When one of their classmates recounted a story of being drugged in a bar and then having to go to hospital for treatment, a group of nursing students decided to take action and looked to RNABC's Standards for Registered Nursing Practice in British Columbia for guidance.

I was no ordinary Monday. But then ow could it be, considering the weekend that came before?

Jennifer Abraham, a Vancouver nursing student, was struggling to concentrate on her anatomy lab. No matter how hard she tried, she couldn't quiet the turmoil in her mind. Turning to her classmates and friends, she hesitatingly began to relate the details of what happened to her only two days earlier. Enjoying a night out with two girlfriends at a local bar, Abraham met "Jeff," a well-spoken, good-looking man who told her he was a dentist. After a while the man ordered drinks for her and her two friends. She was the only one of the three friends who consumed her drink. Within 15 minutes, she began to feel peculiar - but it wasn't the alcohol that was making her feel this way.

"I had a really intense muscle spasm that I could not stop. I would describe it as a seizure but I was conscious," Abraham says. "I knew that I'd been drugged."

Unbeknownst to her, the man had slipped a date rape drug into her drink. Her friends got her home safely, but later that night she became seriously ill and was rushed to hospital for treatment. Abraham was lucky.

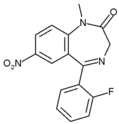

Date rape drugs are substances such as Rohypnol (a trade name for flunitrazepam) and gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB). Tasteless, odourless and colourless, these drugs are sometimes surreptitiously slipped into drinks at bars, clubs, raves and private parties. Sexual predators and other malicious individuals use them to incapacitate a victim, leaving the person confused, unable to resist and sometimes unconscious. Many of these drugs pass out of a person's system within 24 hours and are difficult to detect. When the drug wears off, the person often doesn't remember what happened.

When Abraham's classmates heard her tale, they were horrified, but not shocked. As it turned out, about half of her classmates knew a friend or relative who had been violated in this way. Their revulsion quickly turned to anger and to expressions of frustration that no one was doing anything to prevent this sinister form of assault.

But someone soon did. Three of the nursing students who were in that Langara College classroom (including Abraham) used that traumatic incident as a catalyst for the creation of a tool to promote health, educate the public and provide a health service - all in the public interest. In other words, they began to put RNABC's Standards for Registered Nursing Practice in British Columbia into action.

Putting Standards into Action

In collaboration with the Vancouver Police Department, Abraham, Marissa MacDonald and Thalia Martens created Student Nurses for Clean Drinks (SNCD), an educational project aimed at raising awareness about date rape drugs and the unsavoury people who give them to unsuspecting victims. The ongoing campaign involves visiting downtown Vancouver streets, bars and clubs where nursing students and police officers talk with patrons and hand out informative flyers and cards warning people about the danger of leaving drinks unattended.

In carrying out this campaign, these nursing students are meeting several RNABC Standards for Registered Nursing Practice in British Columbia, such as Standard 2, Indicator 2: Shares nursing knowledge with clients, colleagues, students and others and Standard 5, Indicator 4: Advocates and participates in changes to improve client care and nursing practice.

The idea for SNCD started soon after that day in class. MacDonald, an RNABC student representative, couldn't get Abraham's revelation and her classmates' reaction to it out of her mind.

"I remember coming home and voices were echoing in my head of everybody saying 'It happened to me too' and 'When will this end?' I was so furious," MacDonald recalls. "I was in the shower and I stopped the water, raced downstairs and said 'Mom, we're going to do something to stop this problem.' I really didn't know what."

Not for long, however. During a subsequent brainstorming session, MacDonald, Martens and Abraham drew on their knowledge of leadership, health promotion, client teaching, working with colleagues, and even pharmacology. As an RNABC student representative, MacDonald says she relied on her leadership skills, but more important, she tapped into her knowledge of working with a team of leaders - her colleagues and members of the Vancouver Police Department.

