ABSTRACT

The energy-transducing cytoplasmic membrane of bacteria contains pumps and antiports maintaining the membrane potential and ion gradients. We have developed a method for rapid, single-cell measurement of the internal sodium concentration ([Na+]^sub in^) in Escherichia coli using the sodium ion fluorescence indicator, Sodium Green. The bacterial flagellar motor is a molecular machine that couples the transmembrane flow of ions, either protons (H+) or sodium ions (Na+), to flagellar rotation. We used an E. coli strain containing a chimeric flagellar motor with H+- and Na+-driven components that functions as a sodium motor. Changing external sodium concentration ([Na+]^sub ex^) in the range 1-85 mM resulted in changes in [Na+]^sub in^ between 5-14 mM, indicating a partial homeostasis of internal sodium concentration. There were significant intercell variations in the relationship between [Na+]^sub in^ and [Na+]^sub ex^, and the internal sodium concentration in cells not expressing chimeric flagellar motors was 2-3 times lower, indicating that the sodium flux through these motors is a significant fraction of the total sodium flux into the cell.

INTRODUCTION

Many species of bacteria have flagellar motors that couple ion flow across the cytoplasmic membrane to the rotary motion of flagella (1,2). The coupled ions can be either protons (H+) or sodium ions (Na+). Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, and Bacillus subtilis have proton-driven motors (3,4). The polar flagella of Vibrio alginolyticus and Vibrio cholerae have sodium-driven motors (5,6). In proton-driven motors, the membrane proteins MotA and MotB interact via transmembrane regions to form proton channels, with each MotA/MotB complex a torque-generating stator (7,8). PomA and PomB in the sodium-driven motor are homologous to MotA and MotB, respectively. The chimeric PotB7^sup E^ protein (9) has the N-terminal of PomB fused in frame to the periplasmic C-terminal of MotB, which can form functional stators with PomA. These stators (PomA/PotB7^sup E^) support sodium-driven motility in ΔmotA/motB E. coli with a swimming speed higher than the original MotA/MotB stators. To investigate the motor mechanism and its dependence on sodium-motive force (smf), we developed a method for rapid measurement of internal sodium concentration ([Na+]^sub in^) in a single E. coli cell that is compatible with simultaneous speed measurements of the flagellar motor.

[Na+]^sub in^ has been measured in E. coli by flame photometry (10), ^sup 22^Na uptake in inverted vesicles (11), and ^sup 23^Na NMR spectroscopy (12,13). Other techniques have been reported to measure [Na+]^sub in^ in eukaryotic cells, for example flow cytometry of hamster ovarian cells (14) and fluorescence spectroscopy of sea urchin spermatozoa (15). However, these methods measure ensemble averages from large numbers of cells using a static environment. For fast, dynamic single-cell measurements, we devised a method based on the sodium-ion fluorescence indicator dye, Sodium Green (14,16). E. coli are gram-negative bacteria with an outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that acts as a barrier to hydrophobic molecules such as Sodium Green. We investigated conditions for loading cells with the dye, choosing a balance between a sufficient fluorescence signal for single-cell measurements and minimal damage to the cell caused by disruption of the LPS. Utilizing low-light electron-multiplying charge coupled-device camera technology and laser fluorescence microscopy, we could make a series of up to 50 single-cell measurements of [Na+]^sub in^, each lasting 1 s, using dye-loading levels that had no detectable effect on the performance of the flagellar motor. Combining this technique with precise speed measurements using back-focal-plane interferometry of polystyrene beads attached to flagella (9,17) and fast exchange of the suspending medium (18) will allow investigation of the mechanism of coupling in the flagellar motor and of sodium energetics in E. coli. Here we demonstrate the method of single-cell [Na+]^sub in^ measurement and use it to investigate the response of [Na+]^sub in^ to external sodium concentration ([Na+]^sub ex^) in E. coli strains expressing either PomA/PotB7^sub E^, MotA/MotB, or no stator proteins.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Bacteria and cultures

