Bacterial Vaginosis

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the most common cause of vaginal complaints and abnormal vaginal discharge and odor. BV consists of a significant polymicrobial overgrowth in which the bacteria act synergistically to cause an odor and discharge, and may lead to potential complications in the uterus and fallopian tubes. It is best to consider BV to be the result of alterations in the vaginal ecosystem, rather than an infection caused by any single miroorganism. In BV, the environment of the vagina shifts from a predominance of lactobacilli to a predominance of anaerobes (mainly Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus species, Eubacterium species, and Mobiluncus) and facultative bacteria (Mycoplasma species, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Streptococcus species and Gardnerella vaginalis). This overgrowth results in the degradation of the mucus membrane and shedding of the vaginal epithelium, resulting in a discharge. The destruction of these mucins exposes the epithelium to other organisms, with the subsequent appearance of clue cells. (1)

BV is characterized by decreased or absent Lactobacillus species and increased concentrations of potentially pathogenic bacteria. Other characteristic changes include elevated pH, > 4.5, formation of clue cells, odor due to increased vaginal fluid concentrations of diamines, polyamines and organic acids, (2-4) an upregulation of inflammatory cytokines such as Interleukin (IL)-1beta, a noticeable absence or rare presence of white blood cells in the vaginal discharge, and a decrease in naturally protective molecules like secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor.

In most women, the vagina becomes inhabited by Lactobacillus species at the time of menarche. The Lactobacilli produce hydrogen peroxide, which inhibits the growth of pathogenic organisms. There are three main factors that are responsible for the downward shift of (lactobacilli), the consequential increase in other bacteria and the development of BV: 1) intercourse (without a condom) alkalinizes the vagina which depletes Lactobacilli; 2) douching--which also depletes Lactobacilli; 3) and the absence of peroxide-producing Lactobacilli in the vagina. An additional possibility for some women is that the lactobacilli were eliminated through the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. (5)

More than 50% of women with BV are asymptomatic. BV most often occurs among heterosexual, sexually active women. Among those who are heterosexually active, BV is more frequent in women who have had intercourse at an early age, those with more sexual partners, and among women with concurrent or prior sexually transmitted diseases. (6) BV can also exist among sexually abused children and lesbian partners of women with bacterial vaginosis. (7,8) The fact that BV is evident in virgin women and children confirms the likelihood that it is not exclusively a sexually transmitted disease. In addition, treatment of male partners does not prevent recurrence of BV in their female partners. (9,10)

Bacterial vaginosis may be merely an acute or episodic condition, may become persistent, or may resolve spontaneously. Several factors have been associated with the development of BV, such as cigarette smoking. This may be due to the possible down-regulation of the immune system response or the association of smoking with other behaviors that are risk factors for BV. Racial background has also been associated with the development of BV. Hispanic women are 50% more likely than Caucasian women to develop BV and African American women are twice as likely to have BV. (11) The reasons for these differences are not clear. It is thought that Hispanic women are less likely to use condoms due to partner requests, and African American women, who practice douching twice as often as Caucasian women, are less likely to have lactobacilli in the vagina.

Consequences of altered vaginal flora include other concerns than just BV. The alterations in vaginal immune response and vaginal microflora, leave women more susceptible to other infections, including HIV and gonorrhea. (12-15) Women with BV are also more likely to shed HIV, and therefore may increase the transmission of HIV. (16)

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is also associated with BV. The loss of Lactobacilli and the resulting degradation of the mucin layer, as well as loss of the local immune response, may allow pathogens to ascend to the uterus and fallopian tubes. BV is also linked to preterm birth and is associated with postpartum endometritis. Additionally, women with suboptimal vaginal flora are at increased risk for infections following gynecologic surgery.

