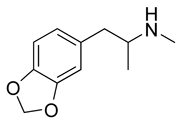

MDMA: 'Madness, not ecstasy' With a single twist on a chemical formula, "basement chemists" have sent legislators, researchers and psychiatrists into bitter battle. The latest round of controversy centers on MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine), known as "ecstasy" to some and trouble to others.

A chemical relative of methamphetamine(speed), MDMA has been hailed by users since its street debut in the late 1970s as a "safer" psychedelic drug. Free for the most part of the hallucinations produced by other psychedelics, the distilled effects, users say, leave them feeling more empathetic, more insightful and aware. Some psychiatrists have spoken in favor of its limited use in therapy, claiming that it lowers patients' defenses, improving treatment progress. (See "MDMA: Psychedelic Drug Faces Regulation," May 1985.) But there is evidence that even short-term use can cause long-term, irreversible effects on the brain, and other studies have shown MDMA's addictive potential.

Last year the federal Drug EnforcementAdministration (DEA) took "emergency" action, temporarily placing MDMA on Schedule I of the federal Controlled Substances Act. Alongside heroin, LSD and marijuana, at this level of control, producers, distributors and possessors of a drug can incur penalties of up to 15 years in jail and/or $150,000 in fines. A final decision on MDMA's permanent scheduling is expected soon.

The DEA's decision came afterconsideration of a series of biochemical and behavioral studies conducted on rats and guinea pigs by psychopharmacologists Lewis Seiden and Charles Schuster. They found that MDMA causes long-term and perhaps irreversible effects on the brain. Serotonin (a neurotransmitter involved in the regulation of sleep, sex, aggression and mood), in particular, reached an alarmingly low level.

"We've looked at rats eight weeksafter they've received MDMA," says Seiden. "Their brains are still depleted in serotonin, and there doesn't seem to be a hint that it's going to come back."

Without a government go-ahead,MDMA cannot be obtained for research or any other purpose. For therapists who had previously been using it in treatment, and for researchers wishing to study it, getting federal approval can involve a lot of paperwork and a measure of stigma, says Frank Sapienza, a chemist with the DEA. "Schedule I drugs are harder to get," he says. "And with this placement, MDMA would seem as bad as heroin or LSD."

Seiden, Schuster and others, however,see these drugs as appropriate company for MDMA. "Its therapeutic use, to me, is completely unproven," says Sidney Cohen, a former LSD researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles. "There has never been a single article published on its therapeutic value. We have to ask why."

Psychopharmacologist Ronald K.Siegel agrees. "MDMA has been promoted as a cure for everything from personal depression to alienation to cocaine addiction," he says. "It's got a lot of notoriety, but the clinical claims made for its efficacy are totally unsupported at this time."

MDMA's acute physical and psychologicaleffects resemble those produced by mescaline or MDA, another chemical relative, Siegel says. In addition to its "mind-expanding" properties, some users he has interviewed report side effects such as nausea and dizziness as well as jaw pain lasting for weeks after taking MDMA. They also use terms such as "energy tremor" and "de stressing" to describe their experiences, phrases Siegel says are euphemisms for muscle spasms and nausea and vomiting.

"I've seen people get ecstatic andI've seen people crawl into fetal positions for three days," he says. "When doses are pushed, we get madness, not ecstasy."

Based on their animal studies,Seiden and Schuster conclude that doses harmful to the brain are only about two to three times greater than the average street dose. This finding worried the DEA. "Seiden and Schuster identified a dose of MDMA close enough to street doses to concern us," Sapienza says.

The concern has spread to other researchers,who have been studying the substance for its abuse potential. Psychopharmacologist Roland Griffiths and colleagues studied baboons to see whether they would inject themselves with MDMA. When allowed to administer the drug intravenously at will, the animals did so at regular intervals. Since lab animals do not usually take to psychoactive drugs purely for their hallucinogenic effects, the baboons' behavior suggests that MDMA has some other naturally reinforcing properties, Griffiths says. Other researchers have found similar behavior in monkeys allowed access to the drug, findings they say should alert those who use MDMA recreationally or therapeutically to its abuse potential.

Although the DEA has until July 1to decide on a permanent scheduling for MDMA, theoretically that decision has already been made. In February, the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs placed the drug on Schedule I of an international treaty that theoretically binds 78 nations, including the United States, to its regulations. This decision limits the use of MDMA in those nations to medical and scientific settings under government control.

Strict regulation of MDMA, however,will not prevent the creation and abuse of chemical successors. Researchers at the National Institute on Drug Abuse have already begun to study the effects of MDE ("Eve"). And Congress is considering several bills that would prohibit the manufacture and distribution of drugs similar to those previously placed on Schedule I or II.

Without this sort of preventive approach,the MDMA story will be told and retold, with only a slight variation in format. "There's no end to the possibilities of drugs that can be engineered," Siegel says. "Designer drugs present a real law-enforcement nightmare."

COPYRIGHT 1986 Sussex Publishers, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group