Lifetime maintenance treatment is recommended for patients with bipolar disorder, somewhat akin to managing chronic medical illnesses such as diabetes or hypertension. Because maintenance therapy must be both safe and effective, ideal medications for bipolar disorder should have three characteristics:

* long-term tolerability

* patient-friendly administration and monitoring

* minimal risk of drug-drug interactions.

This article reviews the tolerability of mood stabilizers used in maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder and offers helpful strategies to maximize their safety.

Tolerability

When treating bipolar disorder, psychiatrists often use divalproex or lithium as foundational therapy because of these agents' beneficial effects, which include control of manic symptoms and predictable response based on serum levels. At the same time, however, divalproex and lithium have potentially serious side effects:

* Divalproex has black-box warnings of hepatotoxicity; pancreatitis, and teratogenicity(1)--its use essentially is contraindicated in pregnant women.

* Long term lithium use has been associated with hypothyroidism, possible renal impairment, and cardiac abnormalities on ECG. (1) It also may have teratogenic potential involving the fetal cardiovascular system, although the risk appears much less than with divalproex. (2)

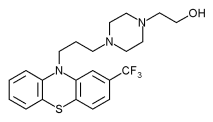

Antipsychotics also are used in treating bipolar disorder, especially to control manic and psychotic symptoms, to augment lithium or divalproex, and when lithium and divalproex are contraindicated, as in pregnancy; Common side effects of typical antipsychotics include parkinsonism, extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), hyperprolactinemia, and tardive dyskinesia (TD). (3) Atypical antipsychotics are less likely to cause EPS, and most do not cause sustained prolactin elevation. (3)

Tardive dyskinesia Atypical antipsychotics also are associated with a lower risk of TD than typical antipsychotics. TD risk varies among the atypicals; clozapine does not appear to increase TD risk, risperidone (4) and quetiapine show low risk in shun-term studies, (5) and the risk with ziprasidone has not been assessed. No case of TD has been reported in randomized, controlled trials using olanzapine in patients with bipolar disorder.

A recent controlled trial (6) suggests a palliative effect of olanzapine in patients with TD, similar to that seen in open trials using clozapine. (7) When 92 patients with a 5-year history of moderate to severe TD received olanzapine, 5 to 20 mg/d, 70% no longer met diagnostic criteria for TD after 8 months. No significant TD worsening was noted when dosages were reduced by 75% at weeks 14 and 24.

Hyperprolactinemia. Chronic hyperprolactinemia is associated with reduced bone mineral density, menstrual irregularities such as amenorrhea, galactorrhea, and sexual dysfunction, particularly in men. (8) Typical antipsychotics elevate serum prolactin levels two to three times greater than normal. (9) Among the atypical antipsychotics, clozapine and quetiapine do not appear to elevate serum prolactin; olanzapine and ziprasidone produce transient prolactin elevation; and risperidone can cause sustained prolactin elevation. (10)

Hyperglycemia and diabetes

Hyperglycemia. Newcomer et al (11) compared serum glucose levels in 48 patients taking antipsychotics for schizophrenia with those of 31 untreated healthy controls. In this study, which was limited by a small sample size, they found that patients treated with olanzapine, clozapine, or risperidone had elevated fasting and post-load serum glucose levels, compared with healthy controls.

Patients taking risperidone in this study had serum glucose levels similar to those seen in patients receiving typical antipsychotics anti less than those of patients receiving olanzapine or clozapine. A follow-up trial using the euglycemic clamp to assess peripheral glucose use found no statistically significant differences among patients receiving typical antipsychotics, risperidone, or olanzapine. (12) Based on these results, the effects of the various antipsychotics on insulin secretion and peripheral glucose utilization do not appear to differ significantly.

In a placebo-controlled study in normal subjects using the hyperglycemic clamp, Sowell et al found no evidence that risperidone or olanzapine directly impaired insulin secretion. They did find that insulin response to hyperglycemia increased and insulin sensitivity decreased--which were thought to be indirect effects related to increased body mass index in study subjects taking either antipsychotic. (13)

These studies do not indicate that any of the atypical antipsychotics directly cause diabetes, but it may be that associated weight gain is an indirect risk factor for glycemic dysregulation.

