Physicians painful often encounter patients who present with painful conditions such as lacerations, fractures, and dislocations that require the use of interventions. Furthermore, certain nonpainful procedures, such as computed tomography in a small child, may require the use of anxiolytic agents or behavioral control. The phrase procedural sedation refers to the techniques of managing a patient's pain and anxiety to facilitate appropriate medical care in a safe, effective, and humane fashion.

Definitions of procedural sedation vary. (1-4) Older terminology that includes the phrase conscious sedation should be abandoned. Procedural sedation and analgesia (PSAA) is a more accurate and appropriate description. (5)

PSAA produces a suppressed level of consciousness that is adequate to allow the administration of painful or unpleasant diagnostic or therapeutic maneuvers in a way that minimizes patient awareness, discomfort, and memory, while attempting to preserve spontaneous respiration and airway-protective reflexes. PSAA should be viewed as a continuum ranging from light to deep sedation, with the depth of sedation easily titrated by selective administration of sedatives and analgesics. Because of the range of sedation, it cannot be assumed that spontaneous ventilation will occur at each level.

PSAA can be performed as an outpatient procedure in the urgent care clinic or in the physician's office. Because patients are given medications that suppress consciousness, the physician must be experienced in managing potential complications of the procedure, including vomiting, respiratory depression, hypoxia, hypotension, and cardiac arrest. The most serious complication is respiratory failure from airway obstruction or hypoventilation. Advanced airway-management skills are a mandatory prerequisite for performing these techniques.

General Approach to Procedural Sedation

Many groups have published recommendations for the performance of PSAA. (1-4,6) The most important recommendation involves the person performing the procedure. This person must have an understanding of the medications administered, the ability to monitor the patient's response to the medications given, and the skills necessary to intervene in managing all potential complications. Failure to meet this recommendation should be viewed as an absolute contraindication to PSAA.

The next step is appropriate patient selection. Absolute contraindications are uncommon, but the physician should consider comorbid illness or injury, the ability to manage the patient's airway, and previous problems with PSAA. Patients with significant comorbid cardiac, hemodynamic, or respiratory compromise should be approached with caution, as should patients who may be difficult to intubate or manually ventilate.

Although fasting before PSAA commonly is recommended, (2,3) there are insufficient data to determine whether fasting improves outcomes. The American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends a two-hour fast for clear liquids and a six-hour fast for food. (3)

Recent oral intake is not an absolute contraindication to PSAA, but logic suggests that patients with prolonged fasting are less likely to aspirate than patients who have just eaten. (1,4) The urgency of the procedure, the time of the last meal, and the likelihood of significant aspiration must all be taken into account when deciding whether a particular patient would be a good candidate for PSAA. (3,7)

Published guidelines (1-3) recommend cardiac and pulse-oximetry monitoring for patients undergoing PSAA. The patient should be monitored fully from before the medications are administered until all sedation has worn off and the patient has resumed his or her baseline level of function, with frequent bedside recording of the patient's status and vital signs. (1-4) This should be done by an experienced health care professional, often a nurse, whose only job is to monitor the patient until recovery is complete.

Required equipment includes cardiac and pulse-oximetry monitors; oxygen and appropriate delivery systems, ranging from nasal cannula to high-flow oxygen mask (nonrebreather); bag-valve mask; suction; appropriately sized oral airways and endotracheal tubes; laryngoscope with appropriate blades; and medications and equipment for cardiac resuscitation. All of the equipment should be at the bedside before the first dose of sedative is given.

Agents for Procedural Sedation

Many medications are available to facilitate PSAA. The ideal agent possesses analgesic and amnestic properties, has rapid onset and short duration of action, is safe, and allows rapid recovery and discharge. Recent trends have favored the use of medications such as etomidate and ketamine, while familiar agents such as fentanyl and mid-azolam continue to be used widely. Common indications for the use of PSAA are listed in Table 1.

ETOMIDATE

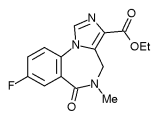

Etomidate is an imidazole derivative that possesses little analgesic effect. Intravenous use produces a hypnotic state, usually within one minute. The duration of effect is brief, lasting three to five minutes at standard dosages. Etomidate is metabolized rapidly by the liver, and the duration of effect may be longer in patients with liver failure. (8)

The only contraindication to etomidate is hypersensitivity to the medication, but caution should be taken during pregnancy (etomidate is a pregnancy category C drug), and the general precautions regarding procedural sedation and patient selection also should be considered.

