Although alcohol remains the primary "social lubricant," it has been joined by many newer psychoactive drugs that are used to intensify social exeriences. Because of the prevalence of these drugs at dance parties, raves, and nightclubs, they often are referred to as "club drugs." The most prominent club drugs are MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine), also known as ecstasy; gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB); flunitrazepam (Rohypnol); and ketamine (Ketalar). Table 1 (1) lists the various street names for these agents.

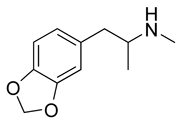

Club drugs are favored over other recreational drugs, such as marijuana, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), methamphetamine, and opiates, because they are believed to enhance social interaction. They often are described as "entactogens," giving a sense of physical closeness, empathy, and euphoria. MDMA is structurally similar to amphetamine and mescaline, which is a hallucinogen. However, it is not as stimulating or addictive as amphetamine, and is considered much less likely to cause psychosis than LSD and other potent hallucinogens. (2) GHB and Rohypnol are powerful sedative/hypnotic agents. Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic that produces a dreamy tranquility and disinhibition in small doses. Unlike opiates, these sedatives encourage sociability and seldom cause nausea.

The popularity of these club drugs is due to their low cost and convenient distribution as small pills, powders, or liquids that can be taken orally. Consequently, these drugs are popular among young persons who have been educated about the hazards of drug injection and the dangers of heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine. However, most users are unaware that MDMA is a type of methamphetamine, and incorrectly assume that substances that appear as pharmaceuticals are safe to use.

Club drugs often are taken together, with alcohol, or with other drugs to enhance their effect. Often, they are misrepresented, adulterated, or entirely substituted for another substance without the users' knowledge. These actions result in an extraordinarily high risk of unanticipated effects and overdose. (3)

In the past 10 years, there has been a generalized decrease in the use of marijuana, cocaine, and heroin in the United States, according to statistics from the Drug Enforcement Administration, the University of Michigan Monitoring the Future Study, the Columbia University National Survey of American Attitudes on Substance Abuse, the Community Epidemiology Working Group, and the Partnership for a Drug-Free America. (4) However, during this same period, the use of club drugs has dramatically increased. (5) A 2001-2002 Chicago household survey (6) of 18-to 40-year-old persons showed that 38 percent had attended a rave, and 49 percent of these had a taken a club drug. One Australian study (7) showed that only 8 percent of club-goers had not consumed any psychoactive substance.

MDMA

MDMA was developed in 1914 as an appetite suppressant, but animal tests were unimpressive, and it was never tested in humans. In 1965, psychiatrists prescribed the drug to break through psychologic defenses as an "empathy agent." By 1985, illegal laboratories were producing the drug for recreational use, and it was classified as a schedule I controlled substance.

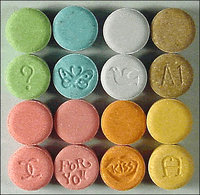

MDMA has become the most common stimulant found in dance clubs and is available at 70 percent of raves. (8) MDMA usually is sold as small tablets of variable colors imprinted with popular icons or words. A high proportion of MDMA pills are adulterated with substances such as caffeine, dextromethorphan, (9) pseudoephedrine, (10) or potent hallucinogens such as LSD, paramethoxyamphetamine (PMA),methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), N-ethyl-3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDEA), and 4-bromo-2,5-dimethoxyamphetamine (2-CB). (11) Many of these substances are "designer drugs" that are illicitly manufactured variants of pharmaceuticals and have intentional and unintentional effects. For example, MDEA ("Eve"), 2-CB, and PMA ("death") are substituted amphetamines but have primarily hallucinogenic, and often unpleasant, effects. (1)

MDMA ingestion increases the release of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine from presynaptic neurons and prevents their metabolism by inhibiting monoamine oxidase. Effects of an oral dose appear within 30 to 60 minutes and last up to eight hours. (12) A quicker onset of action can be achieved by snorting the powder of a crushed tablet. Users of MDMA describe initial feelings of agitation, a distorted sense of time, and diminished hunger and thirst, followed by euphoria with a sense of profound insight, intimacy, and well-being. (13) To further enhance the sensory effects, users often wear fluorescent necklaces, bracelets, and other accessories, and apply mentholated ointment on their lips or spray menthol inhalant on a surgical mask. Unpleasant side effects of MDMA include trismus and bruxism, which can be reduced by sucking on a pacifier or lollipop. (14)

