Provenge for Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers. Each year in the US, around 230,000 men are newly diagnosed with prostate cancer and 30,000 die of the disease. A new form of immune therapy has shown a significant survival benefit in men who have metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer, when compared to patients receiving placebo.

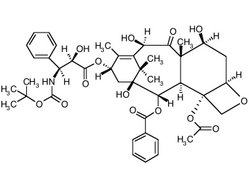

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

The treatment is called Provenge (APC8015) and is manufactured by Dendreon Corp. of Seattle. Provenge is called a vaccine, but unlike most vaccines, it is used not to prevent illness but to treat an already existing condition. The vaccine combines a protein that is found in most prostate cancer cells with a substance that helps the immune system recognize the cancer as a threat. In clinical trials, Provenge was well tolerated: the most common adverse events that were reported were fever and chills lasting for one to two days.

The vaccine is autologous in nature. That is, it is produced from the patient's own cells and must be custom-made for each patient individually. First, patients have their blood run through a machine for two or three hours in order to extract certain immune system cells, called antigen presenting cells (APCs). These cells are then mixed with a protein called prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) that is commonly found on most prostate tumors. The PAP is fused with another immune-stimulating substance called GM-CSF. The mixture is then returned to the patient in a one-hour infusion. This process is repeated three times over the course of a month. The basic idea is to alert the immune system that cells containing prostatic acid phosphatase, (i.e., prostate cancer cells) should now be attacked as if they were a foreign invader.

Antigen-presenting cells (APCs), a class of cells that includes dendritic cells and macrophages, are of major importance in immunotherapy. They are distributed throughout the skin, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract. APCs serve two major functions: they capture and process cell-surface markers, or antigens, for presentation to the T class of lymphocytes. And they also produce signals that are required for the proliferation and differentiation of those lymphocytes.

For several years, dendritic cell vaccines have been offered at CAM-oriented clinics in Mexico, the Caribbean and northern Europe, but have not been available in the US outside the strict confines of clinical trials.

In the latest study, men who were treated with Provenge survived on average 26 months, compared to 21.4 months for those who received only a placebo injection. This may not seem like much, but in fact this 4.5-month median survival benefit is said to be the longest ever reported from a Phase III study in advanced prostate cancer. It is better than the roughly 2.5-month benefit that was shown in clinical trials of Taxotere, a drug from Sanofi-Aventis. Taxotere is presently one of only a few approved forms of chemotherapy for patients whose cancer has spread beyond the prostate gland and is no longer responsive to hormonal therapy (the others are estramustine and mitoxantrone).

What is more, at three years, 28 of the 82 men who received Provenge were still alive, compared to only 4 of 45 patients in the placebo group. Provenge is now considered to have a shot at becoming the first anticancer therapy vaccine to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Approval will probably depend on the results of a larger study, currently underway, which should be reported by the end of 2005.

"This is provocative, it is promising. We now need to confirm this with an independent study," said Dr. Philip Kantoff, a Harvard Medical School professor who heads prostate cancer treatment at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. He was not involved in this latest company-supported study.

The authors of the study emphasized the fact that the men who received the vaccine were actually living longer. However, paradoxically, the study did not achieve its primary goal of delaying the progression of the men's disease. This apparent contradiction has caused some controversy. Some critics contend that "time to progression" is the standard measurement of benefit and should have been extended if the vaccine were truly helping men live longer. Dr. Kantoff described his attitude as "skeptical."

But according to Dr. Stephen Small, MD, professor of medicine and urology at the University of California, San Francisco, who led the Phase III study, "Time to progression is interesting, but it isn't the gold standard. The gold standard is survival. We've improved survival.... A therapy that prolongs life yet avoids the side-effects of other therapeutic approaches is clearly attractive to patients and physicians alike." Dr. Small pointed out that the time to progression was not the right measure to use for judging cancer vaccines because cancer can worsen before the immune system starts to fight it. He said that Provenge improved the survival of all patients, not just those who had less aggressive cancers.

"The survival benefit seen with Provenge is the largest ever reported in this patient population with any therapy," said Dr. Small. "This survival benefit, combined with a favorable safety profile, has the potential to provide an important new treatment option for prostate cancer patients."

According to the Seattle Times, "the treatment has numerous skeptics." These include Patrick Walsh, MD, a Johns Hopkins University urologist and a well-known prostate-cancer surgeon, who said the study was too small to allow definitive conclusions. He said it was unknown what other therapies patients may have had during the three-year follow-up period, which may have made a difference.

"The numbers here are just too small to make this a big deal," said Walsh. Dr. Howard West, an oncologist at Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, said the study would be a stronger statement if the survival edge was seen across a larger number of patients. Still, he called the finding "extremely intriguing."

In addition to Provenge, the company has another vaccine in development. This is called APC8024 and targets HER-2/neu positive cancers, including those of the breast, ovaries, colon and lung.

March 2005 California Trip

In March, 2005, I completed a two-week, 2,000 mile automobile trip through the state of California. I began this journey on March 2 in Long Beach, where I gave the Grand Rounds Lecture at the Todd Cancer Institute. This is a division of Memorial Medical Center (LBMMC), the second largest private hospital on the West coast. Now in its 90th year, this 726-bed hospital is nationally recognized for its excellence in health care. I felt honored to present a lunchtime lecture there on the subject of evidence-based complementary cancer therapy to the Center's physicians, nurses and other staff members.

I also had productive meetings with hospital officials, including Robert A. Nagourney, MD, director of the Todd Institute. Dr. Nagourney is also founder of Rational Therapeutics Institute, which is located across the street from LBMCC. He is best known for his chemosensitivity testing of cancer tissue.

