Study objective: To determine the appropriate chemotherapy regimen for inoperable, chemotherapy-naive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in elderly patients.

Setting: National teaching hospital in Taiwan.

Design: We retrospectively analyzed data from our clinical trials for a total of 270 patients and compared them with the data from other studies, addressing the elderly in particular or providing subgroup information on age, to analyze the feasibility of current chemotherapy options for elderly patients and possible alternative approaches.

Results: The response rates and median survival times of fit elderly patients with NSCLC who were receiving appropriate new anticancer drugs for chemotherapy, including single-agent or combination treatment, were no worse than those of younger patients, and the response rates may have been even higher in the elderly patients, while survival time was slightly poorer in this group. The risk of adverse side effects, such as myelosuppression and peripheral neurnpathy, may be higher in elderly patients, who also visit the hospital more frequently. Some items on the lung cancer symptom scale for elderly patients were rated as being slightly worse than those for younger patients after chemotherapy.

Conclusion: Advanced age alone should not preclude chemotherapy. New single-agent drugs, and non-platinum-based or platinum-based doublets, can all be considered as appropriate treatment for selected fit elderly patients with advanced NSCLC. (CHEST 2005; 128:132-139)

Key words: elderly; gemcitabine; non-small cell lung cancer; taxane; vinorelbine

Abbreviations: ANOVA = analysis of variance; ELVIS = Elderly Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Italian Study Group; NSCLC = non-small-cell lung cancer; OPD = outpatient department

**********

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the world. It is a typical disease of elderly patients, with a peak incidence at around 70 to 80 years of age. (1,2) There is more squamous cell carcinoma, at a relatively early staging among this group, and a higher proportion of elderly patients refuse treatment or receive incomplete treatment, when compared with younger patients. (2,3) The reason for the higher percentage of early-stage patients is probably the more frequent chest screening, due to the presence of comorbid disease, and the higher frequency of squamous cell carcinoma, which has a tendency toward local invasion instead of distant metastases. Lung cancer in elderly patients is often treated suboptimally due to the presence of comorbid diseases that prohibit part or most chemotherapy options, and because the patients subjectively feel that they are doing well and have survived long enough, thus needing no treatment. Therefore, investigative procedures and treatments are undertaken less frequently in elderly patients.

Usually, when a man is [greater than or equal to] 60 years of age, we feel that he is old. When he is [greater than or equal to] 80 years of age, we consider him to be very old. In clinical trials, we usually consider those persons who are [greater than or equal to] 70 years of age to be elderly, and those < 70 years of age to be nonelderly. However, the best way to define elderly for daily patient care is "when the heath status of a patient population begins to interfere with the oneologic decision-making guidelines." (4)

Investigators from the Southwest Oneology Group retrospectively analyzed the percentage of elderly patients participating in their cancer treatment trials, and found that elderly patients [greater than or equal to] 65 years of age accounted for 66% of the lung cancer study population but only 39% of those participating in their clinical trial. (5) This underrepresentation of elderly patients is even more marked in those [greater than or equal to] 70 years of age. For example, one third to 40% of lung cancer patients are [greater than or equal to] 70 years of age; however, they accounted for only 15% of the study population in the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 5592 trial. (6)

In the present study, we used data from our clinical trials and others to analyze the feasibility of current chemotherapy options for elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

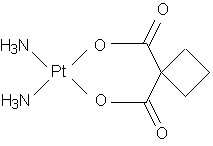

We retrospectively reviewed and analyzed three clinical trials using new anticancer drugs against chemotherapy-naive NSCLC patients, which we undertook between 1998 and 2002 (total of 270 patients). The three trials included a vinorelbine-plus-gemcitabine study (40 patients), (7) a paclitaxel-phis-carboplatin vs paclitaxel-phis-gemcitabine study (90 patients), (8) and a cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy study comparing weekly vinorelbine therapy and weekly paclitaxel therapy (140 patients). (9)

Patients were classified into a nonelderly group (ie, < 70 years of age) or an elderly group ([greater than or equal to] 70 years of age). The response rate, toxicity profiles, survival times, and lung cancer symptom scale scores were compared between these two groups of patients. The response rate and survival time were both analyzed with an intention-to-treat principle. Overall survival time and time-to-disease progression were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier estimation method and log-rank test. The time-to-disease progression was calculated from the date of initiation of treatment to the date of disease progression or death. If disease progression had not occurred by the time of this analysis, progression-free survival was considered to have been censored at the time of the last follow-up visit. Survival time was measured from the date of the initiation of treatment to the date of death. If death had not occurred, survival time was considered to have been censored at the last follow-up time. All comparisons of clinical characteristics, response rates, toxicity incidences, days spent visiting or staying in the hospital, cost of the treatment, and changes in the lung cancer symptom scale scores were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA).

RESULTS

The first study was performed with a vinorelbine-plus-gemcitabine treatment in chemotherapy-naive NSCLC patients. (7) From March to September 1998, 40 patients were enrolled into the study. Vinorelbine, 20 mg/[m.sup.2], and gemcitabine, 800 mg/[m.sup.2], were administered on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4 weeks. Seventeen patients (42.5%) were [greater than or equal to] 70 years of age, and 23 patients (57.5%) were < 70 years of age. There was no significant difference in the clinical characteristics between the two age groups of patients (Table 1). The older patients tolerated the treatment well, with a median of five cycles of treatment. They had a better response rate (88% vs 60.9%) but a slightly poorer survival time (median survival time, 10 vs 12.5 months, respectively) than the younger patients, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (Table 2, Fig 1). Myelosuppression and fatigue were more severe in the elderly patients; however, statistical significance was reached only for anemia (p = 0.01, Table 2).