"We had so much learning (in school) about health promotion and about the RNABC Standards and health and well-being. A lot of that fueled what we did." MacDonald says. "We were no longer just young adults faced with a problem. We were nursing students who had this baseline of knowledge of how we could promote these health issues."

Says Abraham, "What was amazing is that instead of just getting mad that this was happening and mad that the police couldn't catch the guy, we decided to do something really pro-active about it."

Focus on Prevention

Martens points out that the project they came up with fits perfectly with what they were learning in class, "It's been drilled over and over again to us in class that we should focus on prevention. We want to change behaviour . . . And this falls right into that category - teaching people and, through education, potentially preventing this really nasty situation from developing."

Once they hatched their idea, the hard work began. The three approached the Vancouver Police Department and received immediate encouragement and support. With two members of the police on board - Constable Stephen Thacker and Constable Christian Lowe - the team went through months of research, writing, design and sending materials back and forth. Exactly how the flyers and cards would look and what they would say had to be worked out.

The nursing students wanted to come up with a slogan that would express what was happening in positive and relevant terms. They had to keep in mind that their clients were mostly people in their twenties and thirties. They decided to use the word "tipping" to describe the act of putting unwanted drugs in drinks. Their motto became "Don't get tipped!"

The cards they created are bright, eye-catching and have short, snappy messages. One for instance, with a picture of an intriguing, dark-haired man, states, "Last night you met Jeff. The first thing you noticed was the sparkle in his eyes. Then his sexy smile. And then his great ass. It's too bad no one noticed his hands as he tipped your drink."

On the back of the cards are five guidelines to avoid getting tipped and signs and symptoms of date rape drug ingestion.

The three nursing students soon realized that they were not prepared to counsel clients who had already been tipped. They contacted the BC NurseLine and were given NurseLine magnets to distribute as a support resource. The three also designed a website (www.studentnurses.4t.com), wrote a newsletter and put together a package for volunteers. Along the way, they received financial help from the Langara Students' Union and a Vancouver company called TR Trades.

Hitting the Street

On Oct. 8, 2004, the team, which included 11 volunteers, hit the Granville Street entertainment district, a popular bar and club strip in downtown Vancouver. They went out again Dec. 4, 2004. The response was overwhelming. Bar owners were welcoming. Strangers opened up and shared experiences. They also received news coverage from television, radio and newspapers.

"It was fabulous being out there in clubs and bars," says Abraham. "We received lots of positive comments."

But they weren't the only ones doing the educating. Talking and meeting people who were affected by tipping was a learning experience in itself. Martens says they quickly learned that not all victims of date rape drugs are female.

Constable Stephen Thacker says that while the majority of victims are females, "this can happen with every type of relationship. There's always been something in our society to lessen inhibitions. It used to be alcohol. Now it's gone into the chemical realm."

Because perpetrators are so hard to catch (they must be witnessed in the act) and because these drugs are hard to identify and often cause memory loss, Thacker calls tipping "almost the perfect crime." Yet, he emphasizes, it's probably one of the easiest crimes to prevent.

"Anytime you can educate the public, it's good," Thacker says. "In the short term, you may not know what sort of positive influence you'll have, but long term, any form of education has positive effects."

And that's where SNCD comes in. The project is far from over and indeed has big plans. There will be more nights on the street and in clubs and bars. In addition, with consent from the Langara College nursing faculty, the three hope to incorporate SNCD into their community nursing component next fall. Martens says the faculty has been "so supportive of us."

"We're hoping to go into high schools similar to what the MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Driving) people do," she says. "If we can get our whole class involved, we could potentially reach thousands of kids in the Lower Mainland. And that would be absolutely awesome."

Abraham, MacDonald and Martens will receive their degrees from the University of Victoria in 2007. Can they realistically, keep SNCD going till then? Says MacDonald, "Once people no longer need to be reminded to watch their drinks, we'll retire with satisfaction."

ALICIA PRIEST IS A VICTORIA-BASED FREELANCE WRITER.

Copyright Registered Nurses Association of British Columbia Apr 2005

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved