INTRODUCTION

In the past decade South Africa has consistently had one of the highest rates of recorded homicide in the world, and other categories of both violent and property crime have been recorded at similarly high levels (1). In the first 9 months of 2001, for example, rates of murder were estimated to be 33.3 cases per 100,000 population, rape 83.5 cases per 100,000, and housebreaking (residential) 493.9 cases per 100,000 (2). Of the over 1.8 million cases reported during this period, "other thefts," assault, and housebreaking accounted for nearly 60% of all serious crime reported (2). While the incidence of most serious crimes appears to be either stabilizing or decreasing, the incidence of crime remains unacceptably high and is a serious threat to emerging democracy in this country.

Understanding the reasons behind crime is important in directing crime prevention efforts. A variety of reasons have been given for the high crime rate in South Africa, including the period of political transition, the culture of violence that resulted from the period of political oppression, the proliferation of firearms, the growth of organized crime, South Africa's youthful population, rapid urbanization, and a weak criminal justice system. Internationally, there has been an increasing body of research highlighting the drug-crime nexus (3-9). These studies use different data collection instruments, including police arrest records, self report measures, and urine tests, and focus on a wide variety of study populations, including general populations, arrestees, incarcerated prisoners, emergency department admissions, and mortuary cases. Specifically, such studies suggest that in addition to offenses specifically defined by the use of alcohol or drugs (e.g., drug dealing, drug possession, or driving a vehicle under the influence of alcohol or drugs), offenses may be committed in which the pharmacological effects of alcohol or other drugs contribute to the commission of the offense (e.g., by increasing aggression, promoting recklessness, distorting perceptions, or by decreasing inhibitions). Offenses may also be motivated by the user's need for money or goods to support continued use. Some offenses also are connected to the drug distribution itself (e.g., crimes associated with turf wars, collection of debts, or vigilantism).

The U.S. National Institute of Justice's Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM) program has done much to highlight the nature and extent of the relationship between drugs and crime. The ADAM program currently collects quarterly drug-use data from booked arrestees in 35 sites in the United States, and employs both interviews and drug testing via urinalysis. In 1999, in over 27 of 34 ADAM sites, more than 60% of adult male arrestees tested positive for one of five drugs (cocaine, cannabis, methamphetamine, opiates, and phencyclidine). For female adult arrestees the median rate for use of any drug was 67% (8).

In South Africa, while there has been a moderate amount of research on the link between alcohol use and intentional injuries and homicide (10,11), there has been a paucity of research on the link between other drugs and crime. Apart from a single prison study that found that 46% of prisoners or parolees reported using drugs at the time of, or just prior to, the offense for which they were incarcerated (12), the only information has come from police statistics on drug dealing and possession, forensic reports from mortuaries on alcohol/drug-related deaths or on the presence of alcohol/drugs in body fluids of persons who have died from non-natural causes, and statistics on driving under the influence of alcohol.

The aim of the research described in this paper is to address the lack of information on the drug-crime nexus in South Africa by studying recent arrestees using the approach used in the U.S. ADAM studies. Specific objectives included 1) gaining a greater understanding of the relationship between alcohol and drug use and crime in South Africa, and 2) using the information gained to inform health, crime, and drug prevention policy and programs.

METHODS

Study Design and Sample

The study took the form of a series of panel (cross-sectional) surveys conducted in three urban sites in South Africa (Cape Town, Durban, and Johannesburg) at police holding cells. These are the largest cities in three provinces with the highest proportion of serious reported crime per capita (2). The data presented below relate to the third phase of a three-phase study conducted at the three sites 6 months apart starting in August/ September 1999 (Phase 1) and concluding in August/September 2000 (Phase 3). Police stations in each site were chosen because of the large number of arrestees flowing through each station on an annual basis and because they represent distinct communities of interest.

All arrestees, both males and females 18 years of age or older who were in the eight holding cells during the 2-3-week study period (regardless of offense category), were considered for inclusion until the set sample quota was reached. To account for those arrestees who were not interviewed the data were weighted (see below). A total of 1050 adult arrestees were interviewed (out of 1058 who were approached) and 95% agreed to provide a urine sample for drug screening (see Table 1). Arrestees who were deemed unfit due to extreme intoxication from the use of alcohol, drugs, or medications and persons who were considered at the time of the interview to be so mentally ill or violent as to put the interviewers' safety at risk, were excluded from the survey. Only arrestees who had been detained for less than 48 hours were included in the study.