It has been estimated that about 30% of women experience a recurrence of symptomatic BV within 30 to 90 days of treatment, and 70% will have a recurrence within 9 months. (17) With BV, it may not be clear whether the repeat episode is a re-infection or a relapse. With BV, reinfection implies that the original problem has been reversed and the patient is now completely asymptomatic, the vaginal pH is now normal, and the vaginal flora is now lactobacillus-dominant. Relapse indicates that the symptoms and microbiology have never returned to normal even though there may be improvement or a period of improvement. Reinfection is a possibility, for example, exposure to the same set of contributing factors related to the first episode--the same male partner who is not using a condom. Although it is not convincing that BV is a sexually transmitted disease, we do know that the semen is alkaline and alters significantly the pH of the vagina. For most women, the issue is not re-infection but relapse and the focus in recurrent BV should be more on relapse. Possible mechanisms include: 1) lack of reestablishing the Lactobacillus-dominant vaginal flora, 2) persistent overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria, and 3) some of the pathogens have sequestered themselves in inaccessible sites such as the endometrial cavity.

A simple and useful in-office method for monitoring patients during treatment for BV is pH paper. If a woman has a vaginal pH of less than 4.5, (some say < 5.0) she has adequate numbers of lactobacilli, and does not have BV.

The goal of treatment is to restore the vaginal pH to < 4.5 and to reestablish normal ecology by having dominance of Lactobacillus species. Treatment strategies for BV should be demonstrated by resolution of clue cells and amine odor, and restoration of a lactobacilli dominant vaginal flora. A fundamental part of management is to reexamine the patient following the initial treatment to assure that her pH has decreased to < 4.5. If it has not, then she is at risk for developing a recurrence or having a vaginal microflora that is dominated by facultative anaerobic bacteria, i.e. BV. In those individuals where the pH remains > 4.5 following treatment, more aggressive use of lactobacillus and/or vaginal boric acid suppositories should be utilized. The first followup should occur after the designated treatment time of usually 7-14 days; then again in 1 month to determine the result has been sustained. Patients who relapse should be treated with boric acid and lactobacillus vaginally for 1-2 weeks, plus lactobacillus orally for 2-6 months. Just repeating antimicrobial treatments may further alter vaginal ecology unfavorably.

Women should refrain from sexual intercourse during the treatment period and until they have been reevaluated and found to have a normal vaginal ecology. For those women who do have recurrent BV following intercourse, they may need to use condoms, or consider having the sexual partner treated at the same time. The best treatment for BV is one that will lead to resolution of symptoms and offers the most likelihood for restoring the lactobacilli ecosystem.

Natural Medicine Treatment options

Lactobacillus suppositories -- "CandaClear" (available from Pharmax)

Oral lactobacillus -- "HLC hi potency" or "HLC maintenance" (available from Pharmax)

"Herbal-C" suppositories -- contains Myrrh, Echinacea, Slippery elm, goldenseal root, marshmallow, Geranium and yarrow (available from Vitanica)

"Vag-Pak" suppositories -- contains Anhydrous magnesium sulfate, Glycerin complex, Hydrastis tincture, Thuja oil, Tea tree oil, Bitter orange oil, Vitamin-A (as palmitate) 100,000 iu, Ferric sulfate, Ferrous sulfate in polybase. (available from Vitanica)

"Yeast Arrest" (boric acid suppositories 600 mg) -- contains boric acid, calendula, Oregon grape root. (available from Vitanica)

Sample Treatment Plan

1. "Herbal-C" suppositories -- insert five days per week for 2 weeks

2. "Vag-Pak" suppositories -- insert one 2 days per week for the same 2 weeks as "Herbal-C"

3. Follow with "CandaClear" suppository -- insert daily for 6 days

4. Oral lactoabillus "HLC maintenance" -- take one daily for 2-6 months to restore normal vaginal ecology

5. If recurrence--add Yeast Arrest suppositories -- insert one daily for 2 weeks

Conventional Treatment Options

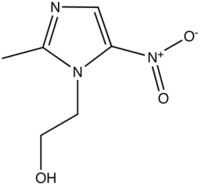

Metronidazole 250 mg 3x/day orally for 7 days; or

Metroniddazle 2 g as a single oral dose; or

Metronidazole gel 0.75% (MetroGel-Vaginal, 3M) intravaginally once a day for 5 days.