I next drove north to Westwood, where I interviewed Kenneth Conklin, MD, PhD, in his office at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) medical center. Dr. Conklin received his doctorate in pharmacology and did his residency in anesthesiology. For the last eight years, he has focused on CAM and today primarily advises cancer patients on how to use dietary interventions and food supplements in conjunction with conventional chemotherapy for a better outcome. He also practices acupuncture.

From West Los Angeles I again headed south to the world's busiest border crossing in San Ysidro, and to Tijuana beyond that frontier. I met with a number of CAM leaders there, including Gar Hildenbrand, clinical epidemiologist at the Issels cancer vaccine program; Donato Perez Garcia III, MD, director of the Insulin Potentiation Therapy (IPT) clinic; Charlotte Gerson, celebrated founder of the Gerson Research Institute; and Antonio "Tony" Jimenez, MD, of the Rapha (Hope4Cancer) Clinic. One morning, I also had breakfast with Frank Cousineau, vice president of the Cancer Control Society, who also happened to be visiting some of the clinics. Frank periodically conducts tours of the clinics for prospective patients.

From Mexico, I drove back up the coast and visited with Ferre Akbarpour, MD, founder of the Orange County Immune Institute in Huntington Beach, California. We held an interesting discussion of her innovative approach to bolstering the immune system during and after cancer treatment. I also had the pleasure of meeting with the patients at this outpatient institution.

CancerGuides

My final stop was the San Francisco Bay Area. For several days, I participated in the annual CancerGuides conference, convened by James Gordon, MD, and the staff of the Center for Mind Body Medicine (CMBM) of Washington, DC. Dr. Gordon is Clinical Professor in the Departments of Psychiatry and Family Medicine at the Georgetown University School of Medicine. He also served as Chairman of the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy.

Over 100 participants came from all over the country to take part in this weeklong event (March 13-19, 2005). CancerGuides is a unique program that trains health professionals and what some call "expert patients" to assist people with cancer who are seeking to integrate CAM into their treatment plan. ("Expert patients" are laypeople who, by necessity, become educated to the level of professionals through struggle with their disease.)

Participating in this excellent and exciting meeting, which is held at the beautiful Claremont Resort and Spa in Berkeley, was like a homecoming for me. During the 1990s, I worked very closely with Dr. Gordon and his staff, first on the Alternative Medicine Program Advisory Council (AMPAC), of which he was the chair, and then on the Cancer Advisory Panel on Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAP-CAM). I was also on the advisory board of the Comprehensive Cancer Care (CCC) meetings, a prior venture of the CMBM. It was therefore a great pleasure to be back in touch with these leaders in the field of integrating conventional and alternative medicine.

I lectured and also served on two "tumor board"-like panels that discussed particular cases. But I also sat in as a participant and learned a great deal from both the faculty and the many attendees. In addition to Prof. Gordon, these included, but were hardly limited to:

Timothy C. Birdsall, ND, vice president for integrative medicine at the Cancer Treatment Centers of America;

Henry Dreher, MA, a well-known New York City author and CancerGuide;

Joel M. Evans, MD, founder of the Center for Women's Health in Darien, Connecticut, and professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine;

Debra L. Kaplan, LMSW, an integrative psychotherapist in Dallas, Texas;

Susan B. Lord, MD, director of nutrition programs at the Center for Mind-Body Medicine, Washington, DC;

Stephen M. Sagar, MD, Associate Professor, Division of Radiation Oncology, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario;

Susan Sencer, MD, Director of Integrative Cancer Care, Minneapolis/St. Paul Children's Hospital and Clinics; and

Garrett Smith, MD, founder and medical director of the Golden Gate Center for Integrative Cancer Care, San Francisco.

Lately, some writers have speculated that truly alternative medicine is dying, having itself become a victim of the success of milder complementary procedures. They believe that there is no room in the "new world order" for radical challenges to pharmacological medicine. However, my visit to California and Mexico convinces me that alternative medicine is indeed alive and well. But, naturally, it is having to adapt to a changing political and economic environment.

Mark Twain once said, "There is something fascinating about science. One gets such wholesale returns of conjecture out of such a trifling investment of fact." Let's face it: this has been true of many alternative treatments as well--long on conjecture, short on evidence. I am happy to report, however, that the new breed of CAM practitioners now realize that radical ideas are not enough. Those who want to change the system must provide rigorous proof of their concepts. Meetings such as CancerGuides provide an important testing ground for the thorough discussion and documentation of daring new ways of looking at cancer. I'm already looking forward to next year's meeting.

Bibliography

CancerGuides: http://www.cmbm.org/trainings/CancerGuides/index.htm

Conklin KA. Dietary antioxidants during cancer chemotherapy: impact on chemotherapeutic effectiveness and development of side effects. Nutr Cancer. 2000;37:1-18.

Marchione, Marilynn. Treatment for prostate cancer offers promise. Vaccine approach seeks to fight tumors. Associated Press, Feb. 17, 2005.

Moss RW. Patient Perspectives: Tijuana Cancer Clinics in the Post-NAFTA Era. Integr Cancer Ther. 2005;4:65-86.

Pollack, Andrew. Prostate cancer vaccine shows promise in a trial. New York Times, Feb. 17, 2005.

by Ralph W. Moss, PhD, Director, The Moss Reports

[c]2005 Ralph W. Moss, PhD. All Rights Reserved

800-980-1234 * www.cancerdecisions.com

COPYRIGHT 2005 The Townsend Letter Group

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group