Procedures (and Protection of Human Subjects)

Interviews were conducted in secure facilities within police holding cells and security was provided by police officers who remained in the vicinity, but out of hearing of the interview. Interviewers were civilian staff working for a private research company, DRA Development. Interviewers were trained by staff from the Medical Research Council and the Institute for Security Studies over several days prior to the start of each phase. Prior to the first phase more extensive training was given to interviewers by personnel involved in the U.S. ADAM study. The participation of arrestees was voluntary and based on informed consent. Anonymity was assured. The consent form indicated that arrestees would not be prejudiced should they decline to take part in the study. Interviews took 30-40 minutes to complete. The questionnaire was linked to the urine specimen using a numbering system. Specimens were stored in cooler boxes, transferred to a refrigerator at the end of an interview shift, and shipped to a pathology laboratory for analysis within 3-4 days of collection. Approval to conduct the 2-year study was granted by the Medical Research Council's Ethics Committee in October 1998.

Measurement

Two data collection tools were employed, a questionnaire and urinalysis. A 10-page (400-item) questionnaire was developed based, on a U.S. questionnaire developed by the National Institute of Justice for the U.S. ADAM programme and was modified for local conditions. There were 11 sections: administrative information (completed prior to interview), demographic information, source of income, arrest history, current arrest information, profile of substance use, purchasing of drugs, other drugs experienced, information about new drugs on the streets, firearms and perceptions of crime, and HIV/AIDS and sexual health. The instrument was piloted and changes were instituted to make the questionnaire more user-friendly and understandable.

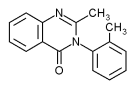

A total of six drugs were tested for, using the Enzyme-Multiplied Immunoassay Testing (EMIT) system: amphetamines (methamphetamine), cannabis, cocaine, opiates, benzodiazepines, and methaqualone (Mandrax). The urinalysis was qualitative, and no attempt was made to obtain a specific quantitative estimate of the amount of drug metabolites in the urine. The following cut-offs were employed: 50 ng/mL for cannabis, 300 ng/mL for opiates cocaine, benzodiazepines, and methaqualone, and 1000 ng/mL for amphetamines. Samples testing above these cut-off levels were deemed to be positive. No confirmatory analyses were carried out to determine specific types of opiates, amphetamines, and benzodiazepines. It should be noted that the metabolites for cannabis (tetrahydrocannabinol) remain in the urine for up to 10 days with daily use and up to 36 days with chronic heavy use, whereas metabolites for other drugs remain in the urine for 2-3 days (13).

Data Analysis (and Weighting)

In order to improve the generalizability of the data and to account for arrestees who were not interviewed, cases were weighted by the actual flow of arrestees through the cells during the days data were collected at each police station. This information was obtained from the police cell registers. Data were specifically weighted by police station and major offense category (violent offenses, property offenses, drug/alcohol offenses, and other offenses). In reality this had very little effect on prevalence or other estimates (typically less than 1% difference). Data analysis comprised mainly of frequency analyses and cross-tabulations. To assess statistical significance chi-square tests of association and confidence intervals are provided. Analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Version 9).

RESULTS

Demographic Data and Offenses

Table 2 gives the basic sociodemographic characteristics of the sample of arrestees. The majority of the sample comprised males under the age of 30. Across sites between 65% and 73% of arrestees sampled were single and between 11% and 29% had graduated from high school. Table 3 gives a breakdown of the offenses for which the subjects were arrested. Violent offenses comprised murder, attempted murder, assault, weapons-related charges, rape and attempted rape, robbery, and other violent crimes such as kidnapping, child abuse, and bomb threats. The property offenses included shoplifting, housebreaking, motor vehicle theft and other thefts, as well as arson, and trespassing. Drug/alcohol-related offenses included arrests for dealing in, or possession of, drugs and alcohol-related offenses that included driving under the influence and being drunk and disorderly. The miscellaneous offenses category comprised of arrests for illegal immigration, prostitution, obstructing police, public indecency, reckless driving, etc. The majority of arrests made were for violent or property crimes; however, a substantial number of persons were arrested for illegal immigration in Johannesburg.

