Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a rare, adverse reaction to neuroleptic medications. Although incidence of NMS in the geriatric population has never been studied rigorously, more than 200 cases of NMS in older patients have been reported in the medical literature.

Three issues make NMS a valid concern for clinicians treating older adults:

* On a theoretical basis, older patients may be more susceptible to NMS since dopamine activity decreases with age.

* Some studies identify dementia and cerebral vascular accidents, two common conditions in the geriatric population, as risk factors for NMS.

* Clinicians are increasingly using neuroleptics to treat agitation in older adults with dementia and delirium.

Case study

Mr. M is a 66-year-old retired engineering consultant and math professor with a history of cerebrovascular accidents and vascular dementia. After he experienced worsening paranoid delusions, his spouse brought him to the hospital and he was subsequently admitted to the geriatrics ward.

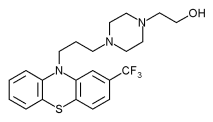

During the 4 months prior to admission, the patient had been taking low doses of risperidone (0.25 to 1.0 mg/d) for paranoia. A rapid titration of risperidone to 2 mg/tid led to orthostatic hypotension. On admission, risperidone was discontinued for several days, then restarted at a lower dose (1 mg/qam and 2 mg/qhs).

Two weeks after restarting the risperidone, the patient became febrile (38[degrees]C), and a complete blood count revealed an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count of 12.2x[10.sup.9]/L. Warm, erythematous interscapulum skin suggested cellulitis, and antibiotic treatment was initiated. Further examination ruled out cellulitis, but a urine culture was found to be positive and antibiotic treatment was continued.

Initially, the antibiotic therapy appeared to be effective as the patient's temperature and WBC count normalized. However, over the course of a week, the patient's temperature fluctuated between 37[degrees]C and 38.7[degrees]C, and his WBC count rose again to 15.1x[10.sup.9]/L. He was tachycardic and his level of consciousness fluctuated. During this week, a warm, swollen left knee was aspirated to rule out septic arthritis. The results were positive for crystals; there was no growth on culture. Infectious disease and neurology consultants deemed the likelihood of a CNS infection as low.

On the fifth day of antibiotic treatment, the patient continued to be febrile (38.4[degrees]C) and to have an elevated WBC count of 15.1x[10.sup.9]/L. At this time cogwheel rigidity was noted on physical examination. Due to the lack of response to antibiotic therapy and increased limb rigidity, a diagnosis of NMS was made. Risperidone therapy was immediately discontinued. At time of discontinuation, serum levels of creatine kinase (CK) were normal (range 24 to 195 U/L), but two days after withdrawal of risperidone, CK levels rose to 738 U/L. The patient's urine was negative for myoglobin and renal function remained stable. With intravenous hydration and supportive nursing care, all of the patient's symptoms resolved over the course of 2 weeks and his laboratory values returned to normal.

Epidemiology

NMS is a rare, adverse reaction (0.2% in all patients) (1) to psychoactive medications, usually neuroleptics. Since the 1960's, reports have described cases of NMS related to all neuroleptic medications, including the atypicals (olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, and clozapine). Cases of NMS have also been described in patients taking non-neuroleptic medications, such as tricyclic antidepressants, (2) and following withdrawal of antiparkinsonian medications. (3)

Antipsychotic medications, especially the atypicals, are being increasingly used for treatment of agitation in patients with dementia and delirium. With the growing number of older patients and the increased use of neuroleptics in this population, clinicians must be alert to a likely increase in the number of cases of NMS.

