Urinary incontinence occurs in all age groups but is most common among older persons. Recent large-scale surveys have found that as many as one-third of persons over age 60 occasionally experience some involuntary loss of urine.(1) Severe incontinence, occurring regularly or most of the time, affects approximately one out of every 20 elderly persons.(2) One study(3) showed that among persons over 65 years of age living in the community or in institutions, incontinence develops in approximately 10 percent of persons within the next three years.

About half of persons with incontinence do not seek medical attention, believing that the condition is an inescapable or untreatable part of the aging process. Those who seek medical evaluation most frequently consult family physicians or urologists.(10) Other specialists, such as gynecologists, are consulted less often. Thus, family physicians have a central role in the diagnosis and management of urinary incontinence.

When evaluating patients with urinary incontinence, the physician should first search for transient or reversible causes. The principal reversible causes of incontinence can be remembered with the mnemonic DIAPPERS (Table 1). Reversible or treatable causes can be identified in more than half of older persons with urinary incontinence.(6)

When a reversible cause of incontinence cannot be identified, it is called permanent or irreversible incontinence. Even in irreversible incontinence, some degree of improvement can be achieved in most patients with a variety of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches.(7) This article focuses on nonpharmacologic treatments for urinary incontinence. Types of Urinary Incontinence The causes of permanent urinary incontinence are generally grouped into four categories: uninhibited detrusor contractions, overflow incontinence, sphincter incompetence and mixed incontinence. Each has its own basic pathophysiology, which must be understood if therapy is to be administered rationally.

UNINHIBITED DETRUSOR CONTRACTIONS

Uninhibited detrusor contractions are the most common cause of permanent urinary incontinence. This mechanism is the cause of permanent urinary incontinence in 50 to 70 percent of persons, depending on the population studied.(5) For practical clinical purposes, detrusor hyperreflexial detrusor instability, detrusor hyperactivity, urge incontinence and uninhibited bladder are synonymous terms for uninhibited detrusor contractions.

In this type of incontinence, the detrusor muscle of the urinary bladder contracts at inappropriately small bladder volumes, that is, before the bladder is completely full. The contractions cannot be consciously inhibited by the patient. The underlying cause is usually decreased function of cerebral centers that inhibit urination. This type of incontinence commonly occurs with dementia or other neurologic disorders, but also may occur without obvious neurologic disease.

OVERFLOW INCONTINENCE

Overflow incontinence is responsible for less than one-third of cases of permanent incontinence. It occurs when the bladder does not empty properly. The bladder distends and fills to capacity, until urine leaks by overflow.

Overflow incontinence occurs in two situations. The first is diminution or loss of contractile activity of the detrusor muscle-for example, when demyelinating disease or neuropathy impairs innervation of the bladder detrusor. The second situation is obstruction of the bladder outlet from conditions such as prostate enlargement, urethral stricture or uninhibited contraction of the urethral sphincter (e.g., detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia).

SPHINCTER INCOMPETENCE

Sphincter incompetence refers to inability of the urinary sphincter to prevent leakage of urine at undesired times. The most common type of sphincter incompetence is female stress incontinence. The term stress incontinence refers to a syndrome in which episodes of incontinence occur in response to the stress of increased intra-abdominal pressure, typically associated with coughing, laughing, running and so forth. It should be emphasized that stress incontinence is not a final diagnosis. Stress incontinence may sometimes be due to uninhibited detrusor contractions rather than sphincter incompetence.

Although stress incontinence is often reversible, it is not reversible in all cases. Therefore, it is potentially permanent in some persons. Up to 10 percent of cases are due to an incompetent sphincter, which generally is related to neuropathic or postoperative sphincter denervation.

MIXED INCONTINENCE

In clinical practice, patients may have incontinence due to a combination of causes (uninhibited detrusor contractions, overflow incontinence and/or sphincter incompetence). These patients have mixed incontinence. At least 10 to 15 percent of incontinent patients have mixed causes of incontinence.(8)

In the evaluation of urinary incontinence systematic assessment strategy must be used so that reversible causes of incontinence are not overlooked. The approach to the evaluation of older patients with urinary incontinence has recently been described in two articles by Ouslander and colleagues.(9,10) Pharmacologic Therapy

Pharmaceutical agents are widely used to treat urinary incontinence (Table 2). These medications have two primary purposes: 1) to decrease bladder contractility in patients with uninhibited detrusor contractions and (2) to increase bladder outlet resistance in patients with sphincter incompetence.(11)

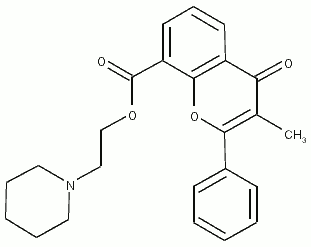

Drugs used to decrease uninhibited detrusor contractions include anticholinergics, musculotropic relaxants (e.g., oxybutynin [ Ditropan ], flavoxate [ Urispas ]), calcium antagonists, prostaglandin inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants and beta-adrenergic agonists. Agents in each of these categories have in vitro and in vivo activity that decreases the contractility of bladder smooth muscle.