Urinanalysis

All Participants

For all sites combined, 45.3% of arrestees tested positive for at least one substance, with 39.2% testing positive for cannabis, 19.4% testing positive for Mandrax (methaqualone), and 4.9% testing positive for cocaine. Table 4 shows that overall and for each of the sites separately, cannabis use was the most common drug detected in the urine of arrestees, followed by Mandrax, cocaine, and benzodiazepines. Very low levels (< 3%) of other drugs were detected.

By Site

In order to test for differences between the three sites, 95% confidence intervals were fitted around the point prevalence estimates (Table 4). The percentage of arrestees testing positive for at least one drug and for cannabis was significantly higher in Cape Town and Durban as compared to Johannesburg. Furthermore, the percentage of arrestees testing positive for either Mandrax or benzodiazepines was higher in Cape Town than in either of the other two sites. Overall, 55.9% of arrestees in Cape Town, 50.3% in Durban, and 29.3% in Johannesburg tested positive for at least one drug.

By Gender, Age, Race, and Socioeconomic Status

Table 5 shows that the percentage of male arrestees testing positive for any drug and selected drugs was greater than for female arrestees for all drugs except cocaine, amphetamines, and opiates. Persons in the age group 26 to 30 years were less likely to have any drug in their urine than the other age categories. Arrestees aged 20 years and younger were the group having the highest proportion of persons testing positive for at least one drug (mainly cannabis and/or Mandrax). African arrestees were less likely to have a drug in their urine than arrestees from other race groups. Whites were the race group with the highest percentage testing positive for at least one drug (66.9%)--mainly cocaine or cannabis, although the number of white arrestees was low (n = 17). Coloreds were the group with the highest proportion of arrestees testing positive for Mandrax, and white arrestees were the group with the highest proportion of arrestees testing positive for cocaine and opiates. The terms "White, Black, Asian/Indian, and Colored" refer to demographic markers used in South Africa and do not signify inherent characteristics. These markers were chosen for their continued significance as proxies for a range of sociocultural characteristics. The demographic characteristics of substance users are important as accurate user profiles assist in identifying vulnerable sections of the population and in planning effective prevention and intervention programs.

By Suburb

Urinalysis by police station showed that in the CR Swart, Hillbrow, and Sea Point police station samples 8.1%, 8.3%, and 13.5%, respectively, of arrestees tested positive for cocaine, whereas no arrestees tested positive for this substance in Khayelitsha, Kempton Park, and Jabulani (Table 6). The use of Mandrax appears to be far more common in areas such as Mitchells Plain and Phoenix than in the other sites. The percentage of arrestees testing positive for any drug was significantly greater in Mitchells Plain and Sea Point as compared to Khayalitsha, Kempton Park, Hillbrow, and Jabiulani. In addition, the percentage of arrestees testing positive for any drug was significantly greater in Mitchells Plain as compared to arrestees tested at the Phoenix and CR Swart police stations.

By Offense Category

Information on drug status by offense category for the metros combined is given in Table 7. Persons arrested for housebreaking and drug/alcohol offenses in particular were more likely to test positive for any drug (65.9% and 75.0%, respectively), mostly cannabis, Mandrax, and cocaine. Fifty percent or more of persons arrested on charges of rape, motor vehicle theft, and other thefts also tested positive for at least one drug. With regard to property offenses, the proportion of arrestees who were positive for any drug, cannabis, Mandrax, and cocaine was highest in Cape Town. In Cape Town and Durban, 47% (46.8% and 47.3%, respectively) of persons arrested for violent offenses tested positive for drugs. In Cape Town, 81.7% of arrestees arrested for drug or alcohol-related offenses tested positive for at least one drug and in Durban 72.2% of persons arrested for weapons-related offenses tested positive for at least one drug. Over half (58.7%) of women arrested on prostitution-related charges tested positive for drugs, with almost a third (31.4%) testing positive for cocaine.