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

The second study was a phase II randomized study comparing therapy with paclitaxel plus carboplatin vs therapy with paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in chemotherapy-naive NSCLC patients aged < 80 years of age. (8) From 1999 to 2000, 90 patients were enrolled into the study. Almost half of them were [greater than or equal to] 70 years of age (Table 3). In one arm of the study, paclitaxel, 175 mg/[m.sup.2], and carboplatin at an area under the curve of 7 were administered on day 1 every 3 weeks, while in the paclitaxel-phis-gemcitabine arm, paclitaxel, 175 mg/[m.sup.2], was administered on day 1 and gemcitabine, 1000 mg/[m.sup.2], was administered on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks. When we consider these two non-cisplatin-based treatment groups together, there were more female patients in the group of patients who were < 70 years of age (p = 0.004), otherwise, there was no significant difference in clinical characteristics (Table 3). The treatment response rate was higher among the older patients (50% vs 30.4%, respectively), although the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.173). Elderly patients tolerated treatment well, with a median of four cycles of treatment. Their survival time was similar to that of the younger patients (Table 4, Fig 2). The leukopenia rate was higher in the younger patients. The incidences of anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neuropathy were higher in the elderly patients. However, statistical significance was reached only for anemia (p < 0.001). The elderly patients needed more outpatient department follow-up and expended more days visiting or staying in the hospital (Table 4). There was no difference in the total cost of treatment, including the costs of drugs, administration, examination, and outpatient clinic fees, and fees associated with emergency department visits, between the two age groups (Table 4). However, there was a small, but significant, difference in the costs related to emergency department visits.

[FIGURE 2 OMITTED]

The third study (9) was a cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy study comparing weekly therapy with vinorelbine and weekly therapy with paclitaxel. From 2000 to 2002, 140 patients were enrolled into the study, and half of them were [greater than or equal to] 70 years of age (Table 5). The treatment consisted of cisplatin, 60 mg/[m.sup.2], which was administered on day 15, plus vinorelbine, 23 mg/[m.sup.2], or paclitaxel, 66 mg/[m.sup.2], which was administered on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4 weeks. The patients' clinical characteristics were not different by age group, except there were significantly more female patients in the younger group (p < 0.001) [Table 5]. Both age groups had the same response rate (38.6%). The rate of all hematologic toxicities was significantly higher in the older patients. Severe fatigue and peripheral neuropathy were also more common in the older patients (Table 6). In the efficacy analysis, the older patients tolerated treatment well, despite the fact that they had more treatment-induced toxicity; both age groups had received four cycles of treatment (Table 6). Older patients had a slightly poorer survival time, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (Table 6, Fig 3). The lung cancer symptom scale scores showed significantly worse appetite, fatigue, dyspnea, disease severity, daily activity, and quality of life after treatment. However, the difference in the deterioration of the scale scores was very small between the two age groups (Table 7).

[FIGURE 3 OMITTED]

DISCUSSION

It has been shown that age has an impact on the diagnosis and treatment of NSCLC. A higher proportion of elderly patients has poor performance status, early-stage disease, and squamous cell carcinoma, whereas, in contrast, these patients have undergone fewer imaging studies, and fewer of them have received active treatment. (6,10,11)

Since 1996, phase II single-agent vinorelbine treatment studies (12,13) have shown relatively good response rates and survival times in chemotherapy-naive elderly patients. The Elderly Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Italian Study group (ELVIS) performed a phase III randomized study (14) comparing vinorelbine treatment with the best supportive care alone in elderly NSCLC patients [greater than or equal to] 70 years of age. The response rate was nearly 9.0% in the patients receiving vinorelbine treatment. The median survival time of 28 weeks in the vinorelbine arm was significantly higher than that of 21 weeks achieved with supportive care only. Vinorelbine treatment also improved cancer-induced symptoms, such as dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, and pain. (14) II studies (15-17) of single-agent gemcitabine treatment in chemotherapy-naive elderly patients with NSCLC also revealed response rates between 21.7% and 38.5%, a median survival time ranging from 6.8 to 9 months, and an improved quality of life.

Gemcitabine in combination with vinorelbine is the most common nonplatinum combination chemotherapy that is used in elderly patients. Phase II studies (18,19) of gemcitabine plus vinorelbine in elderly patients generally have shown good response rates, low toxicity profiles, and long survival times. The Multi-center Italian Lung Cancer in the Elderly Study, which was conducted by Gridelli et al (20) and focused on determining whether polychemotherapy with gemcitabine plus vinorelbine is more effective than single-agent therapy with vinorelbine or gemcitabine, revealed that there was no difference found in survival times between patients who received single-agent treatment and those who received combination treatment. They concluded that combination therapy with gemcitabine plus vinorelbine did not improve patient outcome compared to single-agent treatment, and that single-agent treatment with vinorelbine or gemcitabine should remain a standard treatment for elderly patients. (20) Our study of vinorelbine-plus-gemcitabine chemotherapy in chemotherapy-naive NSCLC patients showed that the older patients had a better response rate and tolerated the treatment well, despite the fact that myelosuppression and fatigue were relatively more severe in the elderly patients, compared to the younger patients (Table 2). Our another phase II randomized study comparing therapy with paclitaxel plus carboplatin to therapy with paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in NSCLC patients (8) also showed that elderly patients tolerated these noncisplatin treatments well (Table 4).

There have been a number of studies using platinum-based combination chemotherapy. One, the Eastern Cooperative Ontology Group 5592 study, (6) was a randomized cisplatin-based chemotherapy study comparing different doses of paclitaxel with etoposide. In this study, 15% of patients were [greater than or equal to] 70 years of age. Leukopenia and neuropsychiatric toxicity were significantly higher among the elderly patients. However, there was no significant difference in response rate, time to disease progression, median survival time, or 1-year and 2-year survival rates between these two age groups (