Q Our laboratory has received requests from the local police department and the department of social services to perform drug testing on children who are picked up from meth houses. The testing is for medical treatment only, not legal purposes. I was under the impression that these children absorb the drugs in their hair, skin, and nails but rarely test positive in urine samples.

Please advise on the specimen of choice for testing children for exposure to drugs. Also, what are the medical problems related to exposure, and is testing for a drug appropriate? Would a liver profile be a better screen because of the effects of the chemicals used to manufacture methamphetamine?

A This question presents several issues. The first is a legal one. On whose authority will you be doing the testing? In many states, medical laboratory testing can only be ordered by a physician, and results can only be reported to a physician. Some states require informed consent from an individual if drug-of-abuse testing is going to be performed. Be sure that you have competent legal advice before proceeding with testing requested by police or social service agencies.

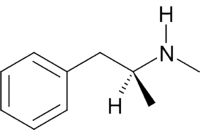

The next question is whether the children were exposed to methamphetamine users or methamphetamine manufacturing. Acute methamphetamine poisoning usually results in neurological problems such as CNS stimulation, anxiety, hyperactivity, hyperpyrexia, hypertension, abdominal cramps, nausea, and vomiting. Chronic ingestion is similar. Liver or kidney damage is not a feature of exposure to methamphetamine. (1,2)

The problems caused by exposure to methamphetamine manufacturing labs are very different. A large variety of hazardous and toxic chemicals are associated with methamphetamine manufacture. These include solvents such as xylene, acetone, trichloroethane, or toluene; caustics such as anhydrous ammonia, hydrochloric acid, or sulfuric acid; and metals and salts such as red phosphorus, iodine, or sodium metal. All of these can cause failure of the lungs, liver, or kidneys. (1,2)

A number of guidelines exist for dealing with children found at methamphetamine lab sites. These recommend that children be assessed by medically trained personnel to determine whether medical care is necessary. The most important part of the assessment is obtaining a thorough history to determine the extent of possible exposure and the chemicals used in the lab. If medical care is required, a protocol such as that in the California Drug Endangered Children Resource Center's "Medical Protocols for Children Found at Methamphetamine Lab Sites" should be followed. (3) The Oregon protocol (1) suggests that a urine methamphetamine assay be performed within 48 hours for children with no signs of toxicity. A sensitive assay capable of detecting methamphetamine at the lower levels of quantitation (50 ng/mL) is needed to detect incidental drug exposure. Other tests to be considered include a CBC and renal- and liver-function tests. None of the protocols mentions tests of hair or nails.

References

1. Oregon Department of Human Services. Children in methamphetamine "labs" in Oregon. CD Summary. August 12, 2003. Available at: http://www.dhs.state.or.us/publichealth/cdsummary/2003/ohd5216.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2005.

2. National Drug Intelligence Center. Information bulletin: children at risk. July 2002. Available at: http://www.usdoj.gov/ndic/pubs1/1466/. Accessed March 28, 2005.

3. California Drug Endangered Children Resource Center, Medical protocols for children found at methamphetamine lab sites. Available at: http://www.doh.wa.gov/ehp/ts/CDL/CA-DEC-Medical%20Protocol.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2005.

--Daniel M. Baer, MD

Professor Emeritus

Department of Pathology

Oregon Health and Science University

Portland, OR

Daniel M. Baer, MD, is professor emeritus of laboratory medicine at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, OR, and a member of MLO's editorial advisory board.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

COPYRIGHT 2005 Nelson Publishing

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group