Drugs used to increase outlet resistance include alpha-adrenergic agonists, which contract the urethral sphincter (e.g., ephedrine, pseudoephedrine), beta-adrenergic antagonists (e.g., propranolol [Inderall), which inhibit relaxation of the sphincter, and both topical and orally administered estrogens, which increase the sensitivity of the urethra to alpha-adrenergic stimulation. It is of ten appropriate to initiate a trial of drug therapy in patients with sphincter incompetence. Problems with Pharmacologic Treatment

Using medications to treat incontinence is appealing to both physicians and patients because of its apparent simplicity. However, when prescribing drugs for urinary incontinence, physicians should always keep two principal concerns in mind. First, potential side effects (Table 2) and interactions with other drugs must be considered. These are particular problems in frail elderly patients and in patients already taking multiple drugs.

A second concern relates to the efficacy of drug therapy for urinary incontinence. While many studies have shown that drug therapy is effective, other well-controlled and carefully executed studies have concluded otherwise. For example, well-designed studies have shown that flavoxate is not effective in the treatment of uninhibited detrusor contractions(12) and that alpha-adrenergic agents are not effective in the treatment of stress incontinence. In addition, some studies that have demonstrated efficacy of pharmaceutical agents have not included elderly patients in the study population.

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

Because of concerns about drug side effects and the lack of consistent evidence of benefit from pharmacologic therapy, interest in the use of nonpharmacologic interventions has been growing. Nonpharmacologic therapies are appealing because of their inherent lack of adverse effects, their low cost and evidence that they are effective for the treatment of incontinence. Many experts recommend nonpharmacologic intervention as first line therapy for incontinence, either before or as an adjunct to drug therapy.

Nonpharmacologic therapies recommended for the treatment of urinary incontinence can be grouped into several broad categories, including (1) scheduling regimens, (2) muscle exercises, (3) biofeedback training, (4) electrical stimulation and (5) devices and surgical treatments.

Devices used in the management of incontinence (catheters, incontinence underpants, pessaries, etc.) have been reviewed elsewhere(15-17) and will not be discussed in this article. Surgical approaches (prostate operations, repair for stress incontinence and implantation of artificial urinary sphincters"') are also beyond the scope of this review.

SCHEDULING REGIMENS

Four behavioral therapies, known as scheduling regimens," are useful for the management of uninhibited detrusor contractions.(19) The regimens differ from one another on the basis of changes in the interval between voiding (Table 3). Surprisingly simple in concept, several scheduling regimens have proved effective for the management of uninhibited detrusor contractions. The efficacy of scheduling regimens can equal or exceed that of drug therapy.

Bladder Training. Bladder training, also known as bladder drill, bladder discipline and bladder reeducation, is the most widely studied scheduling regimen.

In bladder training, the patient gradually lengthens the interval between voiding. The initial voiding interval is prescribed by the clinician, and is adjusted according to the severity of incontinence. For severe cases, an initial voiding interval of 30 to 60 minutes is typically used. The patient progressively lengthens the voiding interval until it reaches three to four hours.(10) No specific voiding schedule is used at night, but the patient is instructed to void immediately before and after sleep.

In one variation of bladder training, the patient must adhere to a prescribed lengthening of the voiding interval, even if incontinence occurs. The other variation involves self-scheduled lengthening of the voiding interval; the patient tries to adhere to the prescribed voiding interval but may use the toilet, if necessary, before the prescribed interval elapses.

Clinical trials(21-23) have shown that bladder training is more effective than no treatment in reducing incontinent episodes in women with uninhibited detrusor contractions. Cure rates (i.e., control of incontinence) have ranged from 44 percent to over 90 percent; the reasons for variations in cure rates are not known. The technique has also been found to be superior to drug treatment in controlled trials in women aged 27 to 79 years with uninhibited detrusor contractions.

