Previous literature and clinical trials have established that continued illicit cocaine and crack use seriously jeopardize the effectiveness of methadone treatment (1-4). Cocaine-using methadone patients manifest multiple impairments, including continued illicit polydrug use, reduced motivation for treatment, high psychiatric comorbidity, poor interpersonal relationships, low social and economic functioning, criminal involvement, and continued HIV-risk activities (e.g., drug injection behaviors, unsafe sex) (1,2,5-8). Such multiple problems and overall low functioning make these patients difficult to engage and retain in methadone treatment (2,9). The challenge with cocaine-using methadone patients is to engage them in therapeutic activities early in treatment, which should increase the overall retention time, reduce HIV and other risk behaviors, and ultimately increase their prospects for recovery (2,6,9-12).

Since these patients often have negative and rejecting interpersonal experiences on a daily basis (e.g., avoided/feared by others, criticized by family members), it is necessary to create an accepting and positive therapeutic environment where patients can begin to address their high levels of cocaine/crack use (2). Such an approach would recognize small steps in the recovery process, utilize praise and positive reinforcement for patients' efforts, and provide tangible rewards (e.g., awards, tokens, coffee, and snacks). In addition, offering severely impaired patients enhanced treatment and services may provide them with the daily structure and activities that provide alternatives to drug-using behaviors. Previous research has demonstrated that methadone patients using large amounts of cocaine at baseline are more likely to reduce their cocaine use when exposed to a high-intensity treatment (5 x week individual and group therapy), than if they are exposed to a low-intensity intervention (1 x week cocaine group) (4).

The present study examines the addition of a behavioral contingency intervention--the TRP--to an intensive cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) protocol for cocaine and crack-using methadone patients. The TRP was based directly on a task-reinforcement paradigm, which demonstrated that rewarding patients' collateral behaviors related to individual treatment needs (e.g., addressing joblessness, finding a stable residence) produced higher cocaine abstinence rates than rewarding abstinence directly with the same incentives (13). However, the present sample was qualitatively different from Iguchi et al.'s (13) white, nonforensic, moderate cocaine using, largely employed sample; historical data from the program showed that the patients at the study clinic were at particularly high risk for drop-out from-the treatment. The authors hypothesized that a contingency plan focused on patients' individual treatment needs would enhance treatment engagement, facilitate the therapeutic alliance, and perhaps buffer patients from early drop-out.

Behavioral interventions, commonly termed "contingency management interventions" (CMIs), have demonstrated moderate efficacy in promoting abstinence with primary cocaine users and among patients in methadone maintenance (14-16). However, the success of such abstinence-based CMIs is seriously attenuated by patients' high levels of cocaine use. Despite high monetary incentives for abstinence, many cocaine-using methadone patients fail to respond to the contingency and leave treatment (17,18). Thus, the authors assumed that the present study's severely impaired sample would be more responsive to a simple task-based, rather than abstinence-based, contingency intervention.

The authors hypothesized that: (1) patients offered the TRP would engage in the simple contingency protocol. (2) The rate of successful TRP completion would be high. (3) Engagement and success in TRPs would be associated with increased retention in the study treatment and in the methadone program. (4) Engagement and success in TRPs would be associated with reductions in the use of cocaine.

This study will also profile the types of TRP tasks that patients contracted with their therapists, to help elucidate the needs of this high-risk sample.

METHODS

Participants

The sample consisted of 57 cocaine-using methadone patients, who were newly admitted to a specialized methadone clinic within a larger inner-city methadone program. The majority of patients in this clinic were referred directly from the key extended entry program (KEEP) at Rikers Island, a municipal jail, which provides methadone treatment to opiate-dependent inmates during their incarceration period (19). Early research with the Rikers KEEP population (20) and pilot work at the study site's KEEP methadone clinic showed that more than 90% of KEEP clients were cocaine users. Study eligibility was determined by patients' self-reported cocaine/crack use within the 30 days prior to admission or incarceration, if directly referred from jail. Patients who did not speak/understand English, or who demonstrated active psychotic symptoms or extremely aggressive/explosive personalities per the judgment of the clinic director (Ph.D. psychologist), were excluded from the study. Patient participation was voluntary with informed consent.