Adverse effects of MDMA ingestion result from sympathetic overload and include tachycardia, mydriasis, diaphoresis, tremor, hypertension, (15) arrhythmias, (16) parkinsonism, (17) esophoria (tendency for eyes to turn inward), and urinary retention. (18) However, the most troublesome potential outcome of MDMA ingestion is hyperthermia (19) and the associated "serotonin syndrome." Serotonin syndrome is manifested by grossly elevated core body temperature, rigidity, myoclonus, and autonomic instability; (20) it results in end-organ damage, rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure, hepatic failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and coagulopathy. (21)

MDMA ingestion directly causes a rise in antidiuretic hormone. (22) Heat from the exertion of dancing in a crowded room coupled with the MDMA-induced hyperthermia can lead easily to excessive water intake and severe hyponatremia. (23) Neurologic effects include confusion, delirium, paranoia, headache, anorexia, depression, insomnia, irritability, and nystagmus, all of which may continue for several weeks.

Two days after ingestion of MDMA, users typically experience depression consistent with serotonin depletion, (24) which may be severe. (25) One study (26) showed that, compared with alcohol withdrawal, persons who are withdrawing from MDMA were more depressed, irritable, and unsociable. Repeated use of MDMA has been associated with cognitive deficits in animals and humans, with potentially permanent memory impairment. (27,28)

A number of products are sold legally as "herbal ecstasy." These products, available in health food stores or on the Internet, contain stimulants such as ephedra, caffeine, and guarana, with variable additions of common herbs or vitamins. (29) Users of these products may believe they are safe alternatives to MDMA, but several cases of toxic overdose have been reported from the intense stimulation of ephedrine or excessive caffeine. (30)

GHB

GHB is a derivative of the inhibitory neurotransmitter aminobutyric acid and occurs naturally in the central nervous system, where it is believed to mediate sleep cycles, body temperature, cerebral glucose metabolism, and memory. (31)

GHB was first synthesized in France in 1960 as an anesthetic. It later achieved popularity as a recreational drug and a nutritional supplement marketed to bodybuilders. (32) Nonprescription sales in the United States were banned in 1990 because of adverse effects, including uncontrolled movements and depression of the respiratory and central nervous systems (CNS). (33,34) In 2000, with 60 deaths reported from overdose and concern over its use as a "date rape" drug, GHB was reclassified as a schedule I controlled substance. (35) In 2002, sodium oxybate, a formulation of GHB, was approved for the treatment of narcolepsy and classified as schedule III. Recently, sodium oxybate has been studied as a treatment for alcohol withdrawal. (36,37)

GHB is easily manufactured from industrial chemicals. Internet Web sites offer instructions for home production and sell kits with the requisite materials. GHB is chemically related to gamma butyrolactone and 1,4-butanediol, which are metabolized in the body to GHB. (38)

The salty powder usually is dissolved in water and sold at $5 to $10 per dose. Overdose is common because the strength of the solution is often unknown. The unpleasant salty or soapy taste may be masked in flavored or alcoholic beverages. (39) Effects of GHB appear within 15 to 30 minutes of oral ingestion and peak at 20 to 60 minutes, depending on whether it is mixed with food. Toxicity is increased if taken with alcohol or other CNS depressants. (40)

GHB produces euphoria, progressing with higher doses to dizziness, hypersalivation, hypotonia, and amnesia. (41) Overdose may result in Cheyne-Stokes respiration, seizures, coma, and death. Coma may be interrupted by agitation, with flailing activity described similar to a drowning swimmer fighting for air. (42) Bradycardia and hypothermia are reported in about one third of patients admitted to a hospital for using GHB and appear to be correlated with the level of consciousness. (43) Chronic use of GHB may produce dependence and a withdrawal syndrome that includes anxiety, insomnia, tremor, and in severe cases, treatment-resistant psychoses. (44)

Rohypnol

Flunitrazepam, marketed as Rohypnol, is a potent benzodiazepine with a rapid onset. Manufactured by Roche Laboratories, it is available in more than 60 countries in Europe and Latin America for preoperative anesthesia, sedation, and treatment of insomnia. In the United States, imported Rohypnol came to prominence in the 1990s as an inexpensive recreational sedative and a "date rape" drug. (45) The tablets are sold on the street for $0.50 to $5 a piece.