Diabetes. In patients with bipolar disorder, the relative risk of diabetes has been reported to be two to three times higher than that of the general population. (14)

Koller et al identified cases of new-onset diabetes associated with clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine in a review of the FDA's MedWatch data. (15-17) They suggested atypical antipsychotics may unmask or precipitate diabetes in susceptible patients. Although more new-onset diabetes cases were associated with clozapine and olanzapine than with risperidone, these authors cautioned against drawing conclusions in the absence of direct prospective studies.

A large unpublished epidemiologic study by Cavazonni et al suggested that diabetes may be more common in patients receiving antipsychotics than in the general U.S. population (Figure 1). Diabetes incidence was similar among the antipsychotics that were studied. (18)

In a community-based study, I and colleagues at two hospitals in central New York assessed the prevalence of diabetes and cardiovascular disease in 208 patients, mean age 46 (SD 14.5), with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. (19) We found that 17% had diabetes, 29% had hypertension, and 44% had hypertriglyceridemia. Comparative rates in the U.S. population are 7% for diabetes, 20% for hypertension, (20) and 10% for hypertriglyceridemia. (21) We found no statistical differences in prevalence of diabetes or lipid disorders in patients taking risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, clozapine, or typical antipsychotics.

Summary. At a prevalence of 7%, diabetes is considered an epidemic in the U.S. population. (22,23) It is important to screen all at-risk individuals, including those with chronic diseases or taking antipsychotics. Early treatment can improve glycemic control and decrease the risk of end-organ damage.

Weight gain

Weight gain has been associated with the use of antipsychotics, including the atypicals. (24) Some studies suggest that weight gain predicts therapeutic response, especially to clozapine and olanzapine. (25,26)

Dopamine modulates motivation and reward circuits, so it may be that dopamine deficiency in obese individuals perpetuates pathologic eating. Antipsychotics block dopamine receptors and may result in dopamine dysregulation, leading to weight gain. (27)

Genetic Factors also may be associated with antipsychotic-induced weight gain. In patients with first-episode schizophrenia treated with a controlled diet plus chlorpromazine, risperidone, clozapine, sulpiride, or fluphenazine, those without a variant allele were statistically more likely to gain > 7% of total body weight (P = 0.002 ). (28)

These studies and others suggest that the mechanism of obesity is complex, with antipsychotic use contributing to a number of metabolic and genetic influences.

Controlling weight gain

In a sample of 573 subjects, Kinon et al found that weight gain with olanzapine occurred primarily in the first 38 weeks of treatment, then appeared to plateau. This suggests that early interventions could help limit weight gain. Weight gain associated with divalproex use did not plateau but appeared to trend upward. (29)

Behavioral interventions. Simple behavioral interventions and weight-control algorithms can reduce weight gain and produce weight loss in obese patients taking antipsychotics. All interventions, however, do not work for all patients.

In a study by Nguyen et al, (30) 6 of 22 patients lost weight and 16 others gained a mean [less than or equal to] 5.27 lbs using simple interventions for 12 weeks. The researchers:

* asked patients about increased appetite

* emphasized snacking on fruit and low-fat crackers

* encouraged eating smaller portions

* recommended against "fast food" and greasy foods

* and encouraged exercise, especially walking.

The stepped behavioral approach suggested by Wirshing et al (Figure 2) led to weight loss in patients taking olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol but not clozapine. (31)

[FIGURE 2 OMITTED]

Medical interventions. A number of medications have been studied to control weight gain in patients taking antipsychotics. Because these agents are not indicated for weight management, it is important to discuss them with patients and to document your discussion in their charts.

