Many patients with depression are now recognized as having bipolar disorder, a chronic biphasic mood disorder with episodes of both depression and mania or hypomania. Successful management of bipolar disorder requires suppression of acute mania, treatment of acute depression, and prevention of relapse into either condition. No single medication can achieve all of these objectives. McIntyre and colleagues examined evidence supporting the efficacy of each of the medications commonly used to treat bipolar disorder. Their review article stresses the need for individualization of therapy and adaptation to the changing needs of each patient over time.

Lithium was the earliest mood-stabilizing medication and still is used extensively. The efficacy of lithium is well established in patients who are in manic states, and it is known to reduce the rates of suicide. Lithium is most effective in patients who have little comorbidity and do not cycle rapidly. Patients who are likely not to respond well to lithium include those with frequent previous episodes, rapid cycling, depressive and anxious symptoms during the manic phase, substance abuse, and medical conditions.

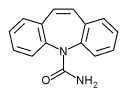

The second-generation antiepileptic drugs divalproex and carbamazepine are highly effective in patients with acute mania, but have less effect in patients with depression and in the prevention of symptom recurrence. These drugs are useful in patients who do not respond to lithium, but their use is limited by side effects such as weight gain and sedation, as well as multiple drug-drug interactions and the need to monitor blood levels of the drug along with hepatic and hematologic indexes.

Conversely, the third-generation antiepileptic drug lamotrigine is effective in the treatment of depression and the prevention of recurrence, and does not require blood monitoring. The major problem with lamotrigine is a rash that develops in up to 10 percent of patients and can progress to Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Fewer data are available about other third-generation antiepileptic drugs. Gabapentin is useful for anxiety symptoms, and topiramate may improve depressive states. Oxcarbazepine may provide many of the antimania and antidepressant effects of carbamazepine with fewer side effects and drug interactions.

The conventional antipsychotic agents, such as haloperidol, have been used to treat acute mania, but their use is limited by dysphoria, tardive dyskinesia, and extrapy-ramidal effects. The novel antipsychotics, such as olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine, have direct antidepressant effects and are highly effective against mania. These actions appear to be independent of the anti-psychotic effects of these drugs, and most bipolar patients benefit at low dosages (e.g., 10 to 15 mg of olanzapine, 2 to 4 mg of risperidone, 400 to 800 mg of quetiapine). This group of drugs may be particularly effective as adjunctive therapy with antidepressants in patients with bipolar depression and in maintenance therapy, when combined with lithium or divalproex. The biggest disadvantage of the novel antipsychotics is weight gain; lipid and glucose abnormalities also occur.

Although evidence is limited, antidepressants are commonly used for short periods (up to two months) to treat patients in the depressed phase of bipolar disorder. The danger of precipitating mania is reported to be greatest with tricyclic agents.

The authors conclude that a combination of medical and psychosocial strategies is required for successful treatment of bipolar disorder. Patients frequently have problems adhering to therapy and require education and assistance with lifestyle issues to cope with this lifelong condition.

McIntyre RS, et al. Treating bipolar disorder. Evidence-based guidelines for family medicine. Can Fam Physician March 2004;50:388-94.

COPYRIGHT 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group