In a single 1- or 2-mg dose, Rohypnol reduces anxiety, inhibition, and muscular tension with a potency that is approximately 10 times that of diazepam (Valium). Higher doses produce anterograde amnesia, lack of muscular control, and loss of consciousness. Effects occur about 30 minutes after ingestion, peak at two hours, and may last up to eight to 12 hours. The effects are much greater with the concurrent ingestion of alcohol or other sedating drugs. Some users experience hypotension, dizziness, confusion, visual disturbances, urinary retention, or aggressive behavior. (46)

Like other benzodiazepines, chronic use of Rohypnol can produce dependence. The withdrawal syndrome includes headache, tension, anxiety, restlessness, muscle pain, photosensitivity, numbness and tingling of the extremities, and increased seizure potential. (47)

Ketamine

Ketamine was derived from phencyclidine (PCP) in the 1960s for use as a dissociative anesthetic. (48) It causes anesthesia without respiratory depression by inhibiting the neuronal uptake of norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate activation in the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channel. (49) This agent can cause bizarre ideations and hallucinations--side effects that limited its medical use but appealed to recreational drug users.

Ketamine is difficult to manufacture; therefore, most of the illicit supply is diverted from human and veterinary anesthesia products. As a pharmaceutical, ketamine is distributed in a liquid form that can be ingested or injected. In clubs, it usually has been dried to a powder and is smoked in a mixture of marijuana or tobacco, or is taken intranasally. A typical method uses a nasal inhaler, called a "bullet" or "bumper"; an inhalation is called a "bump". Ketamine often is taken in "trail mixes" of methamphetamine, cocaine, sildenafil citrate (Viagra), or heroin. (50)

Effects of ketamine ingestion appear rapidly and last about 30 to 45 minutes, with sensations of floating outside the body, visual hallucinations, and a dream-like state. (51) Along with these "desired" effects, users also commonly experience confusion, anterograde amnesia, and delirium. They also may experience tachycardia, palpitations, hypertension, and respiratory depression with apnea. "Flashbacks" or visual disturbances can be experienced days or weeks after ingestion. (32) Some chronic users become addicted and exhibit severe withdrawal symptoms that require detoxification.

Treatment

Because club drugs are illicitly obtained and often are adulterated or substituted, they must be considered as unknown substances. In the ever-changing world of illegal drug distribution, Internet Web sites can be helpful in identifying the rapidly changing appearances of these substances (Table 2).

The immediate concern with the use of club drugs is cardiorespiratory maintenance. Users often present with multiple drug ingestions, which may include stimulant and depressant drugs (e.g., MDMA combined with GHB or alcohol). When the predominant symptoms are controlled, the symptoms of a second underlying drug may surface. Most hallucinogens are CNS stimulants; in overdose, patients may exhibit hyperthermia, hypertension, tachycardia, anxiety, and agitation. The risk of escape or self-injury also should be considered.

No standard treatment regimen has been identified for club drug overdose. Basic management should include cardiac monitoring, pulse oximetry, urinalysis, and performance of a comprehensive chemistry panel to check for electrolyte imbalance, renal toxicity, and possible underlying disorders (Figure 1). Precautions should be taken to prevent seizures. (19)

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

Gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal and a cathartic may be useful in acute exposures if the drug was taken orally within the previous 60 minutes. Otherwise, unless a massive dose was taken, inducing emesis is seldom effective and may increase psychologic distress. Hypertension and tachycardia generally will resolve with the management of anxiety or agitation. Severe hypertension can be treated with labetalol (Normodyne), phentolamine (Regitine), nitroprusside (Nipride), or similar agents. For agitation, benzodiazepines such as diazepam, lorazepam (Ativan), or midazolam (Versed) may be used. (52)