Twelve patients taking amantadine, mean 175 mg/d, with olanzapine, mean 8.3 mg/d, for 3 to 6 months gained less weight (3.5 kg) than those receiving olanzapine alone (7.2 kg). (32)

In a blinded 16-week study, 132 patients received the histamine [H.sub.2] blocker nizatidine, 150 or 300 mg bid, as adjunctive therapy with olanzapine. Those receiving 300 mg bid gained less weight (2.76 lbs) than those receiving 150 mg bid (4.33 lbs) or placebo (5.53 lbs). (33)

The anticonvulsant topiramate has been associated with weight loss in some patients. (34) Titration should be slow, in increments of 25 mg per week, to a range of 200 to 400 mg qhs. Reported side effects include nephrolithiasis, increased intraocular pressure, and cognitive difficulties. Topiramate use may reduce the efficacy of oral contraceptives.

Orlistat is a lipase inhibitor that is given with a reduced-calorie diet for managing obesity. Taken orally after meals, orlistat use results in <2% systemic fat absorption. Unabsorbed fat is excreted in the feces. It is important to inform patients that this medication is commonly associated with GI side effects, including fecal incontinence.

Hyperlipidemia

Although no direct causal relationship has been established, a recent retrospective study using odds ratios (35) suggested that olanzapine use may be associated with nearly a five-fold increase in risk of developing hyperlipidemia compared with persons unexposed to antipsychotics and a three-fold increase compared with persons taking typical antipsychotics. Retrospective studies have limitations, and prospective controlled data are lacking in this area.

It is important to monitor weight gain and vital signs during psychiatric outpatient visits. In patients with bipolar disorder, screen for diabetes risk with a tasting serum glucose test and for hyperlipidemia with a fasting serum lipid profile before starting antipsychotic therapy and every 3 to 6 months.

In choosing medications, consider evidence of short-and long-term efficacy and ease of use. It is important to educate patients about the safe use of antipsychotics and to aggressively manage side effects. Antipsychotic-associated weight gain, for example, has been significantly reduced with early interventions focusing on nutrition and lifestyle. (36)

References

(1.) American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(suppl):4-50.

(2.) Cohen LS, Rosenbaum JP. Psychotropic drug use during pregnancy: weighing the risks. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59(suppl 2): 18-28.

(3.) Jibson MD, Tandon R. New atypical antipsychotic medications. J Psychiatr Res 1998:32:215-8.

(4.) Brecher M. Long-term incidence of tardive dyskinesia with risperidone (paper presentation). Melbourne, Australia: XXth World Congress of the Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum. 1996.

(5.) Glazer WM. Tardive dyskinesia in quetiapine trial (paper presentation). Acapulco, Mexico: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 1999.

(6.) Kinon BJ. Stauffer VL, Wang L, et al. Olanzapine improves tardive dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia-results of a controlled prospective study (paper presentation), Orlando: American Psychiatric Association's 53rd Institute of Psychiatric Services, 2001.

(7.) Lieberman JA, Saltz BL, Johns CA, Pollack S, Bornstein M. Kane J. The effects of clozapine on tardive dyskinesia. Br J Psychiatry 1991;158:503-10.

(8.) Schlechte JA. Clinical impact of hyperprolactinemia, Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995;9:359 66.

(9.) Clemens JA, Smalstig EB, Sawyer BD. Antipsychotic drugs stimulate prolactin release Psychopharmacol 1974;40:123-7.

(10.) Jansen AL, Zylicz Z, Visscher HW, Jonkman JH. Pharmacokinetics of the novel antipsychotic agent risperidone and prolactin response in healthy subjects, Clin Pharmacol Ther 1993;54(3)257-67.

(11.) Newcomer JW, Haupt DW, Fucetola R, et al. Abnormalities in glucose regulation during antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:337-45.

(12.) Newcomer JW, Haupt DW, Fucetola R, et al. Treatment cohort effects on insulin stimulated glucose disposal during euglycemic clamp (abstract) Biol psychiatry 2002;51:25S.

(13.) Sowell MO, Mukhopadhyay N. Cavazzoni P, et al. Hyperglycemic clamp assessment of insulin secretory responses in normal subjects treated with olanzapine, risperidone, or placebo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:2918-23

(14.) Cassidy F, Ahearn E, Carroll BJ. Elevated frequency of diabetes mellitus in hospitalized manic-depressive patients. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1417-20.

