The Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood pressure announced its latest guidelines last spring. People with blood pressures that were normal or high normal, as recently as three months ago, now have a condition called prehypertension. People in this new category have blood pressures of 120 to 139 millimeters of mercury systolic (top number) or 80 to 90 diastolic (bottom number), according to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute which introduced the news at a May 14th press conference.

Michael Alderman, MD, is a past president of the American Society of Hypertension. A professor of medicine and population health sciences at Albert Einstein School of Medicine, Bronx, New York, Dr. Alderman has co-authored many studies related to hypertension. He is interviewed about the new guidelines.

With the new guidelines, overnight, an estimated 50 million Americans become potential patients. Is it too cynical to think that drug industry influence is at work?

Dr. Alderman: There's no doubt that there are elements of these new guidelines that the pharmaceutical industry will be gratified to read. As you note, the designation of prehypertension will raise the level of possibility that many among this new 50 million will be given drugs. Had the guidelines focused on global [overall] risk assessment, including people [with other risks for heart disease] then this new category would surely have made sense.

The recommended lifestyle changes, such as weight loss, exercise, and restriction of sodium and alcohol, are known to result in only small decreases in blood pressure. So everyone will eventually end up on drugs, right?

Dr. Alderman: That's my concern. Despite these [longstanding] recommendations, Americans have been stretching at the middle. So why continue to recommend a strategy that appears to be unsuccessful? There's an enormous amount of evidence that very intensive one-onone intervention and counseling with a dietitian or a behaviorist can achieve modest effects, but it is 30% more expensive than taking diuretics. What's more, lifestyle effects seem to attenuate over time. There is this notion that there's a moral superiority to lifestyle interventions. Our goal is to save lives in the least intrusive and least expensive way possible.

What new evidence was produced to show that artery damage and an increased risk of heart disease begins at blood pressure in the 120 to 139 mm Hg /80 to 90 mm Hg range?

Dr. Alderman: For at least 20 years, there has been good evidence that the risk of cardiovascular events increases with increasing blood pressure. From a very low level there's a continuous increase in the risk of heart disease. The question is, of course, where does the benefit from lowering blood pressure come. The Joint National Committee has arbitrarily picked a new level--instead of 140, now it's 120. There's no more evidence that that's the place to go than there was before. Since I went to medical school--and I graduated in 1962--the continuous relationship of [blood] pressure to [cardiovascular] events has been known. The level at which we called people hypertensive is arbitrary, and that level has constantly been reduced since 1910. The effect of moving that level from 140 to 120 is to include 50 million Americans into something labeled prehypertension. That's equal to the total number of people that we were calling hypertensives before. So now we have medicalized 100 million Americans instead of 50 million.

How do you determine when to be concerned about high blood pressure?

Dr. Alderman: I--and most modern-thinking doctors--believe that blood pressure is only one part of the determination of your global [overall] risk for cardiovascular disease. The concern is about risk for stroke and heart attack, and that is the sum total of many factors, including blood pressure. There are people with rather low blood pressure who are at a rather high risk for stroke and heart attack on the basis of their cholesterol, cigarette smoking, enlarged heart, kidney disease--a whole range of things that might increase the risk for a cardiovascular event.

Those people should have their blood pressure lowered--almost whatever their blood pressure is. There are studies to prove this because lowering blood pressure does lower their risk, even if the blood pressure is 125. If your risk is, let's say, 50 chances out of a 100 that you'll have a heart attack, and you can lower your risk by 25%--that's a good buy. But if your blood pressure is 125 and you have nothing else, your risk is almost entirely a result of your age--then your additional risk is very small and not likely to be meaningfully reduced by lowering blood pressure. Wise doctors and patients will recognize that simply looking at the blood pressure level is no way to decide on the need for an intervention. It's the total risk for cardiovascular events that matters.

What about the person who, other than age, has no other risk for heart disease, but his blood pressure is high, say 180 over 110?

Dr. Alderman: Then his risk, on the basis of his blood pressure, is high enough to justify drug treatment. What I'm worried about are those people between 120 and 139 who have now been accused of having prehypertension. There's no evidence to show that people in that range, who have no other risk factors, will benefit [from drug treatment]. If they have other risk factors, that's a different story. But that's not what the new guidelines say.

According to the new guidelines, if you are prehypertensive, you should lower your blood pressure with lifestyle changes. That, as we have already discussed, is not very likely to work. So what will the patient say, "I'm a failure--doomed to whatever prehypertension dooms you to," or "Do I take one of these drugs like low-dose diuretics that cost about a penny a day and have been proven to save lives?" Well, the new guidelines are silent on that important question which millions of Americans should be asking.