Hyperthermia should be treated immediately with tepid water bathing and fanning. One study (53) reported that a single tablet of MDMA resulted in fatal hyperthermia. The use of dantrolene (Dantrium) is questionable and no longer recommended. (54) Alkalinization of the urine, which usually is recommended for rhabdomyolysis, should be used cautiously because it reduces the renal clearance of amphetamine. The serotonin antagonists chlorpromazine (Thorazine) and cyproheptadine (Periactin) appear to be effective in mild to moderate cases of serotonin syndrome. (55)

There are no specific antidotes for ingestion of club drugs, except for Rohypnol, which has the antidote flumazenil. With supportive care, patients usually will recover completely within seven hours.

GHB has a rapid elimination, and the drug is cleared within four to six hours after ingestion, regardless of the dose. Intubation should be avoided unless it is absolutely necessary, because patients may become unexpectedly combative or have protracted periods of emesis. (56) The presence of trismus suggests ingestion of stimulants and makes intubation more difficult. A benzodiazepine may be given for withdrawal symptoms.

Urine or blood tests for amphetamine or methamphetamine may detect MDMA; these tests also will detect MDMA-related compounds such as 2-CB, but with decreased sensitivity. (57) A 50-mg dose of MDMA can be detected as unchanged drug in the urine up to 72 hours after ingestion. Standard toxicologic tests cannot detect GHB, but the National Forensic Laboratory (National Medical Services, 800-522-6671) will perform urinalysis for detection of GHB for a fee.

Rohypnol and its active metabolite 7-amino-flunitrazepam may be detected by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry testing up to 72 hours after ingestion. For assistance with assay in cases of suspected rape, contact Roche Laboratories (800-608-6540) for a free screening for Rohypnol. Tests for ingestion of ketamine are seldom available, but ketamine may be suspected if a toxicologic test is positive for PCP. (58)

Providing the patient and family with educational materials about specific substances may be helpful. These materials are available on many Web sites.

REFERENCES

(1.) Gahlinger PM. Illegal drugs: a complete guide to their history, chemistry, use and abuse. New York: Plume, 2004.

(2.) Cami J, Farre M, Mas M, Roset PN, Poudevida S, Mas A, et al. Human pharmacology of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine ("ecstasy"): psychomotor performance and subjective effects. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:455-66.

(3.) Drug Abuse Warning Network. Club drugs. Rockville, Md: Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2000.

(4.) Partnership Attitude Tracking Study Spring 2000. Teens in grades 7 through 12. Accessed March 17 2004 at: http://www.drugfreeamerica.org/acrobat/ pats2000full.pdf.

(5.) Koesters SC, Rogers PD, Rajasingham CR. MDMA ('ecstasy') and other 'club drugs.' The new epidemic. Pediatr Clin North Am 2002;49:415-33.

(6.) Fendrich M, Wislar JS, Johnson TP, Hubbell A. A contextual profile of club drug use among adults in Chicago. Addiction 2003;98:1693-1703.

(7.) Lenton S, Boys A, Norcross K. Raves, drugs and experience: drug use by a sample of people who attend raves in Western Australia. Addiction 1997;92:1327-37.

(8.) National Institute on Drug Abuse. The Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: overview of key findings, 2001. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan Institute for Social Research, 2002.

(9.) Graeme KA. New drugs of abuse. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2000;18:625-36.

(10.) Baggott M, Heifets B, Jones RT, Mendelson J, Sferios E, Zehnder J. Chemical analysis of ecstasy pills. JAMA 2000;284:2190.

(11.) National Institute on Drug Abuse. Epidemiologic trends in drug abuse: proceedings. Rockville, Md.: National Institute on Drug Abuse, Division of Epidemiology and Prevention Research, 2000.

(12.) Schwartz RH, Miller NS. MDMA (ecstasy) and the rave: a review. Pediatrics 1997;100:705-8.

(13.) Morland J. Toxicity of drug abuse--amphetamine designer drugs (ecstasy): mental effects and consequences of single dose use. Toxicol Lett 2000;112-3:147-52.

