People with insulin-dependent (juvenile-onset) diabetes - a disease that interferes with the metabolism of sugar, run about a 35 percent risk of getting kidney disease, or nephropathy.

Nephropathy, a progressive condition, can lead to complete kidney failure within 10 years, Diabetics with this complication are nine times more likely to die prematurely than diabetics without it.

However, a new study shows that a drug commonly used to control high blood pressure may also offer some protection against nephropathy.

Edmund J. Lewis, a physician at Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke's Medical Center in

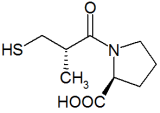

Chicago, and his colleagues report that captopril -- a type of angiotensin-convertlag-enzyme (ACE) inhibitor- "protects renal function in insulin-dependent diabetic nephropathy and is significantly more effective than blood-pressure control alone." Their report appears in the Nov. 11 NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE.

"We were struck by how positive the study's results are," Lewis says. "We found that ACE inhibitors retard kidney disease at all stages studied. The fact that there was a positive effect in patients with the most advanced disease was a surprise. Most people believe that once kidney disease has gone far, there's no stopping it."

The researchers studied 409 diabetics between December 1987 and October 1990. The patients, 18 to 49 years old, had insulin-dependent diabetes for at least seven years, with an onset before age 30, plus kidney disease, measured by protein excretions in their urine and elevated concentrations of serum creatinine, indications of kidney damage. In the doubleblind study, 207 patients took 25 milligrams of captopril three times a day, while 202 patients received placebo pills.

A total of 301 patients completed the study as planned; 58 patients required additional follow-up or were removed from the study for health reasons; and 50 underwent kidney dialysis, had a kidney transplant, or died.

Among the conclusions: "We found that captopril significantly retarded the rate of loss of renal function in this group of patients with diabetic nephropathy. In the captopril group, the risk of a doubling of the serum creatinine concentration was reduced by almost one-half, as was the combined risk of death, dialysis, and transplantation," the researchers state. And captopril's protective mechanism appears "independent of its antihypertensive properties."

The researchers believe that captoprii, like other ACE inhibitors, eases the pressure within the kidneys' many small filters, called glomeruli. "The blood vessels draining these filters, for unknown reasons, constrict in the diabetic state:' Lewis says. "This constriction causes the giomeruli's internal pressure to rise, which seems to cause scarring that leads to progressive renal failure."

A hormone produced in the kidney, called angiotensin II, controls this renal constriction, says Lewis. Captopril inhibits the hormone's production, thus allowing the pressure within the glomeruli to fall. Whether other ACE inhibitors will perform equally well remains an open question, he adds, "but the rationale behind the study suggests they could. We studied captopril because we'd had the most experience with it, but we don't know yet how other ACE inhibitors will do.

These findings could affect the treatment of the 14 million U.S. diabetics and the 100 to 150 million worldwide, says Sara King of the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation. About 10 percent of diabetics develop insulin-dependent diabetes, usually in childhood; the rest develop noninsulin-dependent diabetes, she notes. Although this study focused on juvenileonset diabetics, Lewis believes captopril may benefit adult-onset patients as well.

It's possible that diabetic nephropathy is now a preventable disease," says Nell Kurtzman, president of the National Kidney Foundation, "provided we start treatment early enough."

COPYRIGHT 1993 Science Service, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group