Cells were E. coli strain YS34 (ΔcheY, fliC[four dots above] Tn10, ΔpilA, ΔmotAmorB) (18) with plasmid pYS11(fliC sticky filaments) and a second plasmid for inducible expression of stator proteins. Chimeric stator proteins were expressed from plasmid pYS13 (pomApotB7^sup E^), induced by isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranosid (IPTG). Wild-type stator proteins were expressed from plasmid pDFB27 (motAmotB), induced by arabinose. Cells were grown in T-broth (1% tryptone (Difco, Detroit, MI), 0.5% NaCl) containing IPTG (20 µM) and arabinose (5 mM) where appropriate at 30°C until midlog phase, harvested by centrifugation and sheared as described (8) to truncate flagella. The bacteria were washed three times at room temperature by centrifugation (2000 × g, 2 mm) and resuspended in sodium motility buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate, 85 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.0).

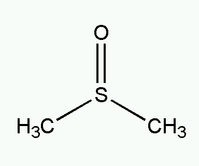

Cell loading with sodium fluorescence indicator

Cells were suspended in high EDTA motility buffer (sodium motility buffer plus 10 mM EDTA) for 10 min (to increase the permeability of the outer LPS membrane), washed three times in sodium motility buffer, and resuspended at a density of 10^sup 8^ cells/ml in Sodium Green loading buffer (sodium motility buffer plus 40 µM Sodium Green (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR)) and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Cells were washed three times and resuspended in sodium motility buffer to remove excess Sodium Green. Sodium Green was added to sodium motility buffer as a stock solution of 1 mM dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Sample flow cells

Cells were attached to polylysine-coated coverslips in custom-made flow chambers (volume ~ 5 µl), which allowed complete medium exchange within 5 s. For the speed measurement, polystyrene beads (0.97 µm diameter, Polyscience, Warrington, PA) were attached to flagella as described (8,18).

Microscopy

Cells were observed in a custom-built microscope. Sodium Green was excited in epi-fluorescence mode at 488 nm by an Ar-ion Laser (Melles Griot, Carlsbad, CA), band-pass filter set XF100-2 (Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT) and Plan Fluor 100×/1.45 oil objective (Nikon UK, Kingston-upon-Thames, UK). Images (128 × 128 pixels, ~6 × 6 µm, each frame with 1 s exposure) were acquired using a back-illuminated Electron Multiplying Charge Coupled Device (EMCCD) camera (iXon DV860-BI, Andor, Belfast, UK). The total illuminated area was (20 µm)^sup 2^, and the illumination intensity at the sample was varied in the range 7-19 W/cm^sup 2^ (±2%). A tungsten halogen lamp was used for low-intensity bright-field illumination. Motor speed was determined by back-focal-plane interferometry of polystyrene beads attached to flagella, as described (8,17). All experiments were performed at 23°C.

Sodium Green loading conditions

Fig. 2 A shows the fluorescence intensity of E. coli after different incubation times in 40 µM Sodium Green loading buffer. Each point is an average of 10 cells for which fluorescence was measured immediately after loading. We selected 30 min as the optimal loading time. Under this loading condition the fluorescence signal is >5 times the background, and measurements of flagellar rotation indicated that the motor and smf are unaffected by the dye. (The mean and standard deviation of measured speeds of a 0.97 µm bead attached to a motor were determined for each of 28 loaded and 26 nonloaded cells in 85 mM Na+. For loaded cells the average mean speed was 89 ± 6 Hz and the average speed deviation was 1.8 ± 0.6 Hz, indistinguishable from the corresponding values, 90 ± 7 Hz and 2.1 ± 0.9 Hz, respectively, for nonloaded cells.) Only a small increase in fluorescence intensity is seen for incubation times between 30 min and 50 min in 40 µM Sodium Green. For incubation times longer than 60 min, we observed differences between cell shapes in fluorescence and bright-field images, consistent with broken cells from which the cytoplasm was leaking activated fluorophores. Concentrations above 40 µM increased the number of broken cells for a given loading time >60 min. Shorter loading times and/or lower concentrations of Sodium Green gave reduced fluorescence intensity and thus more noisy measurements of [Na^sup +^]^sub in^.