Pathogenesis

The proposed mechanism of NMS is a widespread block of dopaminergic activity in the brain. (4) This theory explains why both administration of dopamine antagonists (neuroleptics) and abrupt withdrawal of dopamine agonists (antiparkinsonian drugs) could result in an NMS-like clinical picture. Older patients may be more susceptible to NMS since many studies have concluded that dopamine activity decreases with age. (5,6)

Research published subsequent to this case suggests that NMS may be related to malignant catatonia and not malignant hyperthermia (dopamine imbalance). In this regard, the researchers have suggested that electroconvulsive therapy and benzodiazepines, commonly used for the treatment of catatonia, have been effective in the treatment of NMS. (7)

Risk factors

Over the past two decades, researchers have proposed several risk factors for the development of NMS. Unfortunately, these risk factors vary from study to study, and no single risk factor has been consistently recognized.

Most proposed risk factors have come from epidemiological studies in which the cases were not matched to controlled subjects. However, in one case-control study of young adults (average age 37), Keck et al identified the following as statistically significant risk factors:

* psychomotor agitation;

* maximum, mean, and total dose of neuroleptic administered;

* number of intramuscular injections; and

* rate of dose increase. (8)

In another case-control study of young adults (average age 29.7), Chopra et al found three significant risk factors:

* a history of concomitant physical or neurological illness,

* use of depot fluphenazine decanoate, and

* higher mean doses of neuroleptic. (9)

In both studies, cases and controls were matched for age, so this factor was not studied.

Rosenbush and colleagues cited an increased risk for NMS in patients with concomitant brain pathology (history of cerebral vascular accidents, seizure disorders, chronic "organic brain syndromes"). (10) Shalev and Munitz found preexisting "organic brain disease" correlated to a higher risk of mortality. (11) Thus, dementia and cerebral vascular accidents, two common conditions in the older adult, may increase the risk of NMS in this patient population.

Diagnosis

A general consensus for the diagnostic criteria for NMS does not currently exist. One of the least stringent sets of criteria comes from the DSM-IV-TR, (12) whereas Adityanjee (13) has proposed the most stringent set of criteria for NMS (table 1). In general, most sets of criteria include hyperpyrexia and muscular rigidity, along with one or more of the less important findings (eg, autonomic instability, altered sensorium, increased serum CK levels, and myoglobinuria).

Many cases published in the literature have been labeled as NMS despite the absence of classical presenting signs. Schneiderhan and Marken published a case report of NMS in the absence of hyperpyrexia. (14) Wong published a case report of two patients with supposed NMS, both of whom failed to develop muscle rigidity. (15) These and other reports of so-called atypical NMS lend credence to the idea proposed by many authors that NMS represents a spectrum of pathological processes. Debate on the validity of this concept continues.

Given its variable presentation, NMS should be included in the differential diagnosis for any patient on neuroleptics who presents with fever. Before a diagnosis of NMS is made, all other possible causes of elevated temperature must be ruled out, and the fever should coincide with other clinical features of NMS such as muscle rigidity, altered mental status, and autonomic lability.

The differential diagnosis of NMS is very broad (table 2). Most importantly, an infectious source of fever must be ruled out. A lumbar puncture should be considered to differentiate NMS from viral encephalitis or postinfectious encephalomyelitis. Table 3 details clinical features of NMS.

NMS must also be distinguished from syndromes caused by other pharmacologic agents (such as serotonin syndrome and malignant hyperthermia). (16-19) (Table 4, located at www.geri.com, compares clinical features of NMS, serotonin syndrome, and malignant hyperthermia.)

Complications

The major complications of NMS are respiratory disturbance and renal failure. Renal failure is associated with the occurrence of disseminated intravascular coagulation and rhabdomyolysis. (20) Estimates of mortality following NMS range from 4% to 22%, (21) with myoglobinemia and renal failure being strong predictors of death.

Treatment

The cornerstones of treatment in any suspected case of NMS are the immediate withdrawal the offending neuroleptic and the provision of supportive therapy (ie, hydration and supportive nursing care), to prevent the major complications of NMS. Various pharmacologic agents have been used to treat NMS--primarily dantrolene, bromocriptine, and amantadine; benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy have also been suggested. Some researchers have suggested that electroconvulsive therapy and benzodiazepines may be effective in the treatment of NMS. (22) However, debate continues as to the effectiveness of such pharmacotherapy versus supportive therapy alone, especially as these drugs are often poorly tolerated (eg, may trigger delirium) in geriatric patients. Supportive therapy is suggested pending evidence of benefit of such pharmacotherapy in these patients.

