Rarely, ductal or lobular carcinomas of the male breast have been documented to arise in these cases.5 The Cytology of these cancers is similar to that seen in females. However, to date there has been no description of any cytologic changes of gynecomastia induced by finasteride.

We present the case of a 53-year-old man who developed unilateral gynecomastia while taking finasteride for alopecia. A fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the mass was initially diagnosed as adenocarcinoma. Subsequent excisional biopsy revealed gynecomastia without evidence of carcinoma. This case represents a potential pitfall when evaluating a male breast mass in the setting of finasteride therapy. We believe this case report also represents the first description of the cytologic changes associated with finasteride therapy.

REPORT OF A CASE

The patient was a 53-year-old physician treated for alopecia with the drug finasteride (1 mg per day). After 10 weeks of therapy, he developed a 3-cw-diameter mass in the right breast, which was clinically believed to be gynecomastia. A fine-needle aspiration biopsy was performed using a 22-gauge needle and a 10-mL syringe; the aspirated material was placed into 0.9% sodium chloride solution. Cytospin and filter preparations were made and stained with the Papanicolaou method. A diagnosis of adenocarcinoma was rendered. The patient's finasteride therapy was discontinued after this diagnosis. Given the uncertainty introduced by the patient's medication history, an excisional biopsy was performed. The entire mass was excised and submitted for histologic examination: The mass revealed gynecomastia with no evidence of ductal or lobular carcinoma.

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

The aspirated material was cellular and exhibited a slightly bloody background. The epithelial cells exhibited modest nuclear atypia, including an increased nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, a slightly irregular nuclear outline, and an absence of myoepithelial cells. Of particular concern was the presence of vacuolated cytoplasm in a minority of cells (Figure 1). The nuclear contours of some of these vacuolated cells were also slightly irregular. Based on these features, a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma was rendered. The vacuolated cells in particular raised the prospect of a lobular carcinoma; however, no necrosis, clusters of cells infiltrating fat lobules, or significant pleomorphism was noted.

GROSS AND HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS

The excised mass measured 3.5 X 3.2 X 2.1 cm. Serial sectioning revealed homogeneous white-yellow tissue with no gross evidence of necrosis. The parenchyma was fibrous but not gritty. The gross impression was that of gynecomastia: Microscopic examination revealed classic features of gynecomastia. In addition to epithelial hyperplasia and its associated modest nuclear atypia, squamous metaplasia and cells with vacuolated cytoplasm were noted (Figure 2). There was neither an infiltrating carcinoma nor sufficient atypia for a diagnosis of carcinoma in situ.

COMMENT

Gynecomastia has a known association with breast carcinoma in males. A recent review of male breast carcinomas showed gynecomastia was present in 70 (37%) of 27 invasive carcinomas.6 Of note, medications known or suspected to cause gynecomastia were found in a similar percentage of patients presenting with either gynecomastia or carcinoma. Thus, medication history should not influence the decision to biopsy unilateral breast masses. While far less common in males, breast cancer has a worse prognosis in males than in females. However, when matched for age and stage, there are no differences in survival rates. This may be explained in part by the more advanced stages of disease at the time of presentation in men.

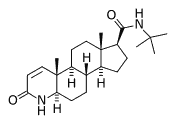

Finasteride is a competitive inhibitor pf steroid 5-alpha-reductase, an enzyme that converts testosterone to the potent androgen, 5-alpha-dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Finasteride exhibits 100-fold selectivity for the type II isozyme, found mainly in prostate tissue, seminal vesicles, epididymes, hair follicles, and liver. The type II isozyme of steroid 5-alpha-reductase accounts for about two thirds of circulating DHT. The therapeutic effects of finasteride, such as regression of enlarged prostatic tissue and stimulation of hair follicles, are the result of decreased serum and tissue DHT levels. Finasteride does not bind to androgen receptors.8 Finasteride was approved in 1992 for the treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy under the trade name Proscar. The same drug was approved in 1997 for the treatment of alopecia under the trade name Propecia. The Food and Drug Administration and case reports in the literature have documented an association between finasteride and gynecomastia.4 Additionally, one case report suggested finasteride can cause cytoplasmic vacuolization in prostatic epithelium.9 Previously reported cases of gynecomastia arising secondary to finasteride therapy leave generally been treated by discontinuation of the drug, resulting in resolution of the mass. No biopsies were mentioned in these reports.

The presence of vacuolated cells in the case presented here parallels the vacuolated cells described in the prostate.9 In the setting of gynecomastia, these vacuolated cells present a diagnostic dilemma. A review of cytology and surgical pathology textbooks failed to reveal cytoplasmic vacuolization described as a normal finding in gynecomastia.1-3,10 Vacuolization is associated with chemotherapeutic agents and a variety of different medications.1-3 Such vacuolated cells, especially in a background of relatively atypical and monotonous cells, can be found in lobular carcinoma. While male breast carcinoma is exceedingly unusual; we found 2 documented instances of adenocarcinoma, including a lobular carcinoma, arising in association with finasteride therapy.5

Various cytology texts have recommended unequivocal, if not obvious, evidence of malignancy before diagnosing carcinoma in clinical gynecomastia.10 This advice seems all the more valuable when the patient is being treated with finasteride. As with any diagnosis based on fine-needle aspiration biopsy, a conservative opinion is prudent if the aspiration biopsy is the sole basis of radical surgery or other morbid therapy. We recommend that vacuolated cells on aspirate smears not be considered evidence of malignancy in a patient with a history of therapy with finasteride or other newly developed medications. Rather, we suggest a diagnosis of epithelial atypia and recommend an excisional biopsy.

References

1. De May RM. The Art and Science of Cytopathology. Chicago, Ill: ASCP Press; 1996:890-891.

2. Rosen PP. Rosen's Breast Pathology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:611-617.

3. Tavassoli FA. Pathology of the Breast. New York, NY: Elsevier; 1992:639-- 640.

4. Wilton L, Pearce G, Edet E, Freemantle S, Stephens MDB Mann RD. The safety of finasteride used in bengin prostatic hypertrophy: a non-interventional observational cohort study in14772 patients. Br J Urol. 1996;78:379-384.

5. Green L, Wysowski DK, Fourcory JL. Gynecomastia and breast cancer during finasteride therapy [letter]. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:823.

6. Joshi MG, Lee AKC, Loda M, Camus Mg, Heatley GJ, Hughes KS. Male breast carcinoma: an evalution of prognostic factors contributing to a poorer outcome. Cancer. 1996;77:490-498.

7. O'Hanlon DM, Kent P, Kerin MJ, Given HF. Unilateral breast masses in men over 40: a diagostic dilemma. Am J Surg. 1995;170:24-26.

8. Propecia (finasteride) [package insert]. West Point, Pa: Merk and Co Inc; 1996.

9. Civantos F, Soloway MS, Pinto JE. Histopathologic effects of androgen deprivation in prostatic cancer. Semin Urol Oncol. 1996;142(2 suppl 2):22-31.

10. Silverman JS. Breast. In: Bibbo M, ed. Comprehensive Cytopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 1997:749.

Accepted for publication July 22, 1999.

From the Departments of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine (Drs Zimmerman and Fogt), Surgery (Dr Cronin), and Pharmacy (Dr Lynch), Presbyterian Medical Center; University of Pennsylvania Health System, Philadelphia, Pa.

Reprints: Robert L. Zimmerman, MD, Department of Pathology, W-- 547, Presbyterian Medical Center, 39th and Market Streets, Philadelphia, PA 15104.

Copyright College of American Pathologists Apr 2000

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved