Abstract

Multiple myeloma, which primarily affects the elderly, is rare in the head and neck. We report the case of a 71-year-old man who came to us with hoarseness, dysphagia, intermittent aspiration, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Our work-up included laboratory tests, radiographic examinations, analysis of bone marrow aspiration, and histopathologic evaluations. Cervical lymph node biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Despite treatment with chemotherapy and radiation, the patient died of his disease 6 months later.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma, a rare malignancy of plasma cells, was first described in 1950 as an abnormal production of immunoglobulins. (1) It accounts for approximately 10 to 15% of all hematologic malignancies, 1% of all malignant neoplasms in whites and 2% in blacks, and 2% of deaths from all malignancies. (1-3)

Multiple myeloma represents fewer than 2% of all head and neck cancers. (1-4) When it has been reported in the head and neck, it involved the skull base, orbit, scalp, forehead, paranasal sinuses, mandible, palate, tongue, larynx, and thyroid gland. (2-5)

The etiology of multiple myeloma is unclear. Race, genetics, geography, and exposure to radiation and occupational substances have all been implicated in its development. (1-3) Occupational risk factors include exposure to wood, metal, rubber, textiles, and petroleum. (1) Population-based studies have shown that blacks experience both a higher incidence of this malignancy and higher mortality from it. (1) Multiple myeloma is rarely seen in patients younger than 40 years; its peak incidence occurs in the sixth and seventh decades of life. (1,3)

The clinical manifestations of multiple myeloma include bone pain, anemia, hypercalcemia, and renal disease. Amyloidosis has also been seen. (3) Initial symptoms in the head and neck may include headache, confusion, irritability, diplopia, blurred vision, hearing loss, vertigo, hoarseness, dysphagia, and cranial nerve deficits. (1,3)

Case report

A 71-year-old black man came to us with a 3-month history of progressive hoarseness and dysphagia and intermittent aspiration. He denied using any medications, alcohol, or tobacco. He reported that he often applied a commercially available topical analgesic cream to relieve persistent left shoulder pain. His medical and surgical histories were unremarkable.

Physical examination revealed that he was a well-developed, well-nourished man with mild hoarseness. Findings on head, eyes, and ENT examination were normal except for the fact that his tongue deviated to the left upon protrusion and his gag reflex was diminished on the left. Indirect laryngoscopy revealed left vocal fold paralysis. Cervical adenopathy of the left posterior triangle was noted.

Laboratory testing revealed moderate normochromic, normocytic anemia (hemoglobin: 10.5 g/dl; mean corpuscular volume: 81.9 [micro][m.sup.3]; mean corpuscular hemoglobin: 26.9 g/dl; and white blood cell count: 1 1.4 x [10.sup.3]/[micro]l). His platelet count was normal. The differential count revealed 85% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, 9% lymphocytes, 3% monocytes, 3% bands, and 4+ rouleaux forms. Bence Jones proteinuria was absent. Subsequent urine immunoelectrophoresis revealed the presence of M subclass proteinuria.

Findings on fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of the neck mass were equivocal, demonstrating only abnormal cells. Computed tomography suggested fullness at the left base of the tongue. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed the presence of a mass in the left skull base that involved the clivus and the temporal bone (figure 1, A). Its epicenter was located in the area of the jugular foramen. The mass was approximately 5 cm wide, and its anteroposterior diameter was 2.5 cm. The lesion obscured the region of the left hypoglossal canal and abutted the left carotid artery. The mass indented the left cerebellar hemisphere posteriorly and extended laterally to the mastoid air cells (figure 1, B). The differential diagnosis suggested by these findings included meningioma, plasmacytoma, lymphoma, and metastatic carcinoma.

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

Direct laryngoscopy, esophagoscopy, and bronchoscopy were performed with the patient under general anesthesia. Random biopsies were taken from the nasopharynx, base of the tongue, tonsillar fossa, and pyriform sinus. The left vocal fold paralysis was noted, as well. A posterior cervical lymph node was excised and sent for frozen-section analysis. Examination of the specimen revealed sheets of atypical plasma cells with foci of normal lymphocytes (figure 2, A). Immunoperoxidase stains of the plasma cells for B- or T-cell markers were negative. Kappa and lambda preparations were inadequate for interpretation.

