WASHINGTON -- Memantine, a leading medication for dementia in Germany, slowed the progression of moderately severe Alzheimer's disease in a 6-month U.S. multicenter trial, Dr. Barry Reisberg reported at the World Alzheimer Congress.

Memantine itself is not currently available in the United States. In fact, no treatments for this stage of Alzheimer's disease are currently approved for use in this country.

"We finally have a treatment for the most needy population of Alzheimer's patients. There are perhaps 1 million people with moderately severe disease in the United States alone, so we now may be able to help a huge number of patients to some extent [if memantine is approved]," he said at the congress, also sponsored by the Alzheimer's Association, Alzheimer's Disease International, and the Alzheimer Society of Canada.

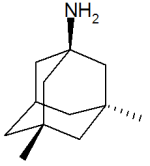

"Ours is the first study that could be considered as a basis for [Food and Drug Administration] approval" of memantine, a compound that acts on the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor system, said Dr. Reisberg, professor of psychiatry and clinical director of the Aging and Dementia Research Center at New York University, New York. The FDA generally requires "one more study of this type" to be completed before it considers approval, he noted.

In a 6-month trial, 252 patients who had moderate or moderately severe Alzheimer's disease--stage 5 or 6 on the Global Deterioration Scale--were enrolled at 32 sites throughout the United States.

Functionally, all of these patients were at stage 6, with difficulties in such basic daily life tasks as bathing, dressing, and continence. Their scores on the Mini-Mental State Exam ranged from 3 to 14, Dr. Reisberg said.

The patients were randomly assigned to receive either 10-mg tablets of memantine twice a day or placebo. They were not taking any concomitant medications known to act on cognition and were not taking agents such as neuroleptics, anxiolytics, or hypnotics.

After 6 months, the treated patients showed a significantly slower progression of disease than the patients receiving placebo on several measures of global clinical status, function in the activities of daily living and cognition.

But memantine did not reverse any already existing symptoms of Alzheimer's disease.

Memantine was safe and well tolerated, and no adverse effects were observed, he said.

Dr. Reisberg noted that his findings show that the NMDA neurotransmitter system is a promising target for other Alzheimer's treatments and perhaps for dementias and memory disorders in general. Unlike memantine, all the currently approved treatments for Alzheimer's disease in the United States act on the cholinergic neurotransmitter system.

Memantine is thought to work on the NMDA system presynaptically by modulating glutaminergic transmission and postsynaptically as an antagonist of the NMDA receptor.

The NMDA receptor is known to be involved in long-term potentiation, which occurs when the postsynaptic neuron produces a memory trace, and "it has been considered a promising target for Alzheimer's therapy" Dr. Reisberg said.

He reminded the audience that the burden of Alzheimer's disease peaks at the moderately severe stage of the disease.

"The burden on families is such that most patients are institutionalized at the end of this stage, and we can assume that the burden on patients also peaks here because behavioral disturbances reach their height at this stage," he said.

COPYRIGHT 2000 International Medical News Group

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group