Photobleaching of Sodium Green

Several processes could cause the fluorescence intensity of the same cell with the same [Na^sup +^]^sub in^ to change over time. The Sodium Green dye is converted to its acidic fluorescent form only after entry to the cell, where intracellular esterase activity cleaves off the acetate moieties. The negatively charged groups of the acidic form greatly reduce the rate of passive leakage from the cell. Continuing activation of dye during observation would lead to increasing fluorescence. Decreasing fluorescence could be caused by leakage of dye out of cells, metabolic or other chemical degradation, or photobleaching. Fig. 3 A shows the fluorescence intensity of a loaded cell in sodium buffer as a function of time during continuous illumination at an intensity of 9.8 W/cm^sup 2^. The curve can be fitted as an exponential decay with a time constant of 30 ± 0.75 s. The fluorescence intensity decay rate is proportional to illumination intensity (Fig. 3 B), indicating that the main effect in our system is photobleaching. Fig. 3 C shows a combined decay curve for data at different laser powers, illustrating that the effect of photobleaching can be described by F(x) = F^sub o^ exp(-x/x^sub o^), where x is the accumulated laser exposure and x^sub o^ = 310 ± 20 (J/cm^sup 2^)^sup -1^. All subsequent measurements of fluorescence intensity used to determine [Na^sup +^]^sub in^ were corrected for cumulative photobleaching using the formula F^sub corrected^ = F^sub raw^ exp(x/x^sub o^). Photobleaching sets a limit to the number of successive measurements that can be made on a single cell. With a typical illumination intensity of 7.35 W/cm^sup 2^, the bleaching time constant is ~50 s. Images with 1 s exposure at this illumination intensity gave fluorescence intensities five times greater than noise, which was determined by comparing successive intensities. Thus up to 50 successive measurements can be made before photobleaching causes significant deterioration of the fluorescence signal.

Calibration of internal sodium concentration

The Sodium Green fluorescence intensity was calibrated against [Na^sup +^]^sub in^ for each cell at the end of a series of measurements (Materials and Methods). The calibration method is illustrated in Fig. 4. [Na^sup +^]^sub ex^ was varied in the range 0-85 mM (Fig. 4 A), with gramicidin and CCCP present to collapse the sodium gradient at all times after 2 min. Fluorescence intensity is shown in Fig. 4 B; ~3 was required for equilibration of [Na^sup +^]^sub in^ after a change in [Na^sup +^]^sub ex^, after which the fluorescence intensity remained approximately constant. Duplicate measurements at 0 and 85 mM indicate the reproducibility of the fluorescence measurements. The steady-state fluorescence intensity was modeled well by Eq. 1 (Fig. 4 C). The dissociation constant, K^sub d^, fitted for this cell is 19.0 ± 1.0 mM, which compares well to the value of 21 mM quoted by the supplier (16).

Accuracy and error estimation

Sources of error in our measurements of [Na^sup +^]^sub in^ in single cells are as follows:

1. Random error in measurements of fluorescence intensities F. The standard deviation of successive measurements after correction forphotobleaching was typically ~5%, attributable to instrumental noise and bleaching noise. Taking the average of three consecutive readings reduces the error to the standard error of the mean, typically ~3%.

2. Errors in determining the parameters K^sub d^ and F^sub max^ by fitting calibration data. Variations in these parameters may be due to random errors in the calibration data or to sensitivity of the dye to the intracellular environment in the case of K^sub d^. The standard deviation of fitted K^sub d^ was ~9% (see Fig. 6 C). The standard deviations of F^sub min^ and fitted F^sub max^ across cells were both ~15%; however, there was considerable covariance between fluorescence intensities F from cell to cell due to variable dye loading. The standard deviation of the ratio F^sub max^/F^sub min^, which determines the contribution to the overall error in [Na^sup +^]^sub in^ (Eq. 1), was 9.9%.