[FIGURE 2 OMITTED]

Bone marrow aspiration cytology revealed normal cellularity, with myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryocyte cell lines present. There were areas of patchy plasmacytosis, with increased numbers of plasma cells that had abnormal shapes and abnormal nuclei (figure 2, B). Serum electrophoresis demonstrated a monoclonal spike in the gamma globulin region. The findings of this spike and the bone marrow plasmacytosis strongly suggested a diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Except for the skull and the temporal bone, the results of a bone scan were negative.

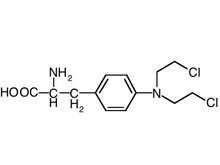

The patient was started on six cycles of vincristine, carmustine, and cyclophosphamide on the first day of treatment. After 12 weeks, he was placed on six cycles of maintenance treatment with 1 mg/kg of melphalan for 10 days and 60 mg of prednisone tapered over 5 days. He also received 4,000 cGy of radiation therapy to the neck over a 4-week period. Two months after the start of treatment, bone marrow aspiration revealed minimal change. Vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone were then given over a 5-week period. However, the patient's symptoms progressed, and he died 6 months after the initial diagnosis.

Discussion

Multiple myeloma is characterized by a proliferation of plasma cells that produce M proteins and an overproduction of myeloma protein and immunoglobulin. (1,3) A thyroid mass may arise as an enlarging neck mass with cervical lymph node involvement. Thyroid masses and cervical lymphadenopathy can be evaluated by FNAB. FNAB is also indicated for lesions in the nasal cavity, oral cavity, oropharynx, and larynx. Open biopsy may be indicated for neck and thyroid masses when FNAB is nondiagnostic. The differential diagnosis includes glomus jugular tumors, cerebellopontine angle tumor, malignant melanoma, esthesioneuroblastoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, lymphoma, and plasma cell granuloma.

The head and neck work-up includes a thorough examination, laboratory studies, and radiographic evaluation. MRI is useful in detecting dissemination of disease in the temporal bone and skull base.

The treatment of choice for previously untreated multiple myeloma is chemotherapy. The gold standard for chemotherapy is melphalan and prednisone. Even so, the long-term prognosis remains dismal, although improved survival rates have been observed with this combination. (1,2) Vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone are used to treat resistant disease.

Other treatment modalities include interferon, radiation therapy, and bone marrow transplantation. Clinical trials of interferon have demonstrated that it is effective in decreasing the production of myeloma plasma cells. (1,2) Improved response rates have been reported when interferon is combined with chemotherapy. (1,2) Radiation therapy is primarily used for palliation since multiple myeloma is not a radiosensitive disease. (1) Bone marrow transplantation has been useful in selected cases, but its application is limited. Surgery plays a limited role in multiple myeloma, although it may be useful as a means of cytoreduction, managing airway obstructions, and obtaining cervical lymph node biopsies. (5)

The prognosis of multiple myeloma is poor, and most patients die within 2 years of their diagnosis; 3-year survival is only about 10%. (1,2,5) The average survival for patients with systemic multiple myeloma is less than 1 year. (1,2,5)

References

(1.) Sheridan CA. Multiple myeloma. Semin Oncol Nurs 1996;12: 59-69.

(2.) Nofsinger YC, Mirza N, Rowan PT, et al. Head and neck manifestations of plasma cell neoplasms. Laryngoscope 1997:107:741-6.

(3.) Kearns GJ, Pogrel MA, Hanks DK, Macintosh RB. Simultaneous masses of the palate and body of mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993;51:783-6.

(4.) Schiller VL, Deutsch AL, Turner RR. Multiple myeloma presenting as extramedullary plasmacytoma of the thyroid, advanced grade II-III plasmablastic type. Skeletal Radiol 1995;24:314-16.

(5.) Reinish EI, Raviv M, Srolovitz H, Gornitsky M. Tongue, primary amyloidosis, and multiple myeloma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994;77:121-5.

From the Department of Surgery, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta.

Reprint requests: J.K. Fortson, MD, Chief of Otolaryngology, Department of Surgery, Morehouse School of Medicine, 21136 Cleveland Ave., #300, Atlanta, GA 30344. Phone: (404) 768-9350; fax: (404) 768-2530; e-mail: jkfortson1@pol.net

Originally presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery; Sept. 13-16, 1998; San Antonio, Tex.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Medquest Communications, LLC

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group