By Prior Arrest

Over half (50.6%) of arrestees who tested positive for at least one drug acknowledged having had a prior arrest, compared to 29.2% of arrestees who did not test positive for drugs ([X.sup.2] = 47.694, df = 1, p = 0.000).

Self-Report Data

Alcohol

Between 8.0% (in Johannesburg) and 21.4% (in Cape Town) of arrestees indicated that they were in need of alcohol at the time the alleged crime took place, and between 5.9% (in Johannesburg) and 23.0% (in Cape Town) of arrestees reported being under the influence of alcohol at the time the alleged offense took place. In Durban and Cape Town about 10% of arrestees indicated that they used alcohol and/or drugs to commit the alleged offense. Various reasons were given for why they consumed substances prior to committing the alleged offense, including giving them resolve to commit the crime. Just under half (49%) of persons arrested on charges relating to family violence indicated that they were under the influence of alcohol at the time of the alleged offense.

Need for Treatment

Arrestees were also asked whether they felt they could use treatment for the drugs they reported using. A high proportion indicated that they could use treatment, ranging across sites from 16.8% to 29.9% for those who reported alcohol use and 26.6% to 34.1% of those who reported cannabis use. Perceived need for treatment was also high for the use of the harder drugs (such as Mandrax and cocaine); however, self-reported use of these drugs was low. Few arrestees who indicated use of a particular drug indicated that they had ever received any form of treatment for problems associated with that drug. For example, with regard to Mandrax, in Cape Town 8.0% of users indicated that they had previously received treatment for Mandrax-related problems, but 33.2% indicated that they could benefit from treatment for Mandrax-related problems.

DISCUSSION

Over the three South African sites just under half of all arrestees (45.3%) tested positive for at least one of six drugs in the second half of 2000. While exact comparisons with other countries are not easy to undertake due to methodological differences between studies, it appears that the percentage testing positive for any of several drugs (excluding alcohol) in this study is fairly similar to that observed in a pilot study undertaken in one site in Chile in 1999 (47.8%) (14). However, it is somewhat less than was observed in research undertaken England and Wales in 1999-2000 (65%), the United States in 1996 (66.3%), Scotland in 1999 (71.0%), and Australia in 1999 (76.0%) (15-8).

As with studies conducted elsewhere, the drug most likely to be detected among arrestees was cannabis, with between one-quarter and one-half of arrestees testing positive depending on the location. Across sites, Mandrax (methaqualone) was the second most commonly detected drug, with approximately one in five arrestees testing positive for this substance. Less than five percent of arrestees tested positive for any one of the following drugs: cocaine, benzodiazepines, amphetamines, or opiates--substantially less than was reported in research conducted in Australia and England/Wales (15,18). The high percentage of arrestees testing positive for Mandrax in part reflects the unique drug market that has developed in South Africa for this synthetic sedative hypnotic (which is combined with antihistamine), which acts as a central nervous system depressant (19).

Significant differences were found between the three sites in terms of the proportion of arrestees testing positive for any drug as well as for particular drugs. The higher percentage of arrestees testing positive for at least one drug in Cape Town and Durban as compared to Johannesburg is likely to reflect the fact that a substantially higher percentage of persons included in the Johannesburg sample were arrested on charges relating to immigration offenses than in the other sites. Persons arrested on such charges were less likely to test positive for drug use (Table 7). In addition, the Johannesburg sample comprised a higher proportion of African arrestees--the group least likely to test positive for drugs (Table 5). The finding that a higher percentage of arrestees in Cape Town tested positive for Mandrax is likely to reflect differences in drug markets in these cities. The Mandrax trade is firmly rooted in the gang activities in Cape Town (20). The findings of this study further support reports from other studies that indicate that levels of substance use and substance abuse-related problems are in general higher in Cape Town than in other major urban areas in South Africa (21,22).