Habit Training. In contrast to bladder training, in which the voiding interval progressively increases, the voiding interval in habit training may be either increased or decreased as necessary. In habit training, the patient is given a prescribed voiding schedule and is encouraged to delay voiding until the scheduled time. The typical voiding interval in habit training is two hours. If the patient is unable to postpone voiding for the recommended interval, a new, shorter voiding interval can be established.

A recent trial(24) evaluated habit training (with a two-hour interval) and oxybutynin treatment in functionally disabled nursing home patients with uninhibited detrusor contractions. All patients were checked for wetness every two hours. After two weeks of habit training, the frequency of "wet checks" among the residents fell from 43 percent to 32 percent. The subsequent addition of oxybutynin to the regimen did not further decrease the number of incontinent episodes. Although the sample size in this study was small (15 patients), the results suggest that habit training may be as effective as medications for controlling incontinence related to uninhibited detrusor contractions.

Timed Voiding. In timed voiding, a fixed voiding schedule (e.g., every two hours) is given to the patient. The voiding schedule remains unchanged regardless of the patient's success or failure at controlling voiding. Timed voiding is commonly used in nursing homes.(25) No controlled trials of timed voiding have been reported, and some patients may find the technique unacceptable.

Prompted Voiding. In prompted voiding, the patient is asked at regular intervals (e.g., hourly) about the need to void. If the response is affirmative, access to the toilet is provided. The interval selected may vary with the needs of the patient and the institution.

Prompted voiding is widely used for cognitively or mobility impaired patients in nursing homes and appears to be effective. In one study of nursing home patients with incontinence and cognitive impairment (mean Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination score = 7.9), hourly prompting between morning and bedtime reduced the frequency of wet checks by 40 percent. In this study, patients with the highest baseline frequency of incontinence were the most likely to improve with prompted voiding.

MUSCLE EXERCISES

Pelvic (floor) muscle exercises, often called Kegel(27) exercises, are frequently recommended for the treatment of stress incontinence due to urinary sphincter incompetence. Pelvic muscle exercises are a learned technique of simultaneously contracting and relaxing the perivaginal, periurethral and perianal muscles. Pelvic muscle exercise increases urethral resistance by increasing periurethral muscle tension.

It is difficult to evaluate research on the effectiveness of pelvic muscle exercises in eliminating stress incontinence because (1) exercise protocols differ in many studies and (2) compliance with the recommended exercise routines cannot be accurately assessed. Nonetheless, most research evaluating pelvic muscle exercise suggests that it is effective in reducing episodes of urinary leakage in women with stress incontinence. Cure rates range from 31 to 73 percent, and success rates (cure or improvement) range from 43 to 96 percent.(28-30) No complications have been reported, and worsening of incontinence after pelvic muscle exercises has only rarely been reported.(31) It should be noted, however, that surgical treatment of sphincter incompetence is probably more effective than pelvic muscle exercise in alleviating incontinence.(32)

Pelvic muscle exercise routines recommended in the literature vary, and no regimen is clearly superior. The most commonly recommended duration for each muscle contraction is 10 seconds. The number of recommended contractions per day varies from 15 to 160, with a typical number being 50 to 80 contractions per day. It is often recommended that the exercises be performed in one session, but other recommendations include dividing the sessions into 30-minute, one-hour or two-hour periods throughout the day.(33) An example of a regimen that could be recommended to patients is 20 contractions (held 10 seconds) four times per day.

BIOFEEDBACK

Biofeedback is a technique that detects a physiologic response and instantly demonstrates to the patient that the response has occurred. Biofeedback equipment can detect detrusor contractions and urinary sphincter contractions. For patients who have lost the ability to inhibit detrusor contractions or to contract the urethral sphincter, biofeedback can potentially help them to relearn and regain control of those functions.

Thus, biofeedback methods are potentially useful in patients with uninhibited detrusor contractions and stress incontinence due to sphincter incompetence. Frequently, biofeedback is used as an adjunct to other nonpharmacologic modalities. For example, biofeedback can be used on a weekly basis for one to two months, at the time that scheduling regimens or pelvic exercise is instituted, to help patients gain control of their detrusor or sphincter muscles.

Much of the reported experience with biofeedback for urinary incontinence comes from physical medicine specialists. Thus, physiatrists may be useful consultants in the management of patients with urinary incontinence. Patients generally must have full cognitive capabilities.