(15.) Koller E. Doraiswamy PM. Olanzapine-associated diabetes Pharmacotherapy 2002;22:841-52.

(16.) Koller E. Doraiswamy PM, Cross JT. Risperidone-associated diabetes. Diabetes, lipids and metabolism (paper presentation). San Francisco: Endocrine Society annual meeting, 2002.

(17.) Koller E, Schneider B, Bennett K, Dubitsky G, Clozapine-induced diabetes. Am J Med 2001;111:716-23.

(18.) Cavazzoni P. Deberdt W, Kwong K, et al. Pharmacoepidemiology: diabetes and antipsychotic drugs (paper presentation) Phoenix: New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit 41st annual meeting, 2001.

(19.) Gupta S, Steinmeyer C, Frank B, et al. Atypical antipsychotics: hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and EKG changes (paper presentation) Orlando: American Psychiatric Association 53rd Institute on Psychiatric Services, 2001.

(20.) Joffres MR. Hamet P, MacLean DR, L'italien GJ, Fodor G. Distribution of blood pressure and hypertension in Canada and the United States. Am J Hypertension 2001;14(11, Pt 1):1099-1105.

(21.) Austin MA. Hokanson JE, Edwards KL Hypertriglyceridemia as a cardiovascular risk factor. Am J Cardiol 1998;81(4A):7B-12B.

(22.) Mokdad AH. Bowman BA, Ford ES, Vinicor P, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States, JAMA 2001;286:1195-2001.

(23.) Fontbonne A, Eschwege E. Insulin-resistance, hypertriglyceridemia and cardiovascular risk: the Paris Prospective Study. Diabetes Metab 1991;17:93-5

(24.) Allison DB. Mentore JL, Heo M, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156(11):501-2.

(25.) Gupta S, Droney T, Al-Samarrai S, Keller P, Frank B. Olanzapine: weight gain and therapeutic efficacy. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999:19:273-5

(26.) Czbor P, Volavka J, Sheitman B, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain and therapeutic response: a differential association. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002;22:244-51.

(27.) Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Logan J, et al. Brain dopamine and obesity. Lancer 2001;357:354-7.

(28.) Reynolds GP, Zhang Z, Zhang X. Association of antipsychotic drug-induced weight gain with a 5-HT2C receptor gene polymorphism, Laurel 2002;359;2086-7.

(29.) Kinon BJ, Basson BR, Gilmore JA, Tollefson GD. Long-term olanzapine treatment: weight change and weight related health factors in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2001:62:92-100.

(30.) Nguyen CT, Ortiz T, Franklin D, et al. Nutritional education in minimizing weight gain associated with antipsychotic therapy (paper presentation). New Orleans: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2001.

(31.) Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Kysar L, et al. Novel antipsychotics: comparison of weight gain liabilities. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60:358-63.

(32.) Floris M, Lejeune J, Deberdt W. Effect of amantadine on weight gain during olanzapine treatment. Eur Neutropsychopharmacol 2001;11:181-2.

(33.) Brier A, Tanaka Y, Roychowdhury S, et al. Nizatidine for the prevention of olanzapine-associated weight gain in schizophrenia and related disorders. A randomized controlled double-blind study (paper presentation). Phoenix: New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit annual meeting, 2001.

(34.) McElroy SL, Suppes T, Keck PE, Jr., et al. Open label adjunctive topirimate in the treatment of bipolar disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2000;47:1025-33.

(35.) Koro CE, Fedder DO, L'Italien GJ, et al. An assessment of the independent effects of olanzapine and risperidone exposure on the risk of hyperlipidemia in schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:1021-6.

(36.) Littrell KH, Petty RG, Hilligoss NM, Peabody CD, Johnson CG. Educational intervention for management of antipsychotic related weight gain. J Clin Psychiatry 2003 (in press).

COPYRIGHT 2003 Dowden Health Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group