Due to the government's policy of apartheid (which among other things prescribed where people could live and their employment prospects), a number of ethnically specific market chains for drugs evolved in South Africa. This has tended to influence the kinds of drugs used by different race groups in this country. The relationship between race, drug use, and crime has been highlighted before (5), but should not be understood as if race is a variable that independently defines drug use behavior. In the South African context race is unfortunately inextricably bound to other factors such as socioeconomic status that also must be taken into account. Cannabis appears to be a drug that arrestees reporting lower monthly income are more likely to use, whereas the converse is true for cocaine. In fact, 78% of the white arrestees came from the highest income level group (as measured by legal and illegal income brought in during the past 30 days), with 43% of white arrestees testing positive for cocaine and 10% of persons in the highest income level testing positive for cocaine (compared to 5% overall).

The gender differences reported in this study, that is, higher levels of male arrestees testing positive for cannabis than females but greater proportions of females testing positive for cocaine, opiates, and amphetamines is in line with the findings of the English/Welsh study of 1999-2000 (15). The high percentage of female arrestees testing positive for cocaine, in particular, is likely to reflect the high level of cocaine use among female sex-workers (20). The finding that arrestees aged 20 years and younger were the group having the highest proportion of persons testing positive for at least one drug (mainly cannabis and/or Mandrax) is in line with the high level of drug use among adolescents indicated by other studies conducted in South Africa (21). In addition, the finding that levels of cocaine were highest in the youngest group of arrestees debunks the commonly held view in South Africa that cocaine use among young people is likely to be low due to it being more expensive. The increasing availability of the cheaper variety of cocaine, crack cocaine, is likely to have increased its use among young people.

Persons in the sample arrested for housebreaking and drug/alcohol offenses appear to be more likely to test positive for drugs (mostly cannabis, Mandrax, and cocaine) than persons arrested on other charges. Fifty percent or more of persons arrested on charges of motor vehicle theft and other thefts also tested positive for at least one drug. There is a broad body of research highlighting the link between drug use and property crimes such as housebreaking and theft. This research has mainly focused on drugs such as heroin and to a lesser extent cocaine, and has reinforced the view of crime being committed to obtain cash or goods to purchase drugs for own use (6,7,18). The study also briefly explored arrestees' perceptions of why they took substances. About 10% of arrestees in Cape Town and Durban indicated that they used substances to assist them in committing the crime, principally to enhance courage and reduce nervousness--a position that has been expressed in other studies (3). With regard to the link between drug use and the commission of alcohol and drug offences, Friedman, Glassman, and Terras (23), in a study of young, inner-city, low socioeconomic status African-Americans in the United States, found that both cocaine/crack and cannabis use was related to the frequency of being involved in the selling of drugs. Given that many drug dealers sell drugs in order to support their own habit it is not surprising that a high proportion of persons arrested on alcohol/drug offenses tested positive for drugs.

With regard to violent offenses, almost half of persons arrested on charges of (attempted) murder or rape or on weapons charges tested positive for drugs, and just under half (49.2%) of persons arrested on charges relating to family violence indicated that they were under the influence of alcohol at the time of the alleged offense. While the research was not designed to show a causal relationship between substance use and violent crime, the study does support the growing body of research pointing to a strong association between substance use and violent crime (6,23).

Arrestees who tested positive for at least one drug were significantly more likely to have had a prior arrest as compared to arrestees who did not test positive for drugs. This reinforces the view that drug users place an inordinate burden on the criminal justice system and raises the possibility of reducing this burden through some form of intervention. The gap between arrestees' need for treatment for a range of substances and having received treatment in the past suggests that this is an area for consideration. Internationally, a variety of prevention programs have been designed to break the cycle of drugs and crime as well as the burden placed on the criminal justice system by persons arrested for drug-related crimes. These include community development programs, diversion programs, treatment programs in prison, and treatment programs in general (24-27). A study of clients recruited to the National Treatment Outcome Research Study (NTORS) in the United Kingdom, for example, found a substantial reduction in criminal behavior among drug users following treatment. Specifically, a 1-year follow-up of 753 clients recruited to NTORS demonstrated that the number of crimes was reduced to one third of intake levels and criminal involvement was reduced by about half following addiction treatment (25).

