Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee

Over 50 percent of people will use marijuana sometime in their life. While intoxication lasts two to three hours, the active ingredient in marijuana, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, can accumulate in fatty tissues, including the brain and testes. Adverse effects from marijuana use include decreased coordination, epithelial damage to the lungs, increased risk of infection, cardiovascular effects and cognitive deficits. Unexplained behavior changes, altered social relationships and poor performance at school or work can signify a drug problem. Treatment requires a combination of education, social support, drug monitoring and attention to comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions. (Am Fam Physician 1999;60:2583-93.)

The word "cannabis" is derived from Cannabis sativa, the name of the marijuana (hemp) plant. Cannabis has been valued for thousands of years throughout the world for making rope, thread and clothes, its psychoactive properties and medicinal purposes.1 The recent discovery of endogenous cannabinoids and cannabinoid receptors, the development of cannabinoid agonists and antagonists, and the continued debate over legalization for medicinal purposes has stimulated recent public interest in marijuana.2

Epidemiology

Marijuana use peaked in the 1960s, but it is still the most widely used illicit drug in the United States. The 1992 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse reported that approximately 5 million Americans were using marijuana weekly.3 In addition, 2 to 3 percent of high school students used marijuana daily, and nearly 70 percent had used it in the past month.3 The average age at which a person starts using marijuana is 18 years.3,4 Prevalence rates of marijuana use differ according to age.3 According to the 1991 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (1979 through 1991), an average of 13 to 35 percent of young adults (18 to 25 years of age) used marijuana monthly, while only about 5 percent of persons between 26 and 34 years of age and approximately 2 percent of those 35 years of age or over used marijuana monthly.3

Many persons who use marijuana also use other drugs, particularly alcohol.5 A sequential pattern of drug abuse in adolescents has been described as the "gateway theory."6 According to this theory, drug use usually begins with legal substances, such as alcohol and cigarettes, and is then followed by marijuana, other illicit drugs and, finally, misuse of prescribed medication.6 This basic pattern is less common among persons who use drugs heavily.

In practical terms, this means that about one half of the people in the United States have used marijuana, many are currently using it and some will require treatment for marijuana abuse and dependence.

Pharmacology

Marijuana is made from the dried leaves and flowers of the hemp plant. The potency of marijuana depends on the method of preparation. Ganja is about three times more potent than marijuana, while hashish is five to eight times more potent. Although cannabinoids are usually smoked, they can also be eaten, drunk as tea or, rarely, injected intravenously. The delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content of marijuana is currently higher than that of the marijuana used in past decades. Many adverse effects that were reported from the 1960s through the 1980s may be understated when compared with the effects of current street preparations.

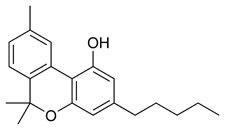

THC, cannabidiol and cannabinol are the most abundant cannabinoids in marijuana. THC is the primary psychoactive component.4,7,8 A metabolite, 11-hydroxy-THC, is also psychoactive.4 THC is metabolized through the cytochrome P450 system. About one third of THC is eliminated through urination and two thirds through fecal excretion.7

Peak plasma levels of THC are normally achieved within 10 minutes of smoking marijuana. Intoxication lasts approximately two to three hours.4 Because of its high lipid solubility, THC accumulates in fatty tissues, leading to its long half-life.4,7,9 When cannabinoids from marijuana used weeks or months ago are detected in a urine drug screen, some people may be unpleasantly surprised, particularly if they are applying for employment, are injured on the job or are involved in a motor vehicle crash.

mechanisms of action

The proposed mechanisms of action of cannabinoids are shown in Table 1.1,4,7,10-14 Marijuana stimulates the dopamine pathway from the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens, which is believed to be a reward system of the brain.

Two endogenous cannabinoid receptors, CB1 (found primarily, but not exclusively, in the brain) and CB2 (found only in peripheral tissues), have been identified.10-12,15 Cannabinoid receptors are most prevalent in the hippocampus, cerebral cortex, basal ganglia and cerebellum, which may account for the primary actions of cannabinoids. Very few cannabinoid receptors are located in the brain stem, which may explain why marijuana used in high dosages does not suppress respiration and why it has a high therapeutic index.