Combining these errors gives error estimates for single-cell measurements of between 22% and 27% in the range [Na^sup +^]^sub in^ = 5-20 mM. The error increases dramatically at high and low values of [Na^sup +^]^sub in^, reaching 50% at [Na^sup +^]^sub in^ = 1 and 50 mM, 100% at [Na^sup +^]^sub in^ = 0.4 and 130 mM. Fortunately, the range of sodium concentrations over which Sodium Green is sensitive is similar to that found in E. coli cells under our conditions.

In vivo measurements of internal sodium concentration

The steady-state intracellular sodium concentration [Na^sup +^]^sub in^ is a balance of sodium intake and efflux. The smf contains two parts, membrane potential (V^sub m^) and a contribution from the sodium gradient (2.3 kT/e ΔpNa, where ΔpNa = log^sub 10^{ [Na+]^sub in^/[Na+]^sub ex^}, k is Boltzmann's constant, T absolute temperature, and e the unit charge), and is maintained by various metabolic processes in E. coli. Single-cell measurements of [Na+]^sub in^ allow us to determine ΔpNa under a variety of conditions. [Na+]^sub in^ reaches a steady state within 2 min after the greatest change of [Na+]^sub ex^ in this study of 1 mM-85 mM (Fig. 5 A). The shaded line in Fig. 5 A is an exponential fit with a time constant t^sub 0^ = 29 ± 9 s. Fig. 5 B shows several successive [Na+]^sub in^ measurements on a single cell expressing the chimeric flagellar motor in different [Na+]^sub ex^. We changed the external solution every 5 min and measured fluorescence just before each change. [Na+]^sub in^ measurements show good reproducibility over the time course of nearly 1 h during which this cell was observed. Fig. 5 C shows [Na+]^sub in^ versus [Na+]^sub ex^ for another cell of the same type, with the same data plotted as ΔpNa versus [Na+]^sub ex^ in Fig. 5 D.

Fig. 6, A and B, shows [Na+]^sub in^ and ΔpNa, respectively, as functions of [Na+]^sub ex^, measured as in Fig. 5, C and D, for eight individual E. coli YS34 cells expressing the chimeric flagellar motor. In 85 mM sodium, [Na+]^sub in^ was measured in the range 8-19 mM corresponding to a ΔpNa of -0.68 to -1.01 (-40 to -60 mV). The variation of ΔpNa with [Na+]^sub ex^ indicates significant but imperfect homeostasis of internal sodium concentration, with [Na+]^sub in^ varying only ~2.5-fold as [Na+]^sub ex^ varies 85-fold in the range 1-85 mM. The sign of ΔpNa reverses at [Na+]^sub ex^ between 5 and 20 mM. One interesting feature of the data in Fig. 6 A is the considerable intercell variation in the relationship between [Na+]^sub ex^ and [Na+]^sub in^. For example, values of [Na+]^sub in^ measured at [Na+]^sub ex^ = 85 mM varied >2-fold across our sample of 8 cells (Fig. 6 A), considerably larger than the estimated error of 27% for each single-cell measurement. Fig. 6 C also shows that there was no strong correlation between [Na+]^sub in^ and the fitted calibration parameters, indicating that the variation of [Na+]^sub in^ is due to true differences between individual cells rather than an artifact of the measurement procedure.

Effect of flagellar motor proteins on ΔpNa

The sodium influx through the PomA/PotB7^sup E^ stators of the chimeric flagellar motor has not been measured. However, if we assume a similar number of ions pass the motor per revolution as in the proton driven motor (19), then the sodium motor flux could be high compared to other sodium fluxes, for example through a sodium symporter (20). To investigate this possibility, we compared ΔpNa in E. coli strain YS34 expressing chimeric stator proteins, wild-type stator proteins, or no stator proteins (Fig. 7, A and B). The presence of chimeric stators resulted in an increase in [Na+]^sub in^ by a factor of 2-3 across the entire experimental range of [Na+]^sub ex^ (1-85 mM), corresponding to an increase of 0.34 (20 mV) in ΔpNa. This suggests that sodium flux through chimeric flagellar motors constitutes a considerable fraction of the total sodium flux in E. coli.