The clearest implications for policy from this study are that strategies to reduce drug use and drug-related crime must be area and even suburb specific. The prevalence of drug use among the youth requires specific attention, particularly from the justice and welfare sectors responsible for diversion and rehabilitation. Specific studies investigating the link between drugs and crime among juvenile arrestees also are required. Given the highly addictive and socially damaging nature of cocaine, efforts need to focus on this drug in high risk areas. Health education programs could also target users in specific police stations.

Training police to recognize particular symptoms and establishing protocols on handling arrestees under the influence will assist the police in making arrests and interviewing and handling arrestees, given that nearly half of the arrestees had recently consumed some drug. Treatment of drug using offenders either as part of a sentence or through referrals by the court also deserves more consideration. Targets should be set to reduce drug positive arrestees through court ordered treatment and other means.

In concluding it is important to indicate that there are several limitations to the study. First, the police stations selected were not representative of all stations in the three cities and they are certainly not representative of all police stations in the country. This limits the extent to which the findings can be generalized more widely. In future it might be useful to adopt a form of proportional representative sample of police stations in the country to arrive at national estimates. This approach is being considered in the U.S. ADAM study. Second, as has been pointed out by Makkai (18), offenders who are detained by the police are only a subset of the total population of offenders--those who commit crimes that lead to an arrest or those persons who are not able to evade arrest. Studying only arrestees therefore may misinterpret the true nature of the relationship between drugs and crime (28). Third, the design of the study does not permit the attribution of a causal relationship between drug use and crime. It is highly likely that the relationship is bidirectional, with drug use playing a role in the commission of crimes and with crime reinforcing drug-using behavior. The study in fact highlights the need to investigate further the link between drug use and committing crime. This may well require the use of other kinds of research methods, e.g., qualitative methods (focus group interviews, key informant interviews, and even anthropological studies). Finally, no confirmatory tests were undertaken to determine specific types of opiates, amphetamines, and benzodiazepines. This weakened the study's ability to identify, for example, whether an opiate positive arrestee had consumed heroin, morphine, or codeine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research on which this paper is based was supported by a grant from the South African Department of Arts, Culture, Science & Technology's Innovation Fund (Crime Prevention Towards Improved Information and Intelligence). We acknowledge the support of Aki Stavrou and staff at DRA Development in the collection of the data, Dr. Peter Smith and staff at the Department of Pharmacology at the University of Cape Town for the analysis of the urine samples, and Dr. Chris de Kock and colleagues of the South African Police Service's Crime Information Analysis Centre for assisting with the execution of the project. We also acknowledge the technical support provided by Drs. Jack Riley and Bruce Taylor at the U.S. National Institute of Justice and Dr. Phyllis Newton of ABT Associates.

REFERENCES

(1.) Schonteich M, Louw A. Crime in South Africa: a Country and Cities Profile. ISS Paper. Vol. 49. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2001.

(2.) Crime Information Analysis Centre. The Reported Serious Crime Situation in South Africa for the Period January-September 2001. Pretoria: South African Police Crime Information Analysis Centre, 2001:1-16.

(3.) Brunelle N, Brochu S, Cousineau M.-M. Drug--crime relations among drug-consuming juvenile delinquents: a tripartite model and more. Contemp. Drug Probl. 2000; 27:835-866.

(4.) Foster J. Social exclusion, crime and drugs. Drugs Educ Prev Policy 2000; 7(4):317-330.

(5.) French MT, McGeary KA, Chitwood DD, McCoy CB, Inciardi JA, McBride D. Chronic drug use and crime. Subst Abuse 2000; 21(2):95-109.

(6.) Sinha R, Easton C. Substance abuse and criminality. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1999; 27(4):513-526.

(7.) Stewart D, Gossop M, Marsden J, Rolfe A. Drug misuse and acquisitive crime among clients recruited to the National Treatment Outcome Research Study (NTORS). Crim Behav Ment Health 2000; 10:10-20.

(8.) Taylor BG, Fitzgerald N, Hunt D, Reardon JA, Brownstein HH. ADAM Preliminary 2000 Findings on Drug Use and Drug Markets--Adult Male Arrestees, NCJ 189101. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, 2001:1-57.