Uninhibited Detrusor Contractions. Biofeedback techniques for the management of uninhibited detrusor contractions involve simultaneous use of a transurethral bladder catheter and a rectal pressure monitor. The bladder catheter measures intravesical pressure increases, which are indicative of bladder contractions. The intrarectal monitor measures and subtracts out increases in intra-abdominal pressure that might otherwise confound the bladder pressure measurements. Patients view polygraphic tracings of their intrabladder pressure (i.e., contractions) and learn to sense and, subsequently, inhibit those contractions.

The role of biofeedback in the management of uninhibited detrusor contractions has not been extensively evaluated. In one uncontrolled study, 34 an 88 percent reduction in incontinence episodes was achieved in a group of elderly men who participated in a single half-day biofeedback training session.

In another controlled study, 35 biofeedback plus bladder training was compared with bladder training alone. Patients who received biofeedback plus bladder training had a more rapid improvement in incontinence than patients who received five weeks of treatment and on subsequent follow-up visits, both groups had achieved an identical degree of bladder control.

Given the expense and logistical difficulties involved in providing biofeedback treatment for uninhibited detrusor contractions, evidence of efficacy is not adequate to support routine use of this therapeutic modality.

Stress Incontinence. Biofeedback modalities for stress incontinence are considerably less technology intensive. Patients can receive feedback about contraction of their pelvic floor muscles by observing the interruption of their urinary stream or by palpating these muscles through vaginal wallmucosa.(36) More complex equipment, such as an intravaginal perineometer probe, is also available for measuring contraction of the pelvic floor muscles.

Research suggests that biofeedback is an effective adjunct to the use of pelvic muscle exercises. Several studies(37,38) have shown that improvement and/or cure rates of up to 90 percent can be obtained when biofeedback training is used with exercises. Improvement and/or cure rates in nonbiofeedback (exercise only) control groups were only about 50 percent. It is not clear whether use of a perineometer offers an advantage over more simple methods of biofeedback.

ELECTRICAL STIMULATION

Although electrical stimulation therapy is not widely used in the United States, interest in this modality for the control of urinary incontinence is increasing. Electrical stimulation therapy, administered with devices similar to those used for transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), is available in selected centers throughout the United States. If research continues to demonstrate efficacy of electrical therapy, it will be a useful (though potentially expensive) alternative to standard interventions.

Electrodes are implanted through the S3 neural foramen and lie in contact with sacral nerve roots. The electrode wire is then tunneled under the skin and connected to a stimulator imbedded in the anterior abdominal wall. The patient can control stimulation of the nerve roots, which simultaneously causes detrusor muscle relaxation and urethral sphincter contraction. Electrical stimulation therapy has been used in patients with refractory uninhibited detrusor contractions or postprostatectomy incontinence.(39)

Early experience with electrical therapy, using older techniques, was disappointing. A more recent trial using the newer technique has produced cure or improvement in up to 70 percent of patients with uninhibited detrusor contractions and 40 percent of patients with postprostatectomy incontinence.(39) Current research indicates that long-term electrical stimulation is safe, and no evidence of refractoriness to treatment has emerged, even after treatment over a period of years.

REFERENCES

1 .Diokno AC, Brock BM, Brown MB, Herzog

AR. Prevalence of urinary incontinence and

other urological symptoms in the noninstitutionalized

elderly. J Urol 1986;136:1022-5.

2 .Vetter Nj, Jones DA, Victor CR. Urinary incontinence

in the elderly at home. Lancet 1981;

2(8258):1275-7.

3 .Campbell Aj, Reinken J, McCosh L. Incontinence

in the elderly: prevalence and prognosis.

Age Ageing 1985; 14(2):65-70.

4 .Jeter KF, Wagner DB. Incontinence in the

American home. A survey of 36,500 people. J

Am Geriatr Soc 1990;38:379-83.

5. Resnick NM. Initial evaluation of the incontinent

patient. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990;38:311-6.

6. Brocklehurst JC. Urinary incontinence in old

age: helping the general practitioner to make a

diagnosis. Gerontology 1990; 36(Suppl 2):3-7.

7. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development

Conference on Urinary Inconti - nence in Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990;38:

263-386.

8. Diokno AC, Wells Tj, Brink CA. Urinary

incontinence in elderly women: urodynamic

evaluation. J Am Geriatr Soc 1987;35:940-6.

9. Ouslander J, Leach G, Staskin D, et al. Prospective

evaluation of an assessment strategy

for geriatric urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr

Soc 1989;37:715-24.

10. Ouslander JG, Leach GE, Staskin DR. Simplified

tests of lower urinary tract function in

the evaluation of geriatric urinary incontinence.

J Am Geriatr Soc 1989;37:706-14.