(14.) Smith KM, Larive LL, Romanelli F. Club drugs: methylenedioxymethamphetamine, flunitrazepam, ketamine hydrochloride, and gamma-hydroxybutyrate. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2002;59:1067-76.

(15.) Olson KR, ed. Poisoning & drug overdose. 4th ed. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill, 2004:209.

(16.) Lester SJ, Baggott M, Welm S, Schiller NB, Jones RT, Foster E, et al. Cardiovascular effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. A doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2000; 133:969-73.

(17.) Mueller PD, Korey WS. Death by "ecstasy": the serotonin syndrome? Ann Emerg Med 1998;32: 377-80.

(18.) Inman DS, Greene D. The agony and the ecstasy: acute urinary retention after MDMA abuse. BJU Int 2003;91:123.

(19.) Teter CJ, Guthrie SK. A comprehensive review of MDMA and GHB: two common club drugs. Pharmacotherapy 2001;21:1486-513.

(20.) Mason PJ, Morris VA, Balcezak TJ. Serotonin syndrome. Presentation of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine 2000;79:201-9.

(21.) Steele TD, McCann UD, Ricaurte GA. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "Ecstasy"): pharmacology and toxicology in animals and humans. Addiction 1994;89:539-51.

(22.) Henry JA, Fallon JK, Kicman AT, Hutt AJ, Cowan DA, Forsling M. Low-dose MDMA ("ecstasy") induces vasopressin secretion. Lancet 1998;351:1784.

(23.) Holmes SB, Banerjee AK, Alexander WD. Hyponatremia and seizures after ecstasy use. Postgrad Med J 1999;75:32-3.

(24.) Vollenweider FX, Gamma A, Liechti M, Huber T. Psychological and cardiovascular effects and short-term sequelae of MDMA ("ecstasy") in MDMA-naive healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 1998;19:241-51.

(25.) Curran HV, Travill RA. Mood and cognitive effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, 'ecstasy'): week-end 'high' followed by mid-week low. Addiction 1997;92:821-31.

(26.) Parrott AC, Lasky J. Ecstasy (MDMA) effects upon mood and cognition: before, during and after a Saturday night dance. Psychopharmacology 1998; 139:261-8.

(27.) Ricaurte GA, McCann UD, Szabo Z, Scheffel U. Toxicodynamics and long-term toxicity of the recreational drug, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, 'Ecstasy'). Toxicol Lett 2000;112-113:143-6.

(28.) Broening HW, Morford LL, Inman-Wood SL, Fukumura M, Vorhees CV. 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy)-induced learning and memory impairments depend on the age of exposure during early development. J Neurosci 2001;21:3228-35.

(29.) Doyon S. The many faces of ecstasy. Curr Opin Pediatr 2001;13:170-6.

(30.) Yates KM, O'Connor A, Horsley CA. "Herbal Ecstasy": a case series of adverse reactions. N Z Med J 2000;113:315-7.

(31.) Li J, Stokes SA, Woeckener A. A tale of novel intoxication: a review of the effects of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid with recommendations for management. Ann Emerg Med 1998;31:729-36.

(32.) Freese TE, Miotto K, Reback CJ. The effects and consequences of selected club drugs. J Subst Abuse Treat 2002;23:151-6.

(33.) Smith KM. Drugs used in acquaintance rape. J Am Pharm Assoc 1999;39:519-25.

(34.) Multistate outbreak of poisonings associated with illicit use of gamma hydroxy butyrate. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1990;39:861-3.

(35.) U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Gamma Hydroxybutyric Acid (GHB, liquid X, Goop, Georgia Home Boy). DEA News. March 13, 2000. Accessed March 17, 2004 at: http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/ pubs/pressrel/pr031300_01.htm.

(36.) Nimmerrichter AA, Walter H, Gutierrez-Lobos KE, Lesch OM. Double-blind controlled trial of gammahydroxybutyrate and clomethiazole in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Alcohol 2002; 37:67-73.

(37.) Addolorato G, Balducci G, Capristo E, Attilia ML, Taggi F, Gasbarrini G, et al. Gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a randomized comparative study versus benzodiazepine. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1999;23: 1596-604.