Newly admitted patients were recruited between December 1995 and July 1998 and randomly assigned to experimental or control treatment conditions. Experimental subjects received daily methadone and participated in a cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) for cocaine dependence (see Procedures), which included the TRP contingency protocol. Control subjects received regular methadone clinic services (e.g., daily methadone, drug counseling 1 x per week) and participated in the same research interview schedules as experimental subjects. Since the present study examines the process and outcomes of the TRP intervention with experimental subjects, control subjects have not been included in the analysis. Comparisons between the experimental and control conditions are being reported separately (21).

Procedures

The Enhanced Treatment Project

The study intervention including the TRP was begun on the first day of enrollment into the methadone program. Subjects participated in a 24-week, manually-driven CBT program for cocaine use that consisted of individual counseling sessions twice a week, three group therapy sessions per week, and constructive social activities (e.g., monthly outings with all active and "graduated" patients). The study staff consisted of three research therapists (two Ph.D. clinical psychologists and one M.A. psychologist) and two research assistants (M.A. psychologist and B.A.-level trained interviewer). The CBT intervention was originally based on the Matrix Model, a relapse-prevention outpatient program for primary stimulant users (22); this model was subsequently modified for work with cocaine-using methadone patients and has been described in detail elsewhere (2,23). The enhanced treatment project model emphasized small achievable steps in the recovery process and the clinical utility of praise and positive reinforcement. Individual manual sessions, such as "Homelessness," "Obtaining Entitlements," and "Grooming and Hygiene" were written specifically for the high-risk KEEP sample in order to address patients' difficulties in the tasks of daily living. Therapists rewarded subjects with a subway transportation token (value $1.50) for each individual and group therapy session they attended.

Treatment Reinforcement Plan (TRP)

A manual session describing the TRP (based on Iguchi et al.'s model) (13) was presented to new subjects during their first week of treatment in an individual therapy session. The TRP was introduced as an opportunity to earn vouchers for the completion of tasks related to immediate and long-term treatment goals. Subjects could earn $5, $10, or $15 in vouchers per week, which were redeemable in the form of transportation (tokens/metrocards), movie tickets, food coupons, or goods and services purchased in the community by their therapists. Subjects also had the option of accruing a "bank account" of up to $360 for the entire 24 weeks in treatment, which could be used to pay rent and utility bills. Subjects were not rewarded with cash.

Each week the subject and therapist would discuss the TRP at the beginning of an individual therapy session to determine or reiterate a treatment goal, which was then broken down into small units of behavior (from 1 to 3 activities per week). It was most important that the activities agreed upon were of primary importance to the subject and that he/she could feel confident about completing the assigned tasks. If subjects were unable to define goals and behaviors, the therapists would actively help subjects assess different areas of their lives (e.g., health, family, employment) to determine what they would like to improve or change. If necessary, an entire individual therapy session would be spent discussing TRP activities.

Weekly tasks were recorded either by the therapist or subject on customized TRP sheets identifying a treatment goal, from 1 to 3 targeted behaviors, incentive value, and target date for completion of the contract (typically within one week of the contract). The subject was required to bring in documentation demonstrating that the task/s had been performed (e.g., Medicaid application, doctor's bill, flyer from a self-help group), which would be presented to the therapist at the next scheduled therapy session. Together, therapist and subject would note the outcome on the TRP sheet and the incentive was immediately provided. Subjects were continually encouraged with praise and positive reinforcement for their efforts; tasks were repeated or simplified if not completed.

Measures

Data collection for all subjects included baseline, two month, and six month face-to-face interviews administered by the research assistants. Data collection consisted of open and closed-ended items addressing a variety of domains such as socio-demographics, substance use, criminal history, and treatment history. Subjects received $20 compensation for the baseline interview (e.g., transportation tokens/cards, food coupons, movie tickets), $6 compensation for a brief 2-month interview, and $20 compensation for an extensive 6-month follow-up interview.