Clindamycin 2% intravaginally once a day for 7 days; or

Clindamycin ovules (Cleocin, Pfizer) once a day for 3 days

Atrophic Vaginitis

Normal estrogen levels are a necessity for healthy vaginal tissue and adequate vaginal blood flow, lubrication, and sensitivity. As such, low-estrogen states like pre-pubescence, postpartum, lactation, and peri- and postmenopause lead to atrophic changes that cause a plethora of symptoms that lead women to consult their physicians. Atrophic vaginal symptoms occur in as many as 15% of premenopausal and 10-40% of postmenopausal women. Even 10-25% of those taking hormone replacement therapy complain of symptoms associated with atrophic changes. Symptoms may mimic a vaginal infection and include burning, pressure, itching, soreness, dryness, a clear, thin and/or bloody malodorous discharge, a smoothening of vaginal walls, decreased vaginal tone, and pain with intercourse or lack of sexual arousal due to a thinning and subsequent tearing of vaginal tissue. As such, many women suffering from atrophic vaginitis often receive incorrect diagnoses and, therefore, inappropriate treatment for months to years before the true cause is identified.

Estrogen and other factors help to keep the vaginal tissue healthy and pH low. This acidic environment discourages growth of pathogenic bacteria. In atrophic vaginitis, there is an increase in pH (between 5-7) and a corresponding decrease in acidity and, as a result, pathogenic bacteria flourish while protective lactobacilli decrease. This scenario predisposes one to vaginal infection in the already atrophic environment, thereby worsening symptoms. Additionally, the low-estrogen environment leads to atrophy of the urethra and bladder and a subsequent increased susceptibility to urinary tract pain, frequency, incontinence, and infection.

Other factors predisposing to atrophic changes include chemo- and radiation therapy, cigarette smoking, lack of sexual activity, nulliparity, and anti-estrogen medications like Tamoxifen, Provera, and Lupron. Exogenous agents such as perfumes, powders, soaps, deodorants, panty liners, spermicides and lubricants may contain irritant compounds that worsen symptoms. In addition, tight-fitting clothing and long-term use of sanitary pads or synthetic materials can further irritate tissue.

Since the main cause of atrophic vaginitis is low estrogen, estrogen replacement, orally and/or topically, usually leads to complete symptom resolution in a matter of weeks. Estrogens can restore vaginal architecture, pH, flora, fluid secretions, mucosa thickness, blood flow, and sensitivity thereby providing symptomatic relief. Oral estrogens have the additional benefits of relieving other menopause symptoms, such as hot flushes and mood changes. However, even women who have menopausal symptoms under control with oral estrogens often continue to suffer from vaginal atrophy and, therefore, may benefit from an intravaginal preparation as well. Women with no or tolerable menopausal symptoms or those who have contraindications to systemic hormone replacement therapy should preferentially use intravaginal therapy alone. Intravaginal treatment is very low-dose, has minimal systemic absorption and, therefore, is not customary to oppose with progesterone or progestins if used in a maintenance dose of not more than twice weekly. There are a number of forms available including ring, suppository, tablets and creams. Research suggests that synthetic estrogen creams tend to carry a higher risk of side effects such as uterine bleeding, breast pain, perineal pain and endometrial over-proliferation in women who use a cream vs. other topical methods. Compounded products are free from the potentially irritating additives found in many commercial products and, therefore, may be preferable. Vaginal estriol in particular has added appeal due to the high amount of estriol receptors in the vagina. Topical moisturizers and lubricants (Replens, vitamin E) can also be used while the tissue is healing.

Indications: vulvar and vaginal atrophy (Premarin and Vagifem are indicated for atrophic vaginitis; Femring is also indicated for moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms)

Though continued use has not been studied in long-term randomized controlled trials, most practitioners feel comfortable using these products, preferable in natural forms at the lowest possible dose, indefinitely, to maintain tissue integrity and to control symptoms. In addition, atrophic changes will return within four weeks after discontinuing estrogen therapy so continued use is often necessary

Adverse Effects

Common: headache, nausea, vaginal discomfort, vaginal candidiasis

Rare: vaginal trauma from the applicator if patient has severe atrophy

Dosing and administration: Daily dosing will achieve systemic concentrations; low dose, 1-3/weeks will achieve predominantly local effects

Drug interactions: See oral estrogens (except antibiotics and nicotine); interactions are based on extent of systemic absorption.