(38.) Ingels M, Rangan C, Bellezzo J, Clark RF. Coma and respiratory depression following the ingestion of GHB and its precursors: three cases. J Emerg Med 2000;19:47-50.

(39.) Eckstein M, Henderson SO, DelaCruz P, Newton E. Gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB): report of a mass intoxication and review of the literature. Prehosp Emerg Care 1999;3:357-61.

(40.) Chin MY, Kreutzer RA, Dyer JE. Acute poisoning from gamma-hydroxybutyrate in California. West J Med 1992;156:380-4.

(41.) Garrison G, Mueller P. Clinical features and outcomes after unintentional gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB) overdose [Abstract]. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 1998;36:503-4.

(42.) Dyer JE. Gamma-hydroxybutyrate: a health-food product producing coma and seizurelike activity. Am J Emerg Med 1991;9:321-4.

(43.) Chin RL, Sporer KA, Cullison B, Dyer JE, Wu TD. Clinical course of gamma-hydroxybutyrate overdose. Ann Emerg Med 1998;31:716-22.

(44.) Dyer JE, Roth B, Hyma BA. Gamma-hydroxybutyrate withdrawal syndrome. Ann Emerg Med 2001;37:147-53.

(45.) Anglin D, Spears KL, Hutson HR. Flunitrazepam and its involvement in date or acquaintance rape. Acad Emerg Med 1997;4:323-6.

(46.) Schwartz RH, Weaver AB. Rohypnol, the date rape drug. Clin Pediatr 1998;37:321.

(47.) Miotto K, Darakjian J, Basch J, Murray S, Zogg J, Rawson R. Gamma-hydroxybutyric acid: patterns of use, effects and withdrawal. Am J Addict 2001; 10:232-41.

(48.) Kohrs R, Durieux ME. Ketamine: teaching an old drug new tricks. Anesth Analg 1998;87:1186-93.

(49.) Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, Freeman GK, Delaney R, Bremner JD, et al. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans. Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994;51:199-214.

(50.) Tellier PP. Club drugs: is it all ecstasy? Pediatric Ann 2002;31:550-6.

(51.) Jansen KL. Non-medical use of ketamine. BMJ 1993;306:601-2.

(52.) Ellenhorn MJ, Barceloux DG, Ellenhorn MJ. Ellenhorn's Medical toxicology: diagnosis and treatment of human poisoning. 2d ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1997.

(53.) Dar KJ, McBrien ME. MDMA induced hyperthermia: report of a fatality and review of current therapy. Intensive Care Med 1996;22:995-6.

(54.) Watson JD, Ferguson C, Hinds CJ, Skinner R, Coakley JH. Exertional heat stroke induced by amphetamine analogues. Does dantrolene have a place? Anaesthesia 1993;48:1057-60.

(55.) Martin TG. Serotonin syndrome. Ann Emerg Med 1996;28:520-6.

(56.) O'Connell T, Kaye L, Plosay JJ 3d. Gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB): a newer drug of abuse. Am Fam Physician 2000;62:2478-83.

(57.) Christophersen AS. Amphetamine designer drugs--an overview and epidemiology. Toxicol Lett 2000; 112-113:127-31.

(58.) Weiner AL, Vieira L, McKay CA, Bayer MJ. Ketamine abusers presenting to the emergency department: a case series. J Emerg Med 2000;18:447-51.

PAUL M. GAHLINGER, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H., is an adjunct professor in the Department of Family and Preventive Medicine at the University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City, where he completed an occupational and environmental medicine residency. He received his medical degree from the University of California-Davis School of Medicine. Dr. Gahlinger also is in private practice at the Kaysville Clinic, Layton, Utah, and is a medical review officer for the Bioastronautics Research Division, NASA.

Address correspondence to Paul M. Gahlinger, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H., 225 10th Ave., Salt Lake City, UT 84103 (e-mail: paulg@aros.net). Reprints are not available from the author.

The author indicates that he does not have any conflicts of interest. Sources of funding: none reported.

COPYRIGHT 2004 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group