DISCUSSION

Calibration

Many experimental techniques have been developed to measure [Na+]^sub i^n. However, only fluorescence techniques are currently capable of the sensitivity necessary for accurate measurements at the level of single bacterial cells. There are two methods to determine ion concentrations using fluorescent indicators. Ratiometric methods, in which dual-wavelength measurements detect changes in fluorescence absorption or emission spectra upon ion binding, are independent of the concentration of the indicator. Monochromatic indicators such as Sodium Green, however, have spectra which change little upon ion binding and rely instead on differences in fluorescence intensity. This necessitates careful calibration to account for random variation in the concentration of indicator in the sample. Here every cell is calibrated individually after a series of fluorescence measurements, allowing accurate measurement of the response of [Na+]^sub in^ in single cells to factors such as [Na+]^sub ex^.

Photobleaching

The number of successive measurements that can be made on a single cell is limited by photobleaching. We estimated the signal/noise ratio (s/n) for fluorescence signal F as (s/n) = (F)/[the square root of](F - F^sub 0^)2, where F^sub 0^ is the exponential fit to the photobleaching curve (Fig. 3 A). Initial s/n were ~50, and after 50 successive measurements the s/n reduced only by a factor of 2. Here we used a 1 s exposure time throughout, but in practice the time resolution of our technique is limited only by the frame rate of the camera (up to ~5 kHz for subarrays large enough to image a single cell) and the intensity of the illuminating laser, which must be increased to give a large enough photon count within a single frame. Investigations of transient responses should be possible in future, making the tradeoff between high time resolution on the one hand and shorter lifetime and/or reduced s/n on the other. Subtle modifications to the technique may allow further optimization. For example, in the early stages of bleaching we might use lower exposure times to reach the s/n we need, increasing exposure times in the later stages to maintain the same s/n.

Fluorescent indicator dye

We used EDTA to increase the outer (LPS) membrane's permeability to the hydrophobic indicator dye, Sodium Green. Several different protocols for loading dye into cells were tested before our final choice, which was a short incubation with high concentrations of EDTA (10 mM) after cell growth and a subsequent short incubation with Sodium Green at low EDTA (0.1 mM). Adding intermediate concentrations of EDTA (0.5-5.0 mM) to the growth medium impaired the cell growth rate by a factor of 2. Simultaneous incubation, after growth, with high EDTA concentrations (1-10 mM) and Sodium Green, increased the proportion of slow-spinning flagellar motors, indicating that this approach damages the smf. Using our chosen protocol, we were able to load sufficient dye for accurate fluorescence measurements without any adverse effect on the smf, as assessed by flagellar rotation. Leakage or degradation of dye under these conditions was minimal, with only a 10% decrease in fluorescence intensity after 4 h for cells stored in the dark at room temperature.

Cell-to-cell variation

One important advantage of single-cell measurements is that they provide explicit information on variations between individual cells, eliminating this factor as a source of error in multicell measurements. We have demonstrated that there is considerable intercell variation in the relationship between [Na+]^sub in^ and [Na+]^sub ex^, which may be due to small-number fluctuations in cellular components such as sodium pumps or cotransporters. For example, the number of flagellar motors in one cell is likely to vary in the range 4-8 (21), which may lead to considerable variation of sodium intake.