Effects and Reasons for Use

Many people first use marijuana because of curiosity, peer pressure, or both. Use is often continued for the desired effects of euphoria, relaxation, sexual arousal, heightened sensations and socialization with other users.16 Easy access, expectation of few or no legal consequences, attempts at self-medication (for physical and emotional problems) and eventual dependence contribute to chronic use.

adverse effects

Many known physical and behavioral adverse effects accompany the use of marijuana, as shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.1,4,16,17,18-23 In one survey, approximately 40 to 60 percent of persons who use marijuana reported unpleasant side effects.17 Temporal variation occurs in the effects and adverse effects of marijuana. For example, the disruptive effect that marijuana has on coordination may last for more than 24 hours, which is far beyond the period of subjective intoxication.1 Thus, users may be at increased risk for adverse incidents (e.g., motor vehicle crashes, industrial accidents) for longer periods of time than they realize.

Many investigations using animals and some studies of humans suggest that reproductive abnormalities may occur with the use of marijuana (Table 4).1,4,7,13,22,24-26 These effects are less clear in humans. Maternal exposure to marijuana during pregnancy may reduce the size of the fetus and the birth weight.27 A 10-fold increase in the risk of nonlymphoblastic leukemia in children whose mothers used marijuana before or during gestation has been reported.27 Marijuana may also increase the risk of chromosomal damage (including breakage and translocation), but this damage seems to be confined to somatic cells.4,5,7,27

Some patients with pre-existing medical conditions who use marijuana may be at particular risk. For example, although THC acutely increases the respiratory rate and the diameter of bronchial airways, chronic use of marijuana results in epithelial damage to the trachea and major bronchi, and decreased diameter of the bronchial airways.4 Marijuana smoke does not contain nicotine but does have a significantly higher tar content than cigarettes, contains many carcinogens and, unlike most cigarettes, is smoked unfiltered.4,27

A serious adverse effect of marijuana that is often neglected is the risk of infection. For example, chronic use of marijuana may lead to impairment of pulmonary defenses against infection. Marijuana can be contaminated with microorganisms such as Aspergillus and Salmonella, as well as fecal matter. The risk of infection may be of particular concern in patients who have acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.9

The adverse effects of marijuana are of particular concern in older patients and in those with coronary artery disease, hypertension and cerebrovascular disease. For example, marijuana can increase heart rate (a dose-dependent tachycardia), increases cardiac output by as much as 30 percent, alters blood pressure, increases myocardial demand, decreases myocardial oxygen and increases angina.4,7,12,18

Long-term use of marijuana may lead to subtle cognitive deficits. In studies using animals, chronic exposure to marijuana changed the structure and function of the hippocampus in ways similar to the effects of the aging process.27 Acute exposure to marijuana leads to deficits in short-term memory, but long-term effects on cognition are not as well documented.

An "amotivational syndrome" caused by marijuana use is still controversial but of concern. High school students who use marijuana often spend less time on homework, have lower grades and more delinquency.28 Also, college women who use marijuana report significantly higher rates of motor vehicle crashes, smoking, use of alcohol and tranquilizers, use of sex as a coping mechanism, violent dreams, sleeplessness and psychiatric problems than do nonusers.29 "Cause and effect" is still the area of uncertainty, as drug abuse and conduct problems are intimately intertwined, and temporal relationships are often uncertain.

Marijuana use can lead to abuse, tolerance and dependence. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (DSM-IV) does not contain a diagnosis of "cannabis withdrawal"; however, some studies suggest that withdrawal symptoms can develop (Table 5).1,22,25 If present, these symptoms are generally mild, presumably because of the long half-life of marijuana.1

Potential Medical Uses

Marijuana use for medicinal purposes is currently being debated on a national level.30 This topic extends beyond the focus of this article; however, because patients are often interested in the subject, physicians should be familiar with the debate. The primary proposed medical uses of cannabinoids are shown in Table 6.1,4,7,9,22,25

Advocates of medicinal marijuana use point out that the estimated ratio of lethal dose to therapeutic dose is about 20,000:1.25 Much of the controversy surrounding this issue could be minimized if researchers could isolate or develop specific cannabinoids that are medically efficacious and have little or no potential for abuse.

Identifying Patients in Need of Treatment

Identifying patients with a marijuana-related disorder can be difficult, because abuse and associated problems commonly develop slowly. Often, patients do not recognize that they have a problem or do not want to give up their drug use. In addition, they may try to hide their problem from parents, physicians and other authority figures.

