String Them Up

NEW YORK, JUNE 6

Ahmed jubarah said that he did not consider himself a murderer, he was simply a man who wanted peace and freedom. That's all. He traveled extensively in his young life, including, at age 20, a voyage to Colombia, where there have been a lot of people over a lot of decades who have sought peace and freedom at gunpoint. He went then to Paterson, N.J., and on to Chicago. Later he returned to the West Bank, his native land, and joined Al-Fatah. He put an old refrigerator into a car and placed it in Zion Square in the center of Jerusalem. A timing device exploded. He killed 13 Israelis and wounded 60. He was caught and sentenced to life in prison.

That was 28 years ago.

On Tuesday, as a conciliatory gesture, General Sharon ordered his release. He had become known as Abu Sukar, or "Father of Sugar," the reference being to his daughter of that name.

How many more freedom fighters are in Israeli prisons? One hundred were released, along with the Father of Sugar. Five thousand are still in jail. The road map will almost surely call for amnesty for all of them, but the negotiators have perforce to acknowledge a problem of their own making. It is one thing to arrest and put into limbo-jail a suspect, something more than that to do so to someone responsible for terrorist killing. Israel has abjured capital punishment. On one side of the moral ledger, this is a kindly thing to do. On the other side, it is a cause of endless activity by those who argue-and fight for-the convict's release. The Israelis decades ago announced that they would not trade in captive killers. But, as quietly as they could manage, they proceeded to do so in 1994, returning some 4,000 Palestinians. It was hoped that, once released, they would pursue only pacific means of forwarding their mission, but Israeli intelligence has not revealed any figures. How many of them sought to kill again? It is unlikely that Ahmed Jubarah will place another refrigerator bomb in the center of Jerusalem. But we have heard nothing from his lips urging younger men to stop the killing.

Surely if Mr. Abbas and Gen. Sharon agree to concerted efforts to end terrorism, they should agree that anyone convicted of the crime should be executed. It would be especially effective if such executions were conducted by the country to which the terrorist professes allegiance. There have been Israeli terrorists; the massacre in Nahariya comes to mind. But of course the preponderance of them are Palestinian, and a resolution of immense consequence should be considered: Death sentences by the Arafat government for Palestinians caught contriving acts of terrorism, tried, and found guilty.

The peace-seekers need to challenge head-on recidivist acts of terrorism, and the way to do this is with dispatch and finality.

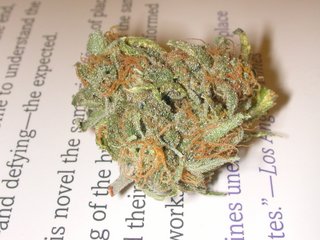

Reefer Madness

NEW YORK, JUNE 10

The experience of Ed Rosenthal of Oakland, Calif., accelerates the day when heavy dilemmas in our legal system might just force a fresh look at our marijuana laws. Presumably that will have to happen when state legislators, congressmen, and presidents are in recess, because the great enemy of sensible reform has been, of course, politicians high on righteousness.

What happened to Rosenthal was that he was convicted of marijuana cultivation and conspiracy, facing a conceivable sentence of 100 years in prison and a fine of $4.5 million. The defense attorney had been forbidden by presiding Federal District Judge Charles Breyer to advise the jury of the perspectives of the defense. The city of Oakland, instructed by a statewide proposition in 1996, had enacted an ordinance authorizing the growth of marijuana for medical use. The judge took the flat position that local laws do not override federal laws; therefore the verdict could not be influenced by the legal contradiction, and therefore the jurors shouldn't be sidetracked by hearing about it. The reasoning was identical to that of Judge George King in the case of computer guru and poet Peter McWilliams. Judge King did not permit McWilliams to base his defense on the California initiative. McWilliams died from AIDS, while awaiting sentencing, unrelieved by the marijuana that critically lessened his nausea.

Sentencing day for Rosenthal was at hand on June 5, and there was some commotion when the thought was expressed that the guilty finding could mean life in prison. One juror had told the press that if she had known such might be the consequence of a guilty finding, she, and presumably other jurors, would not have voted as they did. The day came, and Judge Breyer, perhaps with a wink of the eye, sentenced Rosenthal to one day in jail and a $1,000 fine.

Rosenthal is a full-time practitioner of resistance to marijuana legislation. He has written several books, totaling in sales over 1 million. In one of his most recent, The Closet Cultivator, he outlined how to build an indoor-marijuana-growing system impossible to detect through any method other than betrayal. When arrested, he was linked to a nearby warehouse full of the drug, ostensibly consigned for medical use. Rosenthal had been teasing the law along about as provocatively as one can do. He had a monthly radio show, and a little while before his arrest his guest was San Francisco's district attorney, Terence Hallinan, who praised efforts by medical-marijuana cooperatives and permitted himself the obiter dictum on existing laws that "the government anti-drug policy is a big lie that's supported by a thousand other lies."