Conclusion

NMS is a rare, adverse reaction to psychoactive medications that is usually reversible once the offending treatment is discontinued; however, its presence poses a significant risk of mortality to geriatric patients. With the increasing use of neuroleptics in the geriatric population, clinicians must be aware of NMS and its warning signs.

References

(1.) Caroff SN, Mann SC. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Med Clin North Am 1993; 77(1):185-202.

(2.) Heyland D, Sauve M. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome without the use of neuroleptics. CMAJ 1991; 145(7): 817-9.

(3.) Toru M, Matsuda O, Makiguchi K. Sugano K. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome-like state following withdrawal of antiparkinsonian drugs. J Nerv Ment Dis 1981; 169(5):324-7.

(4.) Weller M, Kornhuber J. A rationale for NMDA receptor antagonist therapy of the neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Med Hypotheses 1992; 38(4):329-33.

(5.) Allard P, Marcusson JO. Age-correlated loss of dopamine uptake sites labeled with [3H]GBR-12935 in human putamen. Neurobiol Aging 1989; 10(6):661-4.

(6.) Antonini A, Leenders KL, Reist H, Thomann R, Beer HF, Locher J. Effect of age on D2 dopamine receptors in normal human brain measured by positron emission tomography and 11C-raclopride. Arch Neurol 1993; 50(5):474-80.

(7.) Caroff SN. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: still a risk, but which patients may be in danger? Curr Psychiatry Online [serial online] December 2003; 2(12).

(8.) Keck PE, Pope HG, Cohen BM, McElroy SL, Nierenberg, AA. Risk factors for neuroleptic malignant syndrome. A case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:914-8.

(9.) Chopra MP, Prakash SS, Raguram R. The neuroleptic malignant syndrome: an Indian experience. Compr Psychiatry 1999; 40(1):19-23.

(10.) Rosebush P, Stewart T. A prospective analysis of 24 episodes of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146(6):717-25.

(11.) Shalev A, Munitz H. The neuroleptic malignant syndrome: agent and host interaction. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1986; 73(4):337-47.

(12.) American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC. 2000; 795-8.

(13.) Adityanjee, Singh S, Singh G, Ong S. Spectrum concept of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 153:107-11.

(14.) Schneiderhan ME, Marken PA. An atypical course of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. J Clin Pharmacol 1994; 34(4):325-34.

(15.) Wong MM. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: two cases without muscle rigidity. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1996; 30(3):415-8.

(16.) Bertorini TE. Myoglobinuria, malignant hyperthermia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and serotonin syndrome. Neuro Clin 1997; 15(3):649-71.

(17.) Birmes P, Coppin D, Schmitt L, Lauque D. Serotonin syndrome: a brief review. CMAJ 2003; 168(11):1439-42.

(18.) Carbone JR. The Neuropelptic malignant and serotonin syndromes. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2000; 18 (2):317-25.

(19.) Gurrera RJ. Is neuroleptic malignant syndrome a neurogenic form of malignant hyperthermia? Clin Neuropharmacol 2002; 25(4):183-93.

(20.) Taniguchi N, et al. Classification system of complications in neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 1997; 19(3):193-9.

(21.) Shalev A, Hermesh H, Munitz H. Mortality from neuroleptic malignant syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry 1989; 50(1):18-25.

Dr. Nicholson is a post-doctoral fellow in medical informatics at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon.

Dr. Chiu is assistant professor/ physician in the division of geriatric medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Disclosure: The authors have no real or apparent conflicts of interest related to the subject under discussion.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Advanstar Communications, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group