Unexplained deterioration in school or work performance may be a red flag for drug abuse. In addition, problems with or changes in social relationships (such as spending more time alone or with persons suspected of using drugs) and recreational activities (such as giving up activities that were once pleasurable) may indicate drug abuse. Information from concerned parents or spouses is often helpful in sorting out a differential diagnosis.

Although marijuana abuse in adolescents and young adults is of particular concern, it should not be overlooked in other patient groups. For example, persons with certain psychiatric disorders (such as bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder), those who are under severe emotional distress and those who have chronic pain might be at increased risk. Ultimately, patients who need treatment will be identified through direct disclosure of marijuana-related problems by the patient, a positive urine drug screen, or identification by legal, school or employment authorities.

treatment strategies

An estimated 100,000 people in the United States seek treatment for marijuana dependence annually.13 Overcoming the minimization of marijuana-related problems in an environment of common use, mixed messages and peer pressure is the first challenge physicians face. Although many patients use marijuana, few initiate discussions about it in a medical setting. Thus, physicians may need to directly address the issue when appropriate. Interventions to be considered include education, monitoring of drug use, strengthening of social support, treatment of possible comorbid psychiatric disorders and referral to a substance abuse treatment program (Table 7).

Education about the adverse effects of marijuana may deter some patients but certainly not all. For instance, some people may not have considered the weight gain related to marijuana use.20,21 Others may be concerned about possible adverse effects of cannabinoids on the reproductive system.1,4,7,22,24-26,31,32 Education and other forms of prevention may be particularly important in school-age children because of the effects marijuana may have on motivation and behaviors that affect self image, social relationships and academic performance.7,17

Acute panic reactions and flashbacks during marijuana intoxication can usually be handled with supportive therapy in a calming environment. In severe cases, low-dose anxiolytic medication may be needed.1 Withdrawal from marijuana does not require medical intervention.

Patients who have a problem with marijuana abuse or dependence should be referred to a comprehensive substance abuse treatment program. Such programs are designed to prevent relapse and often consist of complete substance abuse and psychiatric evaluations, laboratory testing (such as testing for human immunodeficiency virus infection, urine drug screens, liver status, etc.), group therapy, education, social services, individual counseling, promotion of 12-step programs (such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous) and treatment of co- morbid psychiatric illness. Often, these programs involve individual reflection about how problems with substance abuse develop, the direct and indirect costs of substance abuse, biopsychosocial triggers for substance use, relapse prevention strategies, ways to enhance coping skills and spiritual issues.

REFERENCES

1.Losken A, Maviglia S, Friedman LS. Marijuana. In: Friedman LS, et al., eds. Source book of substance abuse and addiction. Baltimore, Md.: Williams & Wilkins, 1996:179-87.

2.Onaivi ES, Chaudhuri G, Abaci AS, Parker M, Manier DH, Martin PR, et al. Expression of cannabinoid receptors and their gene transcription in human blood cells. Prog Neuropsychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry [In press].

3.Cohen G, Fleming NF, Glatter KA, Haghigi DB, Halberstadt J, McHugh KB, et al. Epidemiology of substance use. In: Friedman LS, et al., eds. Source book of substance abuse and addiction. Baltimore, Md.: Williams & Wilkins, 1996:23-46.

4.Schuckit MA. Cannabinols. In: Drug and alcohol abuse: a clinical guide to diagnosis and treatment. 3d ed. New York: Plenum Medical, 1989:143-57.

5.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA 1990;264:2511-8.

6.Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K, Chen K. Stages of progression in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: further evidence for the gateway theory. J Stud Alcohol 1992;53:447-57.

7.Hollister LE. Cannabis-1988. Acta Psychiatr Scand (Suppl) 1988;345:108-18.

8.Onaivi ES, Green MR, Martin BR. Pharmacological characterization of cannabinoids in the elevated plus maze. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1990;253:1002-9.

9.Gurley RJ, Aranow R, Katz M. Medicinal marijuana: a comprehensive review. J Psychoactive Drugs 1998;30:137-47.

10.Onaivi ES, Chakrabarti A, Chaudhuri G. Cannabinoid receptor genes. Prog Neurobiol 1996;48:275-305.

11.Stella N, Schweitzer P, Piomelli D. A second endogenous cannabinoid that modulates long-term potentiation. Nature 1997;388:773-8.

12.Lu R, Hubbard JR, Martin BR, Kalimi MY. Roles of sulfhydryl and disulfide groups in the binding of CP-55,940 to rat brain cannabinoid receptor. Mol Cell Biochem 1993;121:119-26.