Outcome measures included:

TRP data: The subject's immediate goal, contracted behaviors, outcome of the task/s, and amount of incentive earned.

Retention: Subjects' total number of days under methadone treatment.

Attendance: Subjects' attendance for individual and group psychotherapy sessions.

Drug Use: (a) Subjects' self-reported number of days using cocaine, heroin, alcohol, and other drugs in the past 30 days at each interview. (b) Weekly urinalysis results (see details below).

Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD): At baseline, the presence of this Axis II personality disorder was determined by the ASPD module of the Structured Clinical Interview Schedule for DSM-III-R (24).

Therapeutic Alliance: Subjects' and therapists' ratings of therapeutic alliance assessed at two months with the revised helping alliance questionnaire [HAQ; (25)].

Urinalysis

Urine specimens were collected once a week as a part of the clinic' s regular drug-testing protocol. Urine collection was random and unobserved; the lab technician immediately checked bottles by touch for warmth (the patients' bathroom had only cold running water). Urines were tested for cocaine, opiates, and methadone by enzyme immunoassay. There were no negative consequences for cocaine or opiate-positive urines. Baseline urine data were represented by the first-observed urine toxicology report, typically taken on the day of admission (intake) or during the first week of treatment. Cocaine use during treatment was measured by proportion of positive urines (number positive/number valid) across six consecutive 4-week intervals. For subjects who left methadone treatment, missing urine data were replaced with the last cocaine 4-week interval variable carried forward.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were generated for 57 subjects regarding socio-demographics, TRP activities, and the outcome variables: methadone treatment retention (total days), study therapy (CBT) attendance during months 3-6, and proportion of cocaine-positive urines during weeks 21-24 of treatment. Temporal sequencing analysis of the TRP data was performed on patients who completed the 24-week CBT protocol (N = 34) to determine the types of tasks, subjects participated in during the course of treatment. A TRP "early success" variable (number of tasks completely divided by the number of tasks contracted during the first two months of treatment) was constructed, in order to control for time in treatment, since longer retention allowed more opportunity to complete TRPs. Bivariate correlations explored the associations between TRP early success, socio-demographics, and the various outcome measures. Multivariate analyses explored the ability of TRP early success and patient background characteristics to predict various outcomes.

RESULTS

Sociodemographics and Background (Table 1)

Table 1 provides intake data for the 57 TRP participants. The majority of subjects (63%) were referred directly from the city jail; the remainder of the sample was considered "walk-ins" who had been referred to the program from various sources (e.g., needle exchange, friends/family, hospital). Twenty-five percent were female. The mean age was 40 years, ranging from 23 to 66 years of age. The majority of participants (70%) were ethnic minorities (49% Black, 21% Hispanic). Participants spent an average of $60 per day on heroin and $43 per day on cocaine/crack in the 30 days prior to admission (jail-referred subjects reported their drug activity in the 30 days prior to incarceration, while walk-in subjects reported activity prior to clinic admission). Eighty-nine percent of subjects tested positive for cocaine in the first-urine toxicology report (typically taken on the first day of admission). Additionally, 30% of walk-ins and 86% of jail-referred participants reported involvement in illegal activities in the 30days prior to admission or incarceration, respectively.

Treatment Reinforcement Plan Information (Table 2)

Participants had the opportunity to earn up to $360 (up to $15 per week) for involvement in TRP activities during the 24-week intensive therapy protocol; the actual mean total was $104, ranging from $0 to $345. Half of the participants earned $60 or greater, in vouchers. One subject failed to complete any TRP activity and earned no vouchers during treatment. The 24-week therapy period was extended according to the therapist's discretion, since some patients missed several weeks of treatment (e.g., incarceration, hospitalization, etc.). The total number of tasks set up ranged from 1 to 56 (mean = 20; SD = 14.6). The total number of tasks completed ranged from 1 to 50 (mean = 13; SD = 12.6). The overall proportion of TRP activities completed across subjects was 64%.