11. Wein Aj. Pharmacologic treatment of incontinence.

J Am Geriatr Soc 1990;38:317-25.

12. Briggs RS, Castleden CM, Asher MJ. The

effect of flavoxate on uninhibited detrusor

contractions and urinary incontinence in the

elderly. J Urol 1980;123:665-6.

13. Obrink A, Bunne G. The effect of alpha-adrenergic

stimulation in stress incontinence. Scand J

Urol Nephrol 1978; 12:205-g.

14. Burgio KL. Behavioral training for stress and

urge incontinence in the community. Gerontology

1990;36(Suppl 2):27-34.

15. Weiss BD. Chronic indwelling bladder catheterization.

Am Fam Physician 1984;30(3):

161-6.

16. Brink CA. Absorbent pads, garments, and

management strategies. J Am Geriatr Soc

1990;38:368-73.

17. Warren JW. Urine-collection devices for use in

adults with urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr

Soc 1990;38:364-7.

18. Small MP. The Rosen incontinence procedure:

a new artificial urinary sphincter for the

management of urinary incontinence. J Urol

1980;123:507-11.

19. Hadley EC. Bladder training and related therapies

for urinary incontinence in older people.

JAMA 1986;256:372-9.

20. Fantl JA, Wyman JF, Harkins SK Hadley EC.

Bladder training in the management of lower

urinary tract dysfunction in women. A review.

J Am Geriatr Soc 1990;38:329-32.

21. Pengelly AW, Booth CM. A prospective trial

of bladder training as treatment for detrusor

instability. Br J Urol 1980;52:463-6.

22. Elder DD, Stephenson TP. An assessment of

the Frewen regimen in the treatment of detrusor

dysfunction in females. Br J Urol 1980;

52:467-71.

23. Jarvis GJ, Millar DR. Controlled trial of bladder

drill for detrusor instability. Br Med J

1980;281:1322-3.

24. Ouslander JG, Blaustein J, Connor A, Pitt A.

Habit training and oxybutynin for incontinence

in nursing home patients: a placebo-controlled

trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988;36:40-6.

25. Ouslander JG, Fowler E. Management of urinary

incontinence in Veterans Administration

nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 1985;33:

33-40.

26. Schnelle JF. Treatment of urinary incontinence

in nursing home patients by prompted voiding.

J Am Geriatr Soc 1990;38:356-60.

27. Kegel A. Progressive resistance exercises in

the functional restoration of the perineal muscles.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 1948;56:238-48.

28. Benvenuti F, Caputo GM, Bandinelli S, Mayer

F, Biagini C, Sommavilla A. Reeducative treatment

of female genuine stress incontinence.

Am J Phys Med 1987;66(4):155-68.

29. Stoddart GD. Research project into the effect

of pelvic floor exercises on genuine stress incontinence.

Physiotherapy 1983;69:148-9.

30. Mohr JA, Rogers J Jr, Brown TN, Starkweather

G. Stress urinary incontinence: a simple and

practical approach to diagnosis and treatment.

J Am Geriatr Soc 1983;31:476-8.

31. Castleden CM, Duffin HM, Mitchell EP. The

effect of physiotherapy on stress incontinence.

Age Ageing 1984; 13(4):235-7.

32. Klarskov P, Belving D, Bischoff N, et al. Pelvic

floor exercise versus surgery for female

urinary stress incontinence. Urol Int 1986;41:

129-32.

33. Wells TJ. Pelvic (floor) muscle exercise. J Am

Geriatr Soc 1990;38:333-7.

34. Burgio KL, Whitehead WE, Engel BT. Urinary

incontinence in the elderly. Bladder-sphincter

biofeedback and toileting skills training. Ann

Intern Med 1985; 103:507-15.

35. Burton JR, Pearce KL, Burgio KL, Engel BT,

Whitehead WE. Behavioral training for urinary

incontinence in elderly ambulatory patients.

J Am Geriatr Soc 1988;36:693-8.

36. Burgio KL, Engel BT. Biofeedback-assisted

behavioral training for elderly men and women.

J Am Geriatr Soc 1990;38:338-40.

37. Shepherd AM, Montgomery E, Anderson RS.

Treatment of genuine stress incontinence with

a new perineometer. Physiotherapy 1983;69:

113.

38. Burgio KL, Robinson JC, Engel BT. The role of

biofeedback in Kegel exercise training for

stress urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1986;154:58-64.

39. Tanagho EA. Electrical stimulation. J Am

Geriatr Soc 1990;38:352-5.

COPYRIGHT 1991 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group