(9.) Thomson LDG. Substance abuse and criminality. Curr Opin Psychiatry 1999; 12:653-657.

(10.) Burrows S, Bowman B, Matzopoulos R, Van Niekerk A. A Profile of Fatal Injuries in South Africa 2000: Second Annual Report of the National Injury Mortality Surveillance System. Cape Town: Medical Research Council, 2001:1-31.

(11.) Peden M, Van der Spuy J, Smith P, Bautz P. Substance abuse and trauma in Cape Town. S Afr Med J 2000; 90(3):251-255.

(12.) Rocha-Silva L, Stahmer I. Nature, Extent and Development of Alcohol/ Drug-Related Crime. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council, 1996:1-240.

(13.) Wolff K, Farrell M, Marsden J, Monteiro MG, Ali R, Welch S, Strang J. A review of biological indicators of illicit drug use, practical considerations and clinical usefulness. Addiction 1999; 94(9):1279-1298.

(14.) Caris L, Taylor B. Chile. In: Taylor B, ed. I-ADAM in Eight Countries: Approaches and Challenges. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, 2002:29-46.

(15.) Bennett T, Holloway K, Williams T. Drug Use and Offending: Summary Results from the First Year of the NEW-ADAM Research Programme. Vol. 148. London: UK Home Office, 2001, 1-4.

(16.) Taylor B, Bennett T. Comparing Drug Use Rates of Detained Arrestees in the United States and England. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, 1999:1-60.

(17.) McKeganey N, Connelly C, Narrie J, Knepil J. Scotland. In: Taylor B, ed. I-ADAM in Eight Countries: Approaches and Challenges. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, 2002:97-116.

(18.) Makkai T. Patterns of recent drug use among a sample of Australian detainees. Addiction 2001; 96(12):1799-1808.

(19.) Bhana A, Parry CDH, Myers B, Pluddemann A, Morojele NK, Flisher AJ. The South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU) project, phases 1-8-cannabis and Mandrax. S Afr Med J 2002; 92(7):542-547.

(20.) Leggett T. Rainbow Vice: The Drugs and Sex Industries in the New South Africa. New York: Zed Books, 2001.

(21.) Parry CDH, Bhana A, Pluddemann A, Myers B, Siegfried N, Morojele NK, Flisher A J, Kozel N. The South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU) description, findings (1997-1999) and policy implications. Addiction 2002; 97(8):969-976.

(22.) Parry CDH, Bhana A, Myers B, Pluddemann A, Flisher A J, Peden MM, Morojele NK. Alcohol use in South Africa: findings from the South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU) project. J Stud Alcohol 2002; 63(4):430-435.

(23.) Friedman AS, Glassman K, Terras A. Violent behavior as related to use of marijuana and other drugs. J Addict Dis 2001; 20(1):49-72.

(24.) Dorn N, Seddon T. Welfare, partnership and crime reduction: aspects of court referral schemes for drug users. Drugs Educ Prev Policy 1996; 3(1):57-70.

(25.) Gossop M, Marsden J, Stewart D, Rolfe A. Reductions in acquisitive crime and drug use after treatment of addiction problems: 1-year follow-up outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend 2000; 58:165-172.

(26.) Jones J. Drug treatment beats prison for cutting crime and addiction rates. BMJ 1999; 319(7208):470.

(27.) Lo C, Stephens R. Drugs and prisoners: treatment needs on entering prison. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2000; 26(2):229-245.

(28.) McClelland GM, Teplin LA. Alcohol intoxication and violent crime: implications for public health policy. Am J Addict 2001; 10(Suppl.):70-85.

Charles D.H. Parry, M.Sc., M.A., Ph.D., (1), * Andreas Pluddemann, M.A., (1) Antoinette Louw, M.A., (2) and Ted Leggett, M.Soc.Sci., J.D. (2)

(1) Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research Group, Medical Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa

(2) Crime and Justice Programme, Institute for Security Studies, Pretoria, South Africa

* Correspondence: Charles D.H. Parry, M.Sc., M.A., Ph.D., Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research Group, Medical Research Council, P.O. Box 19070, Tygerberg (Cape Town), 7505, South Africa.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Taylor & Francis Ltd.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group