Table 2 lists the 18 types of tasks and completion rates for all tasks. The greatest number of tasks set up were related to therapy attendance (N = 272; 58% completed), obtaining entitlements/benefits (N = 165; 61% completed), medical/psychiatric appointments (N = 155; 70% completed), and obtaining Medicaid (N = 96; 54% completed). The highest proportion of tasks completed were related to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing/education (N = 19; 100% completed), managing money (e.g., paying bills, opening a bank account, budgeting or saving with therapists' assistance; N = 17, 94% completed), legal matters (e.g., appearing in court, reporting for community service; N = 16, 88% completed), and "other" concerns (e.g., monitoring feelings/drug cravings, getting a library card, attending couples/domestic violence counseling, etc.; N = 8, 86% completed). Tasks related to family matters (e.g., contacting estranged members, spending time with children), scheduling drug-free activities, and vocational concerns (e.g., finding employment, pursuing General Equivalency Diploma (GED)) were similarly contracted less frequently, but demonstrated high completion rates.

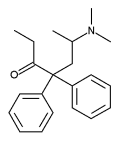

Treatment Reinforcement Plan Sequencing (Fig. 1)

Figure 1 depicts the four most frequent types of tasks set up during the 24-week treatment protocol for study subjects who completed the protocol (N = 34). Therapy attendance was the most commonly assigned task for weeks 1-12 and weeks 21-24 of treatment; medical/psychiatric appointments and tasks related to obtaining benefits were highest during weeks 13-16 and weeks 17-20, respectively. Tasks related to obtaining Medicaid and benefits drop sharply during weeks 1-12 of treatment, with benefit-related tasks increasing during the second half of treatment.

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

Outcome Analyses (Table 3)

Fifty-nine percent of participants (N = 34) completed the six-month study therapy protocol; seventy-five percent (N = 43) completed at least 3 months of study treatment. Patients were retained under methadone treatment at an average of 225 (SD = 126) days (1 year ceiling). Patients attended an average of 49 (SD = 32) group and individual therapy sessions out of a possible 120 sessions (3 group and 2 individual sessions per week, for 24 weeks). Baseline opiate-positive urines were negatively correlated (r = -0.46, p < 0.001) with TRP early success. Counselor (r = 0.44, p < 0.05) and patient (r = 0.25, p < 0.10) ratings of therapeutic alliance at 2 months (HAQ) were positively correlated with TRP early success. Black patients were more likely to be involved in successful TRP activities (r = 0.27, p < 0.05) than white or hispanic patients. White ethnicity was negatively correlated with therapy attendance (r = -0.33, p < 0.05). In addition, white ethnicity was correlated positively (r = 0.28, p < 0.05) and Black ethnicity was correlated negatively (r = -0.41, p < 0.01), with ASPD.

Table 3 shows bivariate correlations and multivariate analysis results for the main outcome variables: methadone treatment retention (up to one year), therapy session attendance during months 3-6, and proportion of cocaine-positive urines for weeks 21-24. Multiple regression analyses were conducted with all correlated predictor variables (minimum p < 0.10).

Variables associated with retention in the bivariate analysis were: TRP early success, HIV seropositive status, working prior to admission, and negative ASPD status; TRP early success and working prior to admission independently predicted methadone-treatment retention in the multiple regression analysis.

Variables associated with number of CBT sessions attended during months 3-6 were: TRP early success, age, non-white ethnicity, and cocaine-negative clinic intake urine; TRP early success and cocaine-negative intake urine independently predicted therapy attendance during months 3-6 of treatment in the multiple regression analysis.

