Byline: C. Girish, M. Jayanthi

Anticoagulants have been in use for more than 50 years for the prevention and treatment of thromboembolic disorders. Vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin are widely used for the prevention of arterial and venous thromboembolosm in patients with atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease and following some orthopedic procedures. The drawbacks of using warfarin are the slow onset and offset of its antithrombotic action, an unpredictable and variable pharmacological response, a narrow margin of safety and numerous food and drug interactions.[1] The need for intensive laboratory monitoring to control its anticoagulant effects and the risk of bleeding has reduced the compliance of the patients. So there is need for well-tolerated, convenient, and effective alternatives to oral warfarin to improve the management of patients requiring anticoagulation therapy.

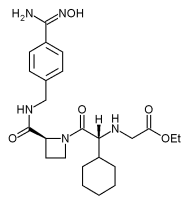

Ximelagatran is an orally active direct thrombin inhibitor. After absorption, ximelagatran is rapidly converted into its active form melagatran, a potent inhibitor of thrombin that prevents both thrombin activity and generation. Melagatran has a very poor oral absorption due to the presence of a carboxylic acid, a secondary amine and an amide residue resulting in a charged molecule at physiological pH.[2] Concomitant food intake further reduces its bioavailability. So, ximelagatran, a prodrug of melagatran was developed which has better oral absorption due to better lipophilicity and uncharged nature at intestinal pH.[3]

Pharmacokinetics

Ximelagatran, after oral ingestion is absorbed from the small intestine and undergoes rapid biotransformation, via two intermediates, ethyl melagatran and hydroxy melagatran, to melagatran. About 20% of an oral dose is absorbed. The maximum plasma concentration of melagatran is achieved 2-3 h after the oral administration with a plasma half-life of 4-5 h.[4] The drug is excreted entirely by the kidney with a mean elimination half-life of 3 h. Studies have shown that body weight, sex and ethnicity do not affect the pharmacokinetic profile of ximelagatran.[5] There is no dose adjustment required in patients with mild to moderate hepatic impairment.[6] But dose reduction or prolongation of dose interval is necessary in patients with renal disease.[7]

Pharmacodynamics

Thrombin is a serine protease involved in the formation of a stable insoluble clot. It is also involved in the activation of platelets and factors V and VIII. Ximelagatran is a potent, rapidly binding, competitive and reversible direct inhibitor of thrombin. It causes inhibition of thrombin activity, thrombin generation, platelet activation and thrombus formation. It acts on both soluble and clot-bound thrombin resulting in the prolongation of prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time and thrombin time.[8] It does not inhibit other serine proteases except trypsin.

Adverse effects

Hepatotoxicity is a major side effect noticed in patients taking ximelagatran. An elevation in alanine transferase values was observed within 6 weeks to 6 months of treatment with ximelagatran. In most of the cases, it was asymptomatic and reversible even on continuation of ximelagatran. But this warrants monitoring of liver function tests at least once a month.[9]

Interactions

The metabolism of ximelagatran is independent of the hepatic P450 system, and has no affinity to bind to plasma proteins or platelets. Hence a lower propensity to cause drug interactions.[10] Food-drug interactions have not been reported either.

Uses

<br/> *Treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism - 24 mg b.d.

Advantages

<br/> *Administered orally at fixed doses without coagulation monitoring. <br/> *Offers more predictable anticoagulant response as it is not protein cofactor-dependent. <br/> *Wider therapeutic index. <br/> *Anticoagulant action develops immediately.<br/> *No inter-subject variability.

Disadvantages

<br/> *Hepatotoxicity.

Clinical trials

An open-label SPORTIF III treatment trial found ximelagatran to be as effective as warfarin for stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation.[11] The results of SPORTIF V study showed the efficacy of fixed dose oral ximelagatran with well controlled warfarin for prevention of thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation requiring chronic anticoagulant therapy.[12] THRIVE treatment study indicated that ximelagatran was as effective as enoxaparin/warfarin for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis with similar or low rates of bleeding.[13]

In Europe, ximelagatran has been recently approved for short-term use and results of post-marketing surveillance are awaited in the near future. US FDA has not yet approved ximelagatran for concerns about hepatotoxicity.[14]

Conclusion

The novel oral anticoagulant ximelagatran has a favorable pharmacokinetic and dynamic profile as compared to warfarin. It has the potential to initiate the beginning of the end of warfarin. But the propensity to cause hepatotoxicity and the non-availability of an antidote causes concern. So the therapeutic benefits should be weighed against the risks before prescribing it to patients.

References

1. Wells PS, Howbrook AM, Crowther NR, Hirsh J. Interactions of warfarin with drugs and food: review. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:676-83.

2. Clement B, Lopian K. Characterization of in vitro biotransformation of new, orally active, direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran, an amidoxime and ester prodrug. Drug Metab Dispos 2003;31:645-51.

3. Gustafsson D, Elg M. The pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran and its active metabolite melagatran: A mini-review. Thromb Res 2003;109 Suppl 1:9-15.

4. Hirsh J, O'Donnell M, Weitz JI. New anticoagulants. Blood 2005;105:453-63.

5. Boos CJ, More RS. Anticoagulation for non-valvular atrial aibrillation - towards a new beginning with ximelagatran. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med 2004;5:3.

6. Wahlander K, Eriksson-Lepkowska M, Frison L, Fager G, Eriksson UG. No influence of mild-to-moderate hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ximelagatran, an oral direct thrombin inhibitor. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003;42:755-64.

7. Eriksson UG, Johansson S, Attman PO, Mulec H, Frison L, Fager G, et al . Influence of severe renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral ximelagatran and subcutaneous melagatran. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003;42:743-53.

8. BrightonTA. The direct thrombin inhibitor melagatran/ximelagatran. Med J Aust 2004;181: 432-7.

9. Schulman S, Wahlander K, Lundstrom T, Clason AB, Eriksson H. Secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism with the oral direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1713-21.

10. Bredberg E, Andersson TB, Frison L, Thuresson A, Johansson S, Eriksson-Lepkowska M, et al . Ximelagatran, an oral direct thrombin inhibitor, has a low potential for cytochrome P450-mediated drug-drug interactions. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003;42:765-77.

11. Olsson SB. Executive Steering Committee on behalf of the SPORTIF III Investigators. Stroke prevention with the oral direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran compared with warfarin in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (SPORTIF III): Randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003;362:1691-8.

12. Albers GW, Diener HC, Frison L, Grind M, Nevinson M, Partridge S, et al . SPORTIF Executive Steering Committee for the SPORTIF V Investigators. Ximelagatran vs warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a randomized trial. JAMA 2005;293:690-8.

13. Fiessinger JN, Huisman MV, Davidson BL, Bounameaux H, Francis CW, Eriksson H, et al . THRIVE Treatment Study Investigators. Ximelagatran vs low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis: a randomized trial. JAMA 2005;293:681-9.

14. Gurewich V. Ximelagatran-promises and concerns. JAMA 2005;293:736-9.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Medknow Publications

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group