Atrophic Vaginitis References

www.fpnotebook.com

www.gpnotebook.co.uk

www.cochrane.org/cochrane/revabstr/AB001500.htm.

Bachmann, GA, Nevadunsky, NS. Diagnosis and Treatment of Atrophic Vaginitis Am Fam Phys. 61(10), 2000

Bates, B. OB/Gyn News 37(13): 18, 2002

Willhite, LA. Urogenital Atrophy: Prevention and Treatment.

Pharmacotherapy. 21(4):464-480, 2001.

Conflict of interest statement: Dr. Hudson is the director of research, development and education for VITANICA

References

1. Olmsted S, Meyn L, Hillier S. Production of mucin degrading enzymes by vaginal bacteria. Abstr. Ann Meeting. International Congress of Sexually Transmitted Infections. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2001;12 (Suppl 2): 68-69.

2. Amsel R, Totten P, Spiegel C, et al: Nonspecific vaginitis: Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med 1983;74:14.

3. Hillier S, Holmes K: Bacterial vaginosis. In: Holmes K, Mardh P-A, Sparling P, et al (Eds): Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 2nd ed. New York, McGraw-Hill Information Services Co. 1990, pp 547-559.

4. Pybus V, Onderdonk A: Evidence for a commensal, symbiotic relationship between Gardnerella vaginalis and Prevotella bivia involving ammonia: Potential significance for bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis 1997;175:406.

5. Vallor A, Antonio M, Hawes S, Hillier S. Factors associated with acquisition of, or persistent colonization by, vaginal lactobacilli: role of hydrogen peroxide production. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1431-1436.

6. Barbone F, Austin H, Louv W, Alexander W: A follow-up study of methods of contraception, sexual activity, and rates of trichomoniasis, candidiasis and bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;75:1028

7. Hammerschlag M, Cummings M, Doraiswamy B, et al: Nonspecific vaginitis following sexual abuse in children. Pediatrics 1985;75:1028.

8. Berger B, Kolton S, Zenilman J, et al: Bacterial vaginosis in lesbians: A sexually transmitted disease. Clin Infect Dis 1995;21:1402.

9. Vejtorp M, Bollerup A, Vejtorp L, et al: Bacterial vaginosis: A double-blind randomized trial of the effect of treatment of the sexual partner. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1988;95:920.

10. Vutyavanich T, Pongsuthirak P, Vannareumol P, et al: A randomized double-blind trial of tinidazole treatment of the sexual partners of females with bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol 1993;82:550.

11. Goldenberg R, Klebanoff M, Nugent R, Krohn M, Hillier S, Andrews W. Bacterial colonization of the vagina during pregnancy in four ethnic groups. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1618-1624.

12. Martin J, Richardson B, Nyange P, et al. Vaginal lactobacilli, microbial flora, and risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexually transmitted disease acquisition. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1863-1868.

13. Taha T, Hoover D, Dallabetta G, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and disturbances of vaginal flora: association with an increased acquisition of HIV. AIDS. 1998;12:1699-1706.

14. Hillier S. The vaginal microbial ecosystem and rrsistance to HIV. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14 (Suppl 1): S17-S21.

15. Cohen C, Duerr A, Pruithithada N, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and HIV seroprevalence among female commercial sex workers in Chiang Mi, Thailand. AIDS. 1995;9:1093-1097.

16. Cu-Uvin S, Hogan J, Caliendo A, Harwell J, Mayer K, Carpenter C. Association between bacterial vaginosis and expression of human immunodeficiency virus type! RNA in the female genital tract. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:894-896.

17. Blackwell A, Fox A, Phillips I, Barlow D. Anaerobic vaginosis (nonspecific vaginitis): clinical, microbiological, and therapeutic findings. Lancet. 1983;2:1279-1382.

by Tori Hudson, ND & Leigh Kochan, ND, LAc

Dr. Hudson is Professor, NCNM; clinical professor, Bastyr U/SCNM; Medical Director, A Woman's Time; and Dr. Kochan is second year resident, National College of Naturopathic Medicine

2067 N.W. Lovejoy * Portland, Oregon 97209 USA

503-222-2322 * womanstime@aol.com

COPYRIGHT 2005 The Townsend Letter Group

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group