Adverse events are relatively uncommon in patients receiving etomidate. The medication has few to no hemodynamic effects, and its neutral cardiovascular profile is one of the most appealing aspects of this agent. Adrenocortical suppression has been reported after the use of a single bolus of etomidate, (9) but the significance of this effect is believed to be inconsequential. (10) Muscle twitching generally is well tolerated, and emergence nausea and vomiting have been reported. Respiratory depression and hypoxia are possible. The incidence appears to be 3 to 15 percent. (11-14) Patients have responded well to supplemental oxygen; in rare instances, patients have required bag-valve-mask-assisted ventilation. (11-13) Etomidate has been shown to be safe and effective for PSAA, and is an excellent choice of agent. (11-14)

KETAMINE

Ketamine has gained favor for PSAA in children because of its reliable effects and strong safety profile. Ketamine is a rapidly acting dissociative anesthetic that produces a profound analgesic effect. Onset, duration, and dosage vary according to the route of admin istration. The dose may be repeated and titrated to effect with no cumulative adverse risk profile.

Ketamine is contraindicated in patients who are hypersensitive to the medication, and in those in whom a hypersympathetic state might be deleterious, such as patients with elevated intracranial or intraocular pressure, or those with coronary artery disease. Care must be taken in any patient with upper or lower respiratory tract pathology because of the low risk for airway compromise. Ketamine is a pregnancy category C medication.

Adverse effects of ketamine include recovery agitation, transient airway complications such as laryngospasm, and emesis. (15) Excessive salivation also may occur and can be treated with anticholinergics. (16) Although the use of benzodiazepine adjuncts to ketamine sedation commonly is recommended, it has not been demonstrated to be useful in preventing recovery agitation in children. (17,18) Ketamine is safe for use in adults, but careful patient selection is mandatory. (19) Concomitant use of midazolam should be considered in adults to blunt the potential sympathomimetic effects of ketamine and to reduce the likelihood of emergence reactions. (20) Ketamine should be avoided in patients who are predisposed to psychotic behavior.

Respiratory depression is uncommon with ketamine; however, as with all agents, it can occur, and the physician must be prepared to manage the patient's airway. (15,19) Laryngospasm has an incidence of 0.4 percent in patients receiving ketamine, but it is generally transient, and patients can be ventilated manually via bag-valve mask when necessary. (20) Overall, ketamine has an excellent safety record with use in children and adults.

FENTANYL AND MIDAZOLAM

The combination of fentanyl and midazolam has been used for many years. These medications have a rapid onset and a short duration of action, and are safe and effective for PSAA.

Midazolam is a benzodiazepine that can be delivered by a number of different routes, but intravenous administration provides the fastest onset of action. Midazolam undergoes hepatic metabolism and renal excretion, and prolonged effects may be seen with dysfunction of either organ system. It is a pregnancy category D medication. Midazolam is a sedative, amnestic, and anxiolytic medication with no analgesic properties. For this reason, it is used commonly with an opioid analgesic such as fentanyl. (21)

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid. When given intravenously, the time of onset is one to two minutes and the duration of clinical effect is about 30 to 60 minutes. Fentanyl is metabolized by the liver, but its short duration of effect is attributable to rapid redistribution from the central nervous system. It is a pregnancy category C drug. Because fentanyl is a pure analgesic, it should not be used alone for PSAA. (22)

Fentanyl and midazolam are titrated easily and are widely available. The biggest drawback of this combination is the potential for cardiac and respiratory depression. The medications should be given in slow, incremental doses rather than using bolus administration. Respiratory depression may occur in 25 percent or more of patients. (23,24)

REVERSAL AGENTS

One unique advantage to the combination of fentanyl and midazolam is that both agents have antagonists that can be used to reverse the effects. Naloxone and flumazenil effectively terminate the effects of fentanyl and midazolam, respectively.

Routine use of reversal agents should be avoided. Because the duration of effect of the sedative agents may exceed that of the reversal agents, a reversed patient may appear recovered temporarily then return to a sedated state. Reversal agents should be administered only to prevent a major complication, such as aspiration or cardiorespiratory compromise, and should be followed by a long observation period to ensure recovery. Physicians should be especially careful with flumazenil because its use can be associated with status epilepticus, mainly in patients with unidentified benzodiazepine abuse or seizure disorder.

Commonly used agents for PSAA are listed in Table 2.

Recovery from PSAA

Patients recovering from PSAA should be approached with the same diligence as when they are induced. Once the noxious stimuli from the procedure are removed, the cardiorespiratory depressant effects of the medications may become more dominant. Therefore, all patients should be monitored by trained personnel at the bedside until no risk of cardiorespiratory depression remains. Patients should be recovered to an age-appropriate baseline mental status before being discharged.

The authors indicate that they do not have any conflicts of interest. Sources of funding: none reported.

REFERENCES

(1.) American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy for procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 1998;31:663-77.

