TO THE EDITOR: Pneumoperitoneum usually indicates a surgical emergency because of visceral perforation in 85 to 95 percent of cases. Some cases of pneumoperitoneum can and should be managed conservatively. We present a case report of a patient with benign asymptomatic pneumoperitoneum and review the causes of this uncommon entity.

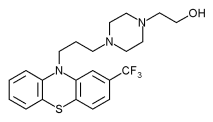

An 82-year-old woman with a history of schizophrenia and hypothyroidism presented to a local hospital with a one-week history of 20-minute episodes of dizziness associated with a frontal headache that worsened on standing. She denied any other symptoms. Chronic daily medications were fluphenazine, benztropine, levothyroxine, and aspirin. Evaluation included a normal physical examination, complete blood count, chemistry panel, electrocardiogram, and computed tomography (CT) scan of the head. Chest radiography initially was read as normal. At follow-up two weeks later, the patient's complaints were unchanged, and an examination was again normal except for mild abdominal distension. Radiology reports from the hospital revealed bilateral pneumoperitoneum below the diaphragms noted on the chest film. Repeat films were unchanged, and an abdominal CT scan taken the next day was read as "significant free intra-abdominal air throughout the abdomen" with "pneumatosis in multiple small bowel loops" (see accompanying figure). At follow-up visits up to five months later, the patient felt well without gastrointestinal complaints or changes in abdominal examination, and her headache and dizziness had resolved.

[FIGURE OMITTED]

Five categories of benign nonsurgical pneumoperitoneum have been described and are discussed here.

Pseudopneumoperitoneum involves the simulated appearance of free air on radiographic examination. This is differentiated from true pneumoperitoneum in that the air does not shift with change in position of the patient. The most common causes of benign nonsurgical pneumoperitoneum are abdominal, with perioperative and endoscopic procedures being the most frequent causes in this category. Open and laparoscopic abdominal surgeries often are followed by pneumoperitoneum visible for up to six days on abdominal CT scan. Our patient had pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (PCI), a less common abdominal cause of pneumoperitoneum. Multiple submucosal and subserosal air-filled cysts form throughout the gastrointestinal tract. The terminal ileum is the most common location, but the cysts can be found in other sites including the omentum and mesentery. (1) PCI is most commonly idiopathic but also can be associated with connective tissue diseases. Rarely, PCI is associated with chemotherapy, inflammatory bowel disease, small bowel resection, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, gastric outlet obstruction, jejunoileal bypass, diverticular disease, nontropical sprue, sclerotherapy, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, organ transplant, (2) or chronic lung disease. (3)

Thoracic causes of pneumoperitoneum include mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and pneumothorax or tracheal rupture. Rare gynecologic causes include pelvic manipulation or insufflation, which can be fatal in pregnancy because of air embolization. Miscellaneous causes include cocaine use, diving with decompression, and dental extraction.

Patients with benign pneumoperitoneum often have mild abdominal distension or liver dullness to percussion but generally do not have abdominal tenderness. (3) Patients without history or examination consistent with visceral perforation have been treated successfully with conservative measures such as observation and intravenous fluids. (4) Pneumoperitoneum in the presence of PCI can recur as more cysts rupture and should be managed nonsurgically.

LAURA E. MYRE, M.D.

SUSAN PINON, M.D.

WALTER B. FORMAN, M.D., C.M.D.

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

2211 Lomas Blvd.

Albuquerque, NM 87131

REFERENCES

(1.) Mularski RA, Sippel JM, Osborne ML. Pneumoperitoneum: a review of nonsurgical causes. Crit Care Med 2000;28:2638-44.

(2.) Mezghebe HM, Leffall LD Jr, Siram SM, Syphax B. Asymptomatic pneumoperitoneum diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. Am Surg 1994;60:691-4.

(3.) Maltz C. Benign pneumoperitoneum and pneumatosis intestinalis. Am J Emerg Med 2001;19: 242-3.

(4.) Hussain A, Cox JG. Benign spontaneous pneumoperitoneum in an elderly patient treated medically with recovery. Postgrad Med J 1995;71:252.

Send letters to Jay Siwek, M.D., Editor, American Family Physician, 11400 Tomahawk Creek Pkwy., Leawood, KS 66211-2672; fax: 913-906-6080; e-mail: afplet@ aafp.org. Please include your complete address, telephone number, and fax number. Letters should be submitted on disk, double-spaced, fewer than 500 words, and limited to one table or figure and six references. Please submit a word count. Letters submitted for publication in AFP must not be submitted to any other publication. Possible conflicts of interest must be disclosed at time of submission. Submission of a letter will be construed as granting the AAFP permission to publish the letter in any of its publications in any form. The editors may edit letters to meet style and space requirements.

COPYRIGHT 2004 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group