Variables associated with cocaine-positive urines for weeks 21-24 were: lower TRP success rate, in jail prior to admission, cocaine-positive intake urine, and self-reported cocaine use at baseline. In the multiple regression analysis, TRP early success and a cocaine-negative intake urine independently predicted less cocaine use at follow-up.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that patient involvement in a simple behavioral contingency plan as an adjunct to an intensive 24-week CBT protocol enhanced treatment engagement and improved drug use outcomes with cocaine-using methadone patients. Virtually, all patients were able to successfully engage in the TRP and earn modest rewards for their contracted behaviors; only one patient failed to eam any reward. Patients' successful involvement in TRP activities during the first two months of methadone treatment was associated with longer retention in treatment, greater therapy session attendance, and lower proportion of cocainepositive urines at 6-month follow-up. Examining only subjects who completed more than two months of methadone treatment (N = 49), TRP early success still predicted longer subsequent time in treatment, and less cocaine use at 6-month follow-up.

Since engaging and retaining these patients in treatment was the primary objective of the behavioral contingency plan, it is not surprising that the most common tasks contracted between therapists and patients were related to individual and group therapy attendance. Other common contracts were related to the acquisition of entitlements (e.g., public assistance, food stamps) and Medicaid, and obtaining identification documents (e.g., birth certificate, social security card). Since the majority of patients had been released recently from jail, they frequently stated that their Medicaid and other benefits had been discontinued while incarcerated and that their relevant identification documents had been lost. Most patients were unemployed and relied on food stamps in particular to provide money for basic necessities. Re-acquiring the relevant documents and reinstating or initiating their Medicaid and other benefits was thus a priority and equivalent to basic needs for many patients. Additionally, Medicaid or an alternate type of health insurance typically covered the costs of methadone treatment for patients in the study clinic. Since the majority of patients in this study (65%) were not insured at admission, obtaining Medicaid was essential to their continuing, in treatment and in acquiring other services (e.g., health, psychiatric, dental, vision care). Tasks related to therapy attendance, obtaining Medicaid/entitlements, and acquiring documentation were accomplished by similar success rates (59% mean success).

Tasks related to more personal concerns were less frequently assigned, but demonstrated the highest completion rates. All tasks related to HIV testing/education were completed, suggesting that subjects with such tasks were motivated to learn their HIV status, improve their knowledge of HIV and risk behaviors, or (if HIV-positive) to start receiving or comply with their already established HIV treatment. Ninety-four percent of tasks related to managing money (e.g., paying bills, opening a back account, budgeting or saving) were completed; being faced with such responsibilities as paying rent/utilities, buying groceries, or providing for family members may have impelled subjects to seek contingency assistance for financial matters. Eighty-eight percent of tasks related to legal concerns (e.g., appearing in court, reporting for community service) were completed, indicating that subjects were highly motivated to address these matters, perhaps in order to avoid being incarcerated. Since the majority of patients in this study had recent criminal justice involvement, it is not surprising that they readily engaged in tasks related to legal concerns.

Regarding the temporal sequencing of tasks, therapy attendance was contracted at high rates throughout the 24 weeks, including during the final three weeks of treatment to ensure that patients would "graduate" from the enhanced treatment project and transfer to regular methadone treatment. Tasks related to obtaining entitlements and Medicaid dropped sharply by week 12 of treatment, which may reflect patients' success in acquiring these high-priority services. The increase in benefits tasks during the second half of treatment may also reflect the difficulties subjects encountered in gaining public assistance/welfare, which required various official documents and numerous personal appearances. Tasks related to medical/psychiatric appointments increased gradually over time and occurred with the greatest frequency during weeks 13-16 of treatment. This pattem indicates that medical (including dental and vision care) and psychiatric care were important treatment concerns for these patients during the intervention period. Patients were perhaps most highly motivated to complete tasks related to their personal health and hygiene, with many reporting that they had neglected their medical/psychiatric issues for many years. Additionally, the contracting of tasks related to patients' individual medical/psychiatric needs may have increased patients' overall sense of safety and facilitated the therapeutic alliance.

On the basis of Iguchi et al.'s (13) findings, we correctly anticipated that early involvement and success in TRP activities would be associated subsequently with reduced use of cocaine. Experiencing the concrete success of the intervention while being interpersonally reinforced by therapists' praise and encouragement may have bolstered subjects' feelings of self-efficacy and self-esteem, which in turn enhanced the therapeutic alliance and increased subjects' motivation to reduce cocaine use. Considering the high levels of cocaine use, criminality, and general impairment of these subjects, we regard their reductions in cocaine use as notable steps toward recovery.

