Fluoxetine and Side Effects in the Geriatric Population

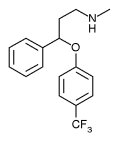

TO THE EDITOR: Drs. Gurvich and Cunningham state in their article(1) on psychotropic drugs in nursing homes that fluoxetine (Prozac) is not recommended in the geriatric population because of its longer half-life of active metabolite relative to other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), resulting in the potential for a longer duration of side effects.

While it is true that fluoxetine's active metabolite has a half-life of up to 16 days, because of its low incidence of side effects compared with other SSRIs, it has a very low discontinuation rate compared with paroxetine (Paxil), fluvoxamine (Luvox) and sertraline (Zoloft).(2) Furthermore, because fluoxetine has a longer half-life, a missed dose is not as significant as it is with other SSRIs, and fluoxetine is not associated with the discontinuation syndrome that is found with other SSRIs.(3) Fluoxetine should not be avoided in the geriatric population and may even be the drug of choice for selected patients.

REFERENCES

(1.) Gurvich T, Cunningham JA. Appropriate use of psychotropic drugs in nursing homes. Am Fam Physician 2000;61:1437-46.

(2.) Price JS, Waller PC, Wood SM, MacKay AV. A comparison of the post-marketing safety of four selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors including the investigation of symptoms occurring on withdrawal. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1996;42:757-63.

(3.) Coupland NJ, Bell CJ, Potokar JP. Serotonin reuptake inhibitor withdrawal. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16:356-62.

IN REPLY: We agree that selected geriatric patients respond well to fluoxetine. In fact, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved labeling for fluoxetine to be used to treat patients with depression in the geriatric population.

A placebo-controlled study(1) that contributed to this recent FDA approval evaluated 671 geriatric patients with major depression. The study concluded that 20 mg per day of fluoxetine is more effective than placebo and is as equally well tolerated as placebo. However, the patients participating in the study were outpatients, an average age of 67 years and were considerably younger and healthier than patients in a typical skilled nursing facility.

Our article(2) focused on the more frail elderly patient who often responds differently to medications. Dosing titration of fluoxetine must be done carefully in this population: "The long half-lives of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine promote insidious drug accumulation, which takes considerable time to correct."(3) One way to use the long half-life to advantage, however, would be to dose fluoxetine every other day, thus reducing the risk of side effects and accumulation without compromising drug effectiveness.

Another issue to consider is drug interactions. Patients in skilled nursing facilities are often given multiple medications, and causing new drug interactions is a constant concern. Fluoxetine and its metabolite are more potent P450 inhibitors than sertraline, and citalopram (Celexa) appears to inhibit the P450 minimally, if at all.(3,4) Clearly, drug selection is dependent on the practitioner's clinical experience and individual patient's tolerance of a given medication.

REFERENCES

(1.) Tollefson GD, Holman SL. Analysis of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale factors from a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in geriatric major depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1993;8:253-9.

(2.) Gurvich T, Cunningham JA. Appropriate use of psychotropic drugs in nursing homes. Am Fam Physician 2000;61:1437-46.

(3.) Hay DP, Rodriguez MM, Franson KL. Treatment of depression in late life. Clin Geriatr Med 1998; 14:33-46.

(4.) Drug facts and comparisons. St. Louis, Mo.: Facts and Comparisons, 1999:918-26.

Treatment of Depression in the Elderly

TO THE EDITOR: I am responding to the recently published review by Drs. Gurvich and Cunningham,(1) "Appropriate Use of Psychotropic Drugs in Nursing Homes." I believe that the data presented regarding the clinical efficacy and side effect profile of the newer antidepressant mirtazapine (Remeron) may be potentially misleading.

The number of safe and effective medications with approved labeling for the treatment of depression has increased significantly during the past 10 years. The brief mention of mirtazapine in the review by Gurvich and Cunningham(1) is understandable in light of the number of new agents they needed to discuss. However, their discussion of this extensively used noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA) appears to suggest a more troublesome toxicity profile that conflicts with what I have seen in clinical trials and in practice.

The authors state that research on the use of this drug in the geriatric population has been limited. However, many randomized, double-blind, controlled trials and clinical reports support the use of mirtazapine as a first-line agent for the treatment of depression in these and other patient types; these studies include two that were specifically directed at the elderly population.(2-4) Tolerability of mirtazapine was examined in elderly persons by Montgomery,(5) who found no difference in tolerance between patients older than 65 years and younger patients taking mirtazapine.

Drs. Gurvich and Cunningham(1) raised concerns that mirtazapine might cause anticholinergic effects caused by weak muscarinic blockade; however, a retrospective database review of safety by Montgomery(5) revealed that mirtazapine has virtually no adverse anticholinergic effects (editor's note: data published in a journal supplement sponsored by the manufacturer of mirtazapine). The authors also state that mirtazapine can cause orthostatic hypotension caused by weak alpha-adrenergic blockade. However, in clinical trials, orthostatic hypotension occurred less in mirtazapine-treated patients than in placebo-treated patients.(6)

In conclusion, from my review of the literature and from my clinical experience: (1) mirtazapine is effective in the treatment of depression; (2) side effects of mirtazapine, such as somnolence and increased appetite, can be beneficial in the depressed elderly patient who is not sleeping or eating, especially in the long-term care setting and (3) orthostatic hypotension has not been demonstrated to be more clinically significant with mirtazapine than with other new antidepressants.

REFERENCES

(1.) Gurvich T, Cunningham JA. Appropriate use of psychotropic drugs in nursing homes. Am Fam Physician 2000;61:1437-46.

(2.) Halikas JA. Org 3770 (mirtazapine) versus trazadone: a placebo controlled trial in depressed elderly patients. Hum Psychopharmacol 1995;10:S125-33.

(3.) Hyberg OJ. A double-blind multicentre comparison of mirtazapine and amitriptyline in elderly depressed patients. Drugs 1999;57:607-31.

(4.) Holm K, Markham A. Mirtazapine: a review of its use in major depression. Drugs 1999;57:607-31.

(5.) Montgomery SA. Safety of mirtazapine: a review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995;10(suppl 4):37-45.

(6.) Physician's Desk Reference 2000. Montvale, N.J.: Medical Economics Company: 2109-11.

Dr. Mofsen receives honoraria and grant/research support from Organon, Inc., (manufacturer of mirtazapine), Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation, Abbott Laboratories and Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Inc. He is a consultant for Eli Lilly, Novartis, Janssen Pharmaceutical Company and Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, and affiliated with the Speakers Bureau for Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Janssen Pharmaceutical Company.

IN REPLY: Selecting an appropriate antidepressant for any given patient is a complicated process and is dependent on the prescriber's clinical experience and the patient's ability to tolerate the drug. Mirtazapine is clearly better tolerated than tricyclic agents and is appropriate for some geriatric patients. Mirtazapine may be especially helpful in those who need a sedating agent or in patients who need to gain weight. An increase in appetite was reported in 17 percent of patients taking mirtazapine.(1) Some dizziness and anticholinergic side effects, however, were reported in clinical trials. We believe that prescribers need to be aware of the possibility of these side effects so that they can factor them into their clinical decision making.

REFERENCE

(1.) Drug facts and comparisons. St. Louis, Mo.: Facts and Comparisons, 2000:900-3.

COPYRIGHT 2001 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group