Comparison to other measurements of [Na+]^sub in^

The dependence of [Na+]^sub in^ on [Na+]^sub ex^ has been studied in many bacteria. The relationship can be modeled as [Na+]^sub in^ = A ([Na+]^sub ex^)^sup α^, where α = 0 indicates perfect homeostasis and α = 1 indicates constant ΔpNa. These data (for E. coli YS34 expressing chimeric flagellar motors) are best described by α = 0.17 ± 0.02, implying significant but imperfect homeostasis in the [Na+]^sub ex^ range 1-85 mM. Many previous studies show imperfect homeostasis in E. coli (10), Alkalophilic bacillus (22), and Brevibacterium sp. (12). The [Na+]^sub ex^ and [Na+]^sub in^ ranges for these studies were 50-100 mM and 14-31 mM, respectively, similar to this study. Some reports have suggested that ΔpNa is constant as [Na+]^sub ex^ varied in E. coli (11,13) and in Vibrio alginolyticus (23). In these experiments the range of ΔpNa is +0.68 to -0.85 (+40 mV to -50 mV).

There are many differences between these experiments: differing strains, growth conditions, measurement sensitivity, additions of various chemicals (for example ^sup 22^Na, fluorophores, or a shift regent in NMR experiments), the timescale of experiments, and whether living cells or lipid vesicles were used. We present here a dynamic, single-cell [Na+]^sub in^ measurement with fast exchange of the extracellular medium. Previous studies have shown that the flagellar motor speed is proportional to smf (24) or pmf (25). We measured motor speed versus [Na+]^sub ex^ (Fig. 8 A) and found it to vary linearly with the corresponding ΔpNa (Fig. 8 B). If we assume that the membrane potential is between -130 and -140 mV, independent of [Na+]^sub ex^ (26,27), this indicates that speed is indeed proportional to smf under these conditions.

In summary, the monochromatic sodium fluorescence indicator Sodium Green provides a reliable single-cell measurement of [Na+]^sub in^. We saw significant intercell variation of [Na+]^sub in^ at a given [Na+]^sub ex^. [Na+]^sub in^ was measured in the range 2-20 mM and varied with [Na+]^sub ex^ to the power 0.17 ± 0.02. This corresponded to a ΔpNa of +0.68 to -0.85 (+40 mV to -50 mV), varying as the logarithm of [Na+]^sub ex^ (~0.85 units (~50 mV) per decade) and changing sign at a [Na+]^sub ex^ in the range 5-20 mM. Expression of chimeric flagellar motor proteins was associated with a two- to threefold increase in [Na+]^sub in^, corresponding to an increase of ~0.34 (~20 mV) in ΔpNa, possibly due to extra sodium influx through the chimeric motors. Future experiments will use this technique to investigate sodium bioenergetics at the single-cell level and the fundamental mechanism of the chimeric flagellar motor.

We thank Yoshiyuki Sowa for the making of the E. coli YS34 chimera strain, Jennifer H. Chandler and Stuart W. Reid for the E. coli YS34 wild-type strain, and David Blair for the gift of plasmid (pDFB27).

C.-J.L. thanks Swire Group for financial support. The research of R.B. and M.L. was supported by the combined United Kingdom Research Council via an Interdisciplinary Research Collaboration in Bionanotechnology.

REFERENCES

1. Berry, R. M., and J. P. Armitage. 1999. The bacterial flagella motor. Adv. Microbiol. Physiol. 41:291-337.

2. Berg, H. C. 2003. The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annn. Rev. Biochem. 72:19-54.

3. Blair, D. F., and H. C. Berg. 1990. The MotA protein of E. coli is a proton-conducting component of the flagellar motor. Cell. 60:439-449.

4. Shioi, J.-I., S. Matsuura. and T. Imae. 1980. Quantitative measurement of proton motive force and motility in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 144:891-897.

5. Yorimitsu, T., and M. Homma. 2001. Na+-driven flagellar motor of Vibrio. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1505:82-93.

6. McCarter, L. L. 2001. Polar flagella motility of the Vibrionaceae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:445-462.

7. Blair, D. F. 2003. Flagellar movement driven by proton translocation. FEBS Lett. 545:86-95.

8. Ryu, W. S., R. M. Berry, and H. C. Berg. 2000. Torque-generating units of the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli have a high duty ratio. Nature. 403:444-447.

9. Asai, Y., T. Yakushi, I. Kawagishi, and M. Homma. 2003. Ioncoupling determinants of Na+-driven and H+-driven flagellar motors. J. Mol. Biol. 327:453-463.