Another interesting finding of this research relates to ethnicity. Similar to findings from the comprehensive Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome study (DATOS) research (26), white patients in the present study exhibited lower therapy attendance, overall retention, and ratings of therapeutic alliance. This may be accounted for by ASPD, which was positively correlated with white ethnicity and negatively correlated with black ethnicity. White patients within this study sample may be at particularly high risk for lack of therapeutic involvement and early drop-out.

The findings in this study are limited by the relatively small sample size and by the criminal justice involvement of the participants. Most patients had recent criminal justice involvement and legal concerns that may have influenced their interest in contingency contracting and overall participation in treatment. A nonforensic sample, especially one with a higher social economic status (SES) as reported by Iguchi et al. (13), may have been able to engage in more varied tasks beyond the basic needs of treatment attendance, obtaining entitlements/benefits, and attending to medical/psychiatric problems. The association between employment history and clinic retention supports this interpretation. Another important limitation is that there was no control group in this study, since the TRP was embedded in the CBT protocol; thus, the efficacy of the TRP as an independent intervention cannot be determined. Since we contracted very few participants for drug-free urines, we were unable to compare the efficacy of our task-based contingency with an abstinence-based approach. In addition, although 98% of patients were able to engage in the TRP, 25% of the sample (N = 14) had dropped out of the methadone clinic by 3 months. Despite a nonpunitive and reinforcement-rich treatment environment (2), a substantial number of patients still left treatment prematurely. It may be surmised that such early deserters lacked even a minimum of readiness for treatment (25); clearly, additional methods of engaging and retaining early treatment deserters must be explored. Alternatively, an increasing schedule of voucher delivery offering higher monetary rewards might have been more effective for engaging and retaining ambivalent patients (16,17). Future research should elucidate the efficacy of task-based contingency management interventions (CMIs) with varying schedules, magnitude of reward, and duration of reinforcement.

In the event of limited or in the absence of clinic funds to reward patients materially for contracted behaviors, some less-costly alternatives to individual rewards are suggested. Counselors may adhere to the contracting process of identifying patients' treatment goals, elucidating the behavioral "steps" required, exploring any anticipated difficulties patients may have in execution, reassessing goals and contracts if necessary, and encouraging and praising patients throughout the process. Previous research has demonstrated that simple praise and public acknowledgement of accomplishments has a positively reinforcing effect on patients' behaviors and engagement in treatment (2,27). Charting patients' treatment progress and counseling attendance on a posted bulletin board with stars and pictures may provide strong motivation for patients to remain engaged in treatment and in behavioral contracting (27). Patients may be rewarded in a group setting with certificates of achievement for attaining various treatment goals, including counseling attendance. Completion of behavioral contracts may warrant the provision of clinic privileges (e.g., take-home dosages, additional/specialized counseling services), which may be determined by the clinic staff. Finally, the use of a lottery system in which patients earn tickets for the completion of contracts (and thus, more chances to win low-cost prizes in a monthly group drawing), has encouraged behavioral change (28).

In conclusion, the study has demonstrated that a simple, task-based contingency intervention in conjunction with an intensive CBT protocol for cocaine abuse, is effective for engaging and retaining high-risk methadone patients. According to patients' most-urgent treatment needs, they contracted and were rewarded for therapy attendance and for working to acquire basic services (e.g., entitlements, medical/psychiatric care). Additionally, patients had the most success in completing tasks related to HIV testing/education, managing money, and legal problems. Such basic treatment concerns should be considered for all methadone patients, but are of particular importance for patients with high levels of cocaine/crack use and multiple impairments. While most methadone maintenance clinics lack the financial resources to reward patients for their involvement in treatment, it may be very useful for counselors to formally address patients' behaviors and needs at the micro-level, while maintaining an encouraging and nonpunitive stance towards their recovery efforts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was funded by grant number ROI DA06959 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (PI=S. Magura). Clinical work was carried out at the Narcotics Rehabilitation Center (NRC) KEEP program, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY, USA. The authors are indebted to: Barry Stimmel, M.D., Executive Director of the NRC for his support; Sy Demsky, Phillip Paris, Victor Sturiano, Mitchell Bradbury, and the entire staff at the NRC for their participation in the study. The authors also wish to thank Martin Iguchi (TRP consultant), Carol Moorer (Research Assistant), Rhea Greenberg, Bryan Fallon, Christopher Leggett (Research Therapists), Michal Seligman, and Leonard Handelsman (Clinical Supervisors).

