Elderly patients living in the nursing home setting are up to five times more likely to have depression, but fewer than one fourth are adequately treated. Physicians may believe that other medical conditions are causing the depression or that other medical conditions may make treatment of depression contraindicated. In addition, there is little evidence about the optimal treatment of depression in elderly patients. Brown and associates performed a cross-sectional study and describe management of this condition.

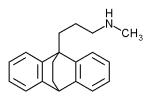

A database used by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) was the source of data for this study. All Medicaid and Medicare-certified nursing homes in Kansas, Maine, Mississippi, New York, and South Dakota were included. Medications given to each resident were recorded, and antidepressants were classified as tricyclics (amitriptyline, imipramine, doxepin, amoxapine, protriptyline, nortriptyline, trimipramine, and desipramine), tetracyclic (maprotiline), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (phenelzine, isocarboxazid, and tranylcypromine), and others (venlafaxine, trazodone, bupropion, and nefazodone).

Of the 428,055 residents included in the study, 46,677 were diagnosed with depression. The diagnosis occurred more often in women than in men and more often in non-Hispanic white patients than those with other ethnic backgrounds. One half (55 percent) of those with this diagnosis received an antidepressant. Many of these patients were given less than the manufacturer's recommended dosage, although the authors acknowledge that some of the antidepressants may have been prescribed for indications other than depression.

Patients who were 85 years of age or older were less likely to be given treatment than younger patients, and blacks were less likely to be given treatment than whites. Patients with cancer or more than six diagnosed clinical conditions were less likely to take antidepressants. On the other hand, patients with diabetes mellitus or cerebrovascular disease were more likely to receive antidepressants.

The authors concur with the recommendations of the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on Diagnosis and Treatment of Depression in Late Life, that elderly patients with depression should be given adequate dosages of antidepressants and continue taking them for an appropriate length of time to maximize the likelihood of recovery. Up to 80 percent of these patients respond well to such treatment.

Physicians should be aware that, in the elderly patient, depression may be difficult to distinguish from other conditions (such as dementia), and patients may present with symptom profiles that are different from those of younger patients. Finally, elderly patients may not have full-blown depression but, in this population, a symptom complex representing subsyndromal depression may be amenable to treatment.

COPYRIGHT 2002 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Group