Eric Schlosser of The Atlantic Monthly has published a deeply informative and readable book called Reefer Madness. He wonderfully illustrates the complexity, contradiction, and futility of extant drug laws. The marijuana laws can most directly be compared to the Prohibition-era laws, which didn't work, undermined the law, and were capriciously enforced. Pot consumption varies, but not in correlation with the laws' throw-weight. If you buy an ounce in New York State, that could bring you a fine of $100; in Louisiana, a jail sentence of 20 years.

Ed Rosenthal is quoted by author Schlosser. Will the laws in America dissipate, as they have done in Europe? He doesn't think so. "They've made the laws so brittle, one day they're going to break." The whole edifice of prohibition would come down, he predicted, "like the fall of the Berlin Wall." Schlosser nicely summarized Rosenthal's prediction. "A group of powerful, white, middle-aged men will meet in a room to discuss what to do about marijuana. And they will reach the only logical conclusion: tax it."

Like booze, some will then go on to abuse it, though with consequences less dire.

A Refreshing Exchange

NEW YORK, JUNE 17

The attorney general of Alabama is the most refreshing thing to happen to Washington since William Faulkner said the reason he wouldn't be going to President Kennedy's Nobel prize-winner party at the White House was that Washington was a long way to go for dinner. Listen to William Pryor being grilled by Senator Feingold. The senator was fishing about trying to add to Mr. Pryor's list of disqualifications to serve as judge. Wasn't Mr. Pryor associated with the Republican Attorneys General Association (RAGA), which made contributions to Republican contenders for election as attorneys general?

FEINGOLD. Will you provide to the committee a comprehensive list of RAGA's contributors and the amounts and dates of their contribution?

PRYOR. I don't have such a list, Senator.

FEINGOLD. Who does?

PRYOR. The Republican National Committee.

FEINGOLD. Will you urge them to provide that list?

PRYOR. If you need that kind of list, then you really need to seek it from them.

FEINGOLD. You oppose a disclosure of this information?

PRYOR. I'm not saying that I oppose it or I favor it.

FEINGOLD. I'm taking this as a refusal to urge the release of this information.

[In street talk, this would read: You want that? Well, stir ass and get. Don't use me as your research assistant.]

Attorney General Pryor has run into the high risk of sassing critically situated senators. Not that there was ever any possibility that Sen. Feingold would vote to confirm the nomination of Pryor to the court of appeals. The 41-year-old Pryor had given the committee an answer to the big question. He said it with a straight face. Said it as matter-of- factly as if he had been asked by the short-order cook whether he wanted his steak well done. The great question: Mr. Pryor, you once said that you thought the Supreme Court's decision in Roe v. Wade was "the worst abomination of constitutional law in our history." Do you still think that?

Oh yes, said Pryor.

When asked whether he thought that that decision had had moral consequences, he said, oh yes. He explained: "It has led to the slaughter of millions of innocent unborn children."

Does the attorney general of Alabama know nothing about governing protocols in dealing with proud liberal senators? You never say "unborn children" when referring merely to-fetuses. What you do is you tilt the language around a bit and talk about the rights of the mother. What is admirable about Mr. Pryor's personal deportment is his refusal to cavil. He came to conclusions about Roe v. Wade no different from those taken by Supreme Court justices who voted against the majority opinion in 1973. If a lawyer isn't free to believe that Roe was wrong as constitutional exegesis, he isn't free to think. The only proper concern for the Senate Committee, passing on a nomination by the president, who is given that authority by the Constitution, is whether the potential judge would enforce the law. And Pryor would do so, even laws based on opinions he thought wrong. But people who are in favor of abortion don't want anybody around courthouses who thinks abortions immoral, let alone illegal. Because of course if they are, then those in favor of abortion are supporting immoral activity. That's why they talk about women's rights (which include the right to be immoral). Get this: One senator wanted to know whether Mr. Pryor had canceled a visit to Disney World with his children, which visit would have fallen on Gay Day at Disney World.

"We made a value judgment and changed our plan and went another weekend."

To spare the kids from embarrassment? Hardly. The two girls were four and six. No. Mr. Pryor was saying to Disney, Look, if you want to celebrate Gay Day, count me out as a participant in the celebration. I'll come another day. Fair enough.

Pryor has a superb record, as lawyer and attorney general, but of course the Democrats won't vote for him, and they'll seek an Arlen Specter or two to dissent from Mr. Bush's nomination. The thought police are busy, and they're looking for a couple of Republican senators to help make the point that some thoughts are unthinkable.

-Universal Press Syndicate

COPYRIGHT 2003 National Review, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group