This research was conducted in part while the corresponding author was a pre-doctoral fellow in the Behavioral Sciences Training in Drug Abuse Research Program sponsored by Medical and Health Research Association of New York City, Inc. and National Development and Research Institutes, Inc. with funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5 T32 DA07233-09).

REFERENCES

(1.) Condelli, W.S.; Fairbank, J.A.; Dennis, M.L.; Rachal, J.V. Cocaine Use by Clients in Methadone Programs: Significance, Scope, and Behavioral Interventions. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1991, 8, 203-212.

(2.) Foote, J.; Seligman, M.; Magura, S.; Handelsman, L.; Rosenblum, A.; Lovejoy, M. An Enhanced Positive Reinforcement Model for the Severely Impaired Cocaine Abuser. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1994, 11 (6), 525-534.

(3.) Kolar, A.F.; Brown, B.S.; Weddington, W.W.; Ball, J.C. A Treatment Crisis: Cocaine Use by Clients in Methadone Maintenance Programs. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1990, 7, 101-107.

(4.) Rosenblum, A.; Magura, S.; Palij, M.; Foote, J.; Handelsman, L.; Stimmel, B. Enhanced Treatment Outcomes for Cocaine-Using Methadone Patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999, 54, 207-218.

(5.) Hunt, D.; Spunt, B.; Lipton, D.; Goldsmith, D.S.; Strug, D. The Costly Bonus; Cocaine Related Crime Among Methadone Treatment Clients. Adv. Alcohol Subst. Abuse 1986, 6, 107-122.

(6.) Magura, S.; Kang, S.Y.; Nwakeze, P.C.; Demsky, S. Temporal Patterns of Heroin and Cocaine Use Among Methadone Patients. Subst. Use Misuse 1998, 33 (12), 2441-2467.

(7.) Magura, S.; Siddqi, Q.; Freeman, R.; Lipton, D.S. Cocaine Use and Help-Seeking Among Methadone Patients. J. Drug Issues 1991, 21, 629-645.

(8.) Bux, D.A.; Lamb, R.J.; Iguchi, M.Y. Cocaine Use and HIV Risk Behavior in Methadone Maintenance Patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1992, 29, 263-268.

(9.) Broome, K.M.; Simpson, D.D.; Joe, G.W. Patient and Program Attributes Related to Treatment Process Indicators in DATOS. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999, 57, 127-135.

(10.) Goldstein, M.F.; Deren, S.; Magura, S.; Kayman, D.J.; Beardsley, M.; Tortu, S. Cessation of Drug Use: Impact of Time in Treatment. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2000, 32 (3), 305-310.

(11.) Rowan-Szal, G.A.; Joe, G.W.; Hiller, M.L.; Simpson, D.D. Increasing Early Engagement in Methadone Treatment. J. Maint. Addict. 1997, 1 (1), 49-61.

(12.) Simpson, D.D.; Joe, G.W.; Rowan-Szal, G.A.; Greener, J.M. Drug Abuse Treatment Process Components That Improve Retention. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1997, 14, 565-572.

(13.) Iguchi, M.Y.; Belding, M.A.; Morral, A.R.; Lamb, R.J.; Husband, S.D. Reinforcing Operants Other Than Abstinence in Drug Abuse Treatment: An Effective Alternative for Reducing Drug Use. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 65 (3), 421-428.