(2.) American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Pediatrics 1992;89(6 pt 1):1110-5.

(3.) Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology 1996;84:459-71.

(4.) Innes G, Murphy M, Nijssen-Jordan C, Ducharme J, Drummond A. Procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Canadian consensus guidelines. J Emerg Med 1999;17:145-56.

(5.) Green SM, Krauss B. Procedural sedation terminology: moving beyond "conscious sedation." Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:433-5.

(6.) Australasian College for Emergency Medicine, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists; Faculty of Pain Medicine and Joint Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Statement on clinical principles for procedural sedation. Emerg Med 2003;15:205-6.

(7.) Green SM, Krauss B. Pulmonary aspiration risk during emergency department procedural sedation--an examination of the role of fasting and sedation depth. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9:35-42.

(8.) Etomidate. USP Dispensing Information. Englewood, Colo.: Micromedex 2001;1:1459-61.

(9.) Absalom A, Pledger D, Kong A. Adrenocortical function in critically ill patients 24 h after a single dose of etomidate. Anaesthesia 1999; 54:861-7.

(10.) Schenarts CL, Burton JH, Riker RR. Adrenocortical dysfunction following etomidate induction in emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med 2001;8:1-7.

(11.) Vinson DR, Bradbury DR. Etomidate for procedural sedation in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:592-8.

(12.) Ruth WJ, Burton JH, Bock AJ. Intravenous etomidate for procedural sedation in emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med 2001;8:13-8.

(13.) Burton JH, Bock AJ, Strout TD, Marcolini EG. Etomidate and midazolam for reduction of anterior shoulder dislocation: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2002;40:496-504.

(14.) Dickinson R, Singer AJ, Carrion W. Etomidate for pediatric sedation prior to fracture reduction. Acad Emerg Med 2001;8:74-7.

(15.) Green SM, Rothrock SG, Lynch EL, Ho M, Harris T, Hestdalen R, et al. Intramuscular ketamine for pediatric sedation in the emergency depart-ment: safety profile in 1,022 cases. Ann Emerg Med 1998;31:688-97.

(16.) Flood RG, Krauss B. Procedural sedation and analgesia for children in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2003;21:121-39.

(17.) Sherwin TS, Green SM, Khan A, Chapman DS, Dannenberg B. Does adjunctive midazolam reduce recovery agitation after ketamine sedation for pediatric procedures? A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2000;35:229-38.

(18.) Wathen JE, Roback MG, Mackenzie T, Bothner JP. Does midazolam alter the clinical effects of intravenous ketamine sedation in children? A double-blind, randomized, controlled, emergency department trial. Ann Emerg Med 2000;36:579-88.

(19.) Chudnofsky CR, Weber JE, Stoyanoff PJ, Colone PD, Wilkerson MD, Hallinen DL, et al. A combination of midazolam and ketamine for procedural sedation and analgesia in adult emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med 2000;7:228-35.

(20.) Green SM, Li J. Ketamine in adults: what emergency physicians need to know about patient selection and emergence reactions. Acad Emerg Med 2000;7:278-81.

(21.) Midazolam. USP Dispensing Information. Englewood, Colo.: Micromedex 2001;1:2074-81.

(22.) Fentanyl derivatives. USP Dispensing Information. Englewood, Colo.: Micromedex 2001;1:1495-503.

(23.) Kennedy RM, Porter FL, Miller JP, Jaffe DM. Comparison of fentanyl/midazolam with ketamine/midazolam for pediatric orthopedic emergencies. Pediatrics 1998;102(4 pt 1):956-63.

(24.) Bailey PL, Pace NL, Ashburn MA, Moll JW, East KA, Stanley TH. Frequent hypoxemia and apnea after sedation with midazolam and fentanyl. Anesthesiology 1990;73:826-30.

TODD B. BROWN, M.D., is clinical instructor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He was formerly a community emergency physician at Henry Mayo Newhall Memorial Hospital, Santa Clarita, Calif. Dr. Brown received his medical degree from the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, and completed a residency in emergency medicine at the University of California Los Angeles/Olive View.

LUIS M. LOVATO, M.D., is an assistant clinical professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. He also is the director of emergency critical care in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Olive View/UCLA Medical Center in Sylmar, Calif.

DINORA PARKER, B.S., is research assistant for LA Biomed at Harbor/UCLA Medical Center. She received her Bachelor of Science degree in psychobiology from the UCLA School of Letters and Science, and was a research assistant at UCLA.

Address correspondence to Todd B. Brown, M.D., 1844 Russet Hill Circle, Hoover, AL 35244 (e-mail: bransonbrown@comcast.net). Reprints are not available from the authors.

COPYRIGHT 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group