You said that treatment should start with diuretics. Is it a stepped approach that is recommended, starting with diuretics and if they don't work, you move up to beta-blockers, and so forth?

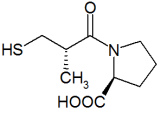

Dr. Alderman: Yes, for most people, I think that's right. However, there are specific situations, such as kidney disease characterized by leaking protein, where other drugs are useful, for example, the angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitors * [e.g,, Capoten, Vasotec] and the A2 receptor blockers [e.g., Atacand, Avapro]. Clinical trials say that's the best. But for the garden variety, uncomplicated hypertension--about 70% of all people with hypertension--starting with a diuretic is right. And there's no evidence that there is anything better, though you have to worry a little bit about diabetes and loss of potassium with diuretics. Reasonable monitoring, however, should cover that risk.

You have searched the scientific evidence related to sodium restriction and consistently found no cardiovascular benefit. If so, why do the guidelines continue to tell people with high blood pressure to cut back on the salt intake?

Dr. Alderman: The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute has been heavily invested in sodium restriction for 30 years. It's hard to change your views. Several things are becoming clear: When you lower sodium intake in some people, it lowers blood pressure. But for most people, it doesn't. And in a few people, it actually raises blood pressure. There's tremendous variation, and that's understandable because we are all so different. For example, some of us work hard, sweat, exercise; and people who sweat a lot need a lot of salt to keep even. Others have genetic differences in the way they handle salt. There are seven individual single gene conditions in which salt and blood pressure are affected. In two of them, there are salt-losing situations--if you don't eat enough salt, your blood pressure falls and you die. In five others, you eat salt and your blood pressure goes up. Thus, we are a diverse crowd with behavioral, genetic, and environmental differences in the way salt intake affects us.

Where does that leave us?

Dr. Alderman: Scientists have generally moved the discussion beyond the effect of salt on blood pressure. Everybody agrees that if you treat 100,000 people with a low-salt diet, you would probably lower the average blood pressure a millimeter or two of diastolic and three or four systolic. And everybody agrees that that benefit would be unevenly distributed throughout the population. But the question is: Is the price paid [harm caused] by lowering the salt to attain that blood pressure going to be greater than the benefit? The reason I ask that question is this: lowering salt to reduce blood pressure has other effects. It stimulates the renin angiotensin system and increases sympathetic nerve activity, which raises the pulse rate. Both of these things adversely affect the heart. And it decreases insulin sensitivity--that's bad for you too.

So on the one hand, your blood pressure levels falls; on the other hand, you have all these other things. The effect on human health is the sum total of all those things. That's why [doctors should] test interventions. And that's why we demand clinical trials to make sure we're not hurting people more than we help them. My guess is that, in view of the genetic, behavioral, and environmental heterogeneity of the population, it is not likely that one level of sodium intake will prove to be best for all Americans.

You have suggested that doctors tell people to restrict their salt intake but never test them again.

Dr. Alderman: They virtually never do. The government says it's a good thing to do: put people with hypertension on a low-salt diet. [Hardly any] doctors tell them to collect their urine for 24 hours, which is a reasonable way to measure salt intake. It's hard to tell how much salt you eat because most of it comes in bread, cake, etc. Only 10-15% of your salt comes out of a saltshaker.

I'd like to end by asking you what you think of this statement from the European Heart Journal in 2000, "No randomized clinical trial has ever demonstrated any reduction of the risk of either overall or cardiovascular death by reducing systolic blood pressure from thresholds to below 149 mmHg"?

Dr. Alderman: That's correct. Although since then, I believe that the level has dropped to 140 mmHg. But it has been shown in high-risk patients that a small reduction in blood pressure, even at lower pressure can produce a real benefit. Half the people in the HOPE [Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation] trial didn't have hypertension by our 140 mm or 120 mm definitions, yet they benefited from the addition of an ACE inhibitor [e. g., Altace, Capoten] which lowered blood pressure a few mmHg. Modern thinking, as shown in the recent publication of the European treatment guidelines, incorporates hypertension into a global risk. They get away from arbitrary definitions of high blood pressure and try to make a more comprehensive, patient-centered approach to treatment.

* Each of the anti-hypertensive drug classes mentioned in this interview has numerous brand names for each medication. Only two are given as examples.

COPYRIGHT 2003 Center for Medical Consumers, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group