(14.) Griffith, J.D.; Rowan-Szal, G.A.; Roark, R.R.; Simpson, D.D. Contingency Management in Outpatient Methadone Treatment: A Meta-Analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000, 58, 55-66.

(15.) Higgins, S.T.; Budney, A.J.; Bickel, W.K.; Foerg, F.E.; Donham, R.; Badger, G.J. Incentives Improve Outcome in Outpatient Behavioral Treatment of Cocaine Dependence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1994, 51, 568-576.

(16.) Silverman, K.; Higgins, S.T.; Brooner, R.K.; Montoya, I.D.; Cone, E.J.; Schuster, C.R.; Preston, K.L. Sustained Cocaine Abstinence in Methadone Maintenance Patients Through Voucher-Based Reinforcement Therapy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1996, 53, 409-415.

(17.) Bigelow, G.E.; Brooner, R.K.; Silverman, K. Competing Motivations: Drug Reinforcement vs. Non-Drug Reinforcement. J. Psychopharmacol. 1998, 12 (1), 8-14.

(18.) Silverman, K.; Wong, C.J.; Umbricht-Schneiter, A.; Montoya, I.D.; Schuster, C.R.; Preston, K.L. Broad Beneficial Effects of Cocaine Abstinence Reinforcement Among Methadone Patients. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 66 (5), 811-824.

(19.) Magura, S.; Casriel, C.; Goldsmith, D.S.; Lipton, D.S. Contracting with Clients in Methadone Treatment. J. Contemp. Soc. Work 1987, 68 (8), 485-493.

(20.) Magura, S.; Rosenblum, A.; Lewis, C.; Joseph, H. The Effectiveness of In-Jail Methadone Maintenance. J. Drug Issues 1993, 23 (1), 75-95.

(21.) Magura, S.; Rosenblum, A.; Fong, C.; Villano, C. Treating Cocaine-Using Methadone Patients: Predictors of Outcomes in a Psychosocial Clinical Trial. Substance Use and Misuse (in press).

(22.) Rawson, R.A.; Obert, J.L.; McCann, M.J.; Smith, D.P.; Scheffey, E.H. The Neurobehavioral Treatment Manual: A Therapist Manual for Outpatient Cocaine Addiction Treatment; The Matrix Center: Beverly Hills, CA, 1989.

(23.) Rosenblum, A.; Magura, S.; Foote, J.; Palij, M.; Handelsman, L.; Lovejoy, M.; Stimmel, B. Treatment Intensity and Reductions in Drug Use for Cocaine-Dependent Methadone Patients: A Dose-Response Relationship. J. Psychoact. Drugs 1995, 27, 151-159.

(24.) Spitzer, S.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Gibbon, M.; First, M.B. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1992, 49, 624-629.

(25.) Luborsky, L.; Barber, J.P.; Siqueland, L.; Johnson, S.; Najavits, L.M.; Frank, A.; Daley, D. The Revised Helping Alliance Questionnaire (Haq-II). J. Psychother. Pract. Res. 1996, 5, 260-271.

(26.) Joe, G.W.; Simpson, D.D.; Broome, K.M. Retention and Patient Engagement Models for Different Treatment Modalities in DATOS. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999, 57, 113-125.

(27.) Rowan-Szal, G.; Joe, G.W.; Chatham, L.R.; Simpson, D. A Simple Reinforcement System for Methadone Clients in a Community-Based Treatment Program. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1994, 11 (3), 217-223.

(28.) Petry, N.M.; Petrakis, I.; Trevisan, L.; Wiredu, G.; Boutros, N.N.; Martin, B.; Kosten, T.R. Contingency Management Interventions: From Research to Practice. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158 (5), 694-702.

Cherie L. Villano, Andrew Rosenblum, * Stephen Magura, Chunki Fong

Institute for Treatment and Services Research, National Development and Research Institutes, Inc., 71 West 23rd St., 8th Floor, New York, NY 10010

* Corresponding author. E-mail: rosenblum@ndri.org

COPYRIGHT 2002 Marcel Dekker, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group