13.Wickelgren I. Marijuana: harder than thought? Science 1997;276:1967- 8.

14.Tanda G, Pontieri FE, Di Chiara G. Cannabinoid and heroin activation of mesolimbic dopamine transmission by a common mu1opioid receptor mechanism. Science 1997;276:2048-50.

15.Musty RE, Reggio P, Consroe P. A review of recent advances in cannabinoid research and the 1994 International Symposium on Cannabis and the Cannabinoids. Life Sci 1995;56:1933-40.

16.Hubbard JR, Workman E, Marcus L, Felker B, Capell L, Smith J, et al. Differences in marijuana use across psychiatric diagnoses. Reasons they use, the side effects they experience. Poster B37, The Future of VA Mental Health Research. National Foundation for Brain Research, Washington, D.C., 1993.

17.Smart RG, Adlaf EM. Adverse reactions and seeking medical treatment among student cannabis users. Drug Alcohol Depend 1982;9:201-11.

18.Benowitz NL, Jones RT. Cardiovascular effects of prolonged delta-9- tetrahydrocannabinol ingestion. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1975;18:287-97.

19.Gottschalk LA, Aronow WS, Prakash R. Effect of marijuana and placebo-marijuana smoking on psychological state and on psychophysiological cardiovascular functioning in anginal patients. Biol Psychiatry 1977:12:255-66.

20.Greenberg I, Kuehnle J, Mendelson JH, Bernstein JG. Effects of marijuana use on body weight and caloric intake in humans. Psychopharmacology [Ber] 1976;49:79-84.

21.Hollister LE. Hunger and appetite after single doses of marihuana, alcohol, and dextroamphetamine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1971;12:44-9.

22.Nahas G. Biomedical aspects of cannabis usage. Bull Narc 1977;29:13- 27.

23.Weil AT. Adverse reactions to marihuana. Classification and suggested treatment. N Engl J Med 1970; 282:997-1000.

24.Nahas GG. Cannabis: toxicological properties and epidemiological aspects. Med J Aust 1986;145:82-7.

25.Lowinson JH, Ruiz P, Millman RB, eds. Marihuana. In: Substance abuse: a comprehensive textbook. 2d ed. Baltimore, Md.: Williams & Wilkins, 1992.

26.Murphy LL, Gher J, Steger RW, Bartke A. Effects of delta 9- tetrahydrocannabinol on copulatory behavior and neuroendocrine responses of male rats to female conspecifics. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1994;48:1011-7.

27.Hollister LE. Health aspects of cannabis: revisited. Intern J Neuropsychopharmacology 1998;1:71-80.

28.Kleinman PH, Wish ED, Deren S, Rainone G, Morehouse E. Daily marijuana use and problem behaviors among adolescents. Int J Addict 1988;23:87-107.

29.Rouse BA, Ewing JA. Marijuana and other drug use by women college students: associated risk taking and coping activities. Am J Psychiatry 1973;130:486-91.

30.Grinspoon L, Bakalar JB. Marijuana as medicine. A plea for reconsideration. JAMA 1995;273:1875-6.

31.Legido A. Intrauterine exposure to drugs [Spanish]. Rev Neurol 1997;25:691-702.

32.Witorsch RJ, Hubbard JR, Kalimi MY. Reproductive toxic effects of alcohol, tobacco and substances of abuse. In: Witorsch RJ, ed. Reproductive toxicology. 2d ed. New York: Raven, 1995:283-318.

The Authors

JOHN R. HUBBARD, M.D., PH.D., is an associate professor of psychiatry in the Division of Addiction Medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., and director of the Substance Abuse Treatment Program at the Nashville Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Dr. Hubbard received his medical degree and a Ph.D. in biochemistry from Virginia Commonwealth University Medical College of Virginia School of Medicine, Richmond. He is board-certified in psychiatry and addiction psychiatry.

SHARONE E. FRANCO, M.D., is currently a staff psychiatrist at Western Mental Health Institute in Bolivar, Tenn. Dr. Franco received her medical degree from the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and completed her residency at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, where she was chief resident.

EMMANUEL S. ONAIVI, PH.D., is assistant professor of pharmacology and psychiatry at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville. Dr. Onaivi received his Ph.D. in neuropharmacology at the University of Bradford, England.

Address correspondence to John R. Hubbard, M.D., Ph.D., Nashville Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Dept. of Psychiatry, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN 37212. Reprints are not available from the authors.

COPYRIGHT 1999 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group