10. Epstein, W., and S. G. Schultz. 1965. Cation transport in E. coli. V. Regulation of cation content. J. Gen. Physiol. 49:221-234.

11. Reenstra, W. W., L. Patel, H. Rottenberg, and H. R. Kaback. 1980. Electrochemical proton gradient in inverted membrane vesicles from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 19:1-9.

12. Nagata, S., K. Adachi, K. Shirai, and H. Sano. 1995. ^sup 23^Na NMR spectroscopy of free Na+ in the halotolerant bacterium Brevibacterium sp. and Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 140:729-736.

13. Castle, A. M., R. M. Macnab, and R. G. Shulman. 1986. Measurement of intracellular sodium concentration and sodium transport in Escherichia coli by ^sup 23^Na nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Biol. Chem. (Tokyo). 261:3288-3294.

14. Amorino, G. P., and M. H. Fox. 1995. Intracellular Na+ measurement using Sodium Green tetraacetate with flow cytometry. Cytometry. 21:248-256.

15. Rodriguez, E., and A. Darszon. 2003. Intracellular sodium changes during the speract response and the acrosome reaction of sea urchin sperm. J. Physiol. 546:89-100.

16. Molecular Probes. The Handbook. http://probes.invitrogen.com/handbook/

17. Rowe, A. D., M. C. Leake, H. Morgan, and R. M. Berry. 2003. Rapid rotation of micron and submicron dielectric particles measured using optical tweezers. J. Mod. Opt. 50:1539-1554.

18. Sowa, Y., A. D. Rowe, M. C. Leake, T. Yakushi, M. Homma, A. Ishijima, and R. M. Berry. 2005. Direct observation of steps in rotation of the bacterial flagellar motor. Nature. 437:916-919.

19. Meister, M., G. Lowe, and H. C. Berg. 1987. The proton flux through the bacterial flagellar motor. Cell. 49:643-650.

20. Häse, C. C., N. D. Fedorova, M. Y. Galperin, and P. A. Dibrov. 2001. Sodium ion cycle in bacterial pathogens: evidence from cross-genome comparisons. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:353-370.

21. Turner, L., W. S. Ryu, and H. C. Berg. 2000. Real-time imaging of fluorescent flagellar filaments. J. Bacteriol. 182:2793-2801.

22. Hirota, N., and Y. Imae. 1983. Na+-driven flagellar motor of an Alkalophlic Bacillus strain YN-1. J. Biol. Chem. (Tokyo). 258:10577-10581.

23. Liu, J. Z., M. Dapice, and S. Khan. 1990. Ion selectivity of the Vibrio alginolyticus flagellar motor. J. Bacteriol. 172:5236-5244.

24. Sowa, Y., H. Hotta, M. Homma, and A. Ishijima. 2003. Torque-speed relationship of Na+-driven flagellar motor of Vibrio alginolyticus. J. Mol. Biol. 327:1043-1051.

25. Gabel, C. V., and H. C. Berg. 2003. The speed of the flagellar rotary motor of Escherichia coli varies linearly with protonmotive force. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:8748-8751.

26. Felle, H., J. S. Porter, C. L. Slayman, and H. R. Kaback. Quantitative measurements of membrane potential in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 19:3585-3590.

27. Castle, A. M., R. M. Macnab, and R. G. Shulman. 1986. Coupling between the sodium and proton gradients in respiring Escherichia coli cells measured by ^sup 23^Na and ^sup 31^P nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Biol. Chem. (Tokyo). 261:7797-7806.

Chien-Jung Lo, Mark C. Leake, and Richard M. Berry

Clarendon Laboratory, Department of Physics, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3PU, United Kingdom

Submitted July 25, 2005, and accepted for publication September 22, 2005.

Address reprint requests to Richard M. Berry, E-mail: r.berry@physics.ox. nc.uk.

Copyright Biophysical Society Jan 1, 2006

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved