* CLINICAL QUESTION

Does tight blood pressure control improve visual outcomes in diabetic hypertensive patients?

* BOTTOM LINE

Tight blood pressure control results in a small benefit in the prevention of blindness, with a number needed to treat of 1000 per year. Tight control was also associated with a reduction in loss of visual acuity after 9 years (but not with shorter durations of follow-up) and an increase in the likelihood of cataract extraction. (LOE=1b)

* STUDY DESIGN

Randomized controlled trial (double-blinded)

* ALLOCATION

Concealed

* SETTING

Outpatient (any)

* SYNOPSIS

This is yet another report from the landmark United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) of patients with type 2 diabetes. In this substudy, 1148 hypertensive patients with diabetes were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to tight or loose control of blood pressure, with target blood pressures of 150/85 mm Hg or 200/105 mm Hg, respectively. The loose control target was changed to 185/105 mm Hg midway through the study.

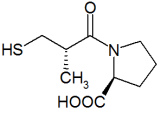

Patients in the active treatment group were further randomized to receive either captopril (Capoten) or atenolol (Tenormin) in standard doses, increased until control was achieved, with furosemide (Lasix), nifedipine (Procardia), methyldopa (Aldomet), or prazosin (Minipres) added (in that order), if needed. The degree of retinopathy was evaluated at enrollment and every 3 years thereafter. Allocation to groups was concealed, outcome assessment was blinded, and analysis was by intention to treat.

Patients were followed for a median of 9.3 years. The average blood pressure in the tight control group was 144/82 mm Hg and in the loose control group was 154/87 mm Hg. The mean glycohemoglobins were similar in these groups: 7.2% during the first 4 years of the study, and 8.2% to 8.3% for the final 4 years. The tight control group had fewer microaneurysms after 4.5 years follow-up (23.3% vs 33.5%; number needed to treat [NNT] =10), fewer hard exudates, fewer cotton-wool spots, less progression of retinopathy, and less need for photocoagulation. These are all disease-oriented endpoints and do not necessarily result in significant worsening of vision or visual loss.

The primary patient-oriented outcomes are blindness and reduction in visual acuity. Visual loss in one eye was less likely in the tight control group, occurring in 2.4% of patients in the tight control group compared with 3.1% in the loose control group (P=.046). This corresponds to an absolute increase in risk with loose control of approximately 1 per 1000 patient-years of treatment. After 9 years, there was a lower likelihood of deterioration in either eye in the tight control group (20.5% vs 32.8%; NNT=8). However, there was no significant difference in the reduction of vision as assessed by the better eye.

An interesting finding, not otherwise commented on in the manuscript, was that 36 patients in the tight control group required cataract extraction compared with only 14 in the loose control group. We are not given the statistical significance of this difference, but judging by the other differences it almost certainly was significant.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Risks of progression of retinopathy and vision loss related to tight blood pressure control in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Ophthalmol 2004; 122:1631-1640.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Dowden Health Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group