When a groggy reporter complaining of difficulties falling asleep recently visited a doctor in Washington, D.C., the physician's quick solution was to offer her a free sample of a drug called Rozerem (ramelteon). "What do you know about the drug?" the reporter queried, as reporters are apt to do. Noting that the medicine had been approved only a few months earlier, the doctor confessed to knowing next to nothing about it. Since 2000, prescriptions for sleeping pills have increased in all age groups, nearly doubling for children and young adults. Last year, doctors across the country doled out millions of scripts for Ambien (zolpidem) and its relatives in the group known as hypnotic drugs. Doctors also prescribed unofficial sleep aids, including antidepressants and anti-epileptic drugs, to slumber-deprived patients.

The options are still increasing. In the past year, several new drugs targeting insomnia reached the market. One was a variation on an older medication; others took advantage of new insights into sleep biology. In addition to the novel drug Rozerem (ramelteon), the Food and Drug Administration approved the hypnotic drugs Lunesta (eszopiclone) and a new, slow-release formulation of zolpidem called Ambien CR. At least one other hypnotic compound, indiplon, could appear in pharmacies next year. A few novel anti-insomnia drugs are currently being tested.

Whether new or old, few of the prescription drugs used to treat insomnia have been tested in sleep trials that lasted longer than 6 weeks. Yet many patients take them nightly for months or even years at a stretch.

A report by a panel of sleep specialists put together by the National Institutes of Health concludes: "Even for those treatments that have been systematically evaluated, the panel is concerned about the mismatch between the potential lifelong nature of this illness and the longest clinical trials, which have lasted 1 year or less." The report (see box page 345) was published in the September Sleep.

For some of the experimental drugs, 6-month and 1-year trials have started. Still, treating insomnia remains an exercise of educated guesswork.

The sleep-deprived reporter chose a conservative route. She left her doctor's office with a 60-day prescription for Ambien, which was approved in 1992 and has stood the test of time.

SLEEPLESS EVERYWHERE Nearly a third of the U.S. population experiences disrupted sleep, which can include problems falling asleep, inability to stay asleep, and failure to feel restored by sleep. Sleep in 10 percent of the population is so dysfunctional that it impairs daytime performance and therefore qualifies as insomnia. For most of these people, insomnia occurs night after night for months or years.

"Only about 5 percent of patients with insomnia actually go in to see their doctors about it," says psychologist Sonia Ancoli-Israel of the University of California, San Diego. 'About 24 percent will mention it when they happen to be at their doctor's office for something else," says Ancoli-Israel, who is director of sleep medicine for the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System.

The insomniacs who are diagnosed are increasingly turning to prescription sleep aids, according to an analysis released on Oct. 17 by the prescription-management firm Medco Health Solutions of Franklin Lakes, N.J.

Data analysts at the firm reviewed prescription drug claims made by 2.4 million U.S. consumers through pharmaceutical-benefits plans that Medeo oversees. Between 2000 and 2004, use of prescription insomnia drugs climbed by 16 percent among people 65 years and older. That age group suffers more insomnia and already uses more medications than any other group does.

Moreover, the popularity of these drugs soared in younger groups, including teenagers.

The most common prescription for insomnia is, in fact, not labeled as a sleeping drug. It's the antidepressant trazodone, which assumed the mantle of a sleeping pill in the early 1990s, after safety concerns had arisen about the previously best-selling drug for insomnia.

Trazodone "became the number-one treatment for insomnia in the United States, even though it had not been studied in a trial until 1998," says psychiatrist Andrew D. Krystal of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C. That single, 2-week study was published in Human Psychopharmacology by a team led by James K. Walsh of St. John's/St. Luke's Hospitals in Chesterfield, Mo. The study supported trazodone's efficacy as a sleep aid.

The earlier sleep medication was triazolam, sold as Halcion. It lost best-seller status when researchers realized that at excessive doses, it could cause memory deficits and hallucinations.

Today, triazolam and other drugs in the same class, all known as benzodiazepines, are still used occasionally as sleep medications, but their popularity has waned significantly, Krystal says. They sometimes cause daytime sleepiness, cognitive impairment, and poor coordination, and they can be addictive.

Furthermore, no benzodiazepine has been studied in an extended, rigorous trial, says Krystal. In fact, the Food and Drug Administration requires labels to specify that such insomnia drugs are for only short-term treatment.

THE AMBIEN AGE Ambien, which dominates the insomnia market, and a few other drugs currently prescribed or awaiting FDA approval mimic benzodiazepines.

Both the benzodiazepines and their mimics bind to and alter a cell-surface structure known as the GABA receptor, to which gamma-amino-butyric acid, or GABA, binds. That neurotransmitter inhibits brain cells from firing, so by enhancing GABXs action, benzodiazepines and their mimics counteract a state of hyperarousal that may contribute to insomnia.

Ambien was the first benzodiazepine-mimicking drug--followed by Sonata (zaleplon) and Lunesta, with another called indiplon, currently being considered for FDA approval.

Because the benzodiazepine mimics are metabolized more rapidly than most benzodiazepines and appear to selectively target GABA receptors in the brain's sleep-wake areas, the newer compounds could cause fewer side effects, says Krystal.

In the 1998 test by Walsh and his colleagues, Ambien proved slightly more effective than trazodone. Neither caused more side effects than the placebo. This trial was funded by the company that marketed Ambien. In the early 1990s, studies in Europe showed Ambien to work for up to a year.

More recently, Walsh, Krystal, Roth, and several colleagues put Lunesta to a prolonged trial. In it, every evening for 6 months, nearly 600 adults with chronic insomnia took a dose of the drug.

Compared with almost 200 similar patients who received a nightly placebo, volunteers getting Lunesta fell asleep 16 minutes sooner, awoke less often during the night, and slept for more hours throughout the study. These individuals also gave higher ratings of their daytime alertness and function and their sense of physical well-being than did those in the placebo group, the team reported in 2003.

Subsequent data from the same volunteers, albeit without the control group, suggested that Lunesta works for at least a year. This follow-up study is slated to appear in Sleep Medicine.

In 2004, Lunesta became the first agent to receive FDA approval for treatment of insomnia without restricting the drug to short-term use, notes Krystal. "It has the best-mapped safety profile in terms of longer use," says Krystal, who has been a consultant to Lunesta's manufacturer, Sepracor, as well as to the makers of several competing drugs.

Recent trials have produced some long-term data for two other benzodiazepine-mimicking drugs. In the March Sleep Medicine, Ancoli-Israel and her colleagues reported that, among 260 elderly volunteers, Sonata initiated sleep improvements that lasted for a full year of treatment.

The average that time it took for the Sonata users to fall asleep dropped during the trial from 80 to 42 minutes.

The study had no control group. However, in the week immediately after the end of the 1-year trial, patients' sleep patterns deteriorated, rising abruptly to 52 minutes. Total sleeping time--which had climbed from 5 hours before treatment to nearly 6 hours during the trial--slipped downward by 6 minutes.

However, a quarter of the volunteers experienced headaches that may or may not have been related to the treatment. In 2 to 5 percent of patients, pain, daytime sleepiness or dizziness, or gastrointestinal distress led to discontinuation of treatment.

Each of the six researchers who reported the trial was either a scientific advisor to Sonata's maker, King Pharmaceuticals of Bristol, Tenn., or an employee of King's commercial partner Wyeth.

Psychologist Martin B. Scharf of the Tristate Sleep Disorders Center in Cincinnati and his colleagues have investigated another benzodiazepine mimic, the experimental drug indiplon. In a recent study, they divided 702 volunteers into groups and gave indiplon or a placebo to each patient for 3 months.

By the end of the trial, indiplon-treated volunteers took about half an hour to fall asleep each night, on average--at least 10 minutes less than those in the placebo group did. The researchers, who were supported by indiplon's joint developers, Neuroerine Biosciences of San Diego and Pfizer of NewYork City, announced their findings in May at the meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in Atlanta.

COUNTING SHEEP To offer yet more sleep enhancers, drug companies are looking beyond benzodiazepine mimics. So far, the promising agents have received only short-term testing.

Merck and the Danish pharmaceutical company Lundbeck, for example, have teamed up to work on a drug called gaboxadol. It targets GABA receptors but doesn't mimic benzodiazepines.

During 6 nights of testing in 26 adults, the drug increased total time asleep by about 11 minutes per night, Roth and his colleagues reported in June at the Denver meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. It also increased average time spent in slow-wave sleep, which some researchers consider particularly restorative, by 20 minutes per night, or 21 percent.

With their eyes on regulatory approval, Merck and Lundbeek now have trials under way in Canada and Europe that will test the drug in more than 600 volunteers for as long as 12 months.

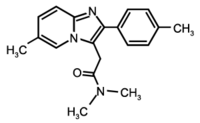

Other insomnia drugs with novel ways of working are in development, but only Rozerem has been approved. It mimics melatonin, a hormone that influences people's daily rhythms. Rozerem latches on to two kinds of melatonin receptors that are located in the brain's suprachiasmatic nuclei, which regulate the sleep-wake cycle.

Some people with sleep difficulties take supplements of melatonin, says Louis J. Mini of Lincolnshire, Ill.-based Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, which makes Rozerem. But "there's never been any evidence that it's effective in treating insomnia," he says.

In a recent trial of Rozerem, 375 adults each spent one night in a sleep laboratory. Volunteers who got the drug fell asleep in 10 minutes less time and slept between 10 and 15 minutes longer, on average, than did those who received a placebo, Roth and his colleagues reported in the March 1 Sleep. Takeda Pharmaceuticals provided financial support for that research.

Several other studies, none of them yet published, confirm Rozerem's sleep-promoting efficacy in adult and elderly patients with chronic insomnia, says Mini. The longest of these trials lasted 5 weeks. Whether the drug will work for longer periods is uncertain.

That's one of the many uncertainties that remain about this and other sleeping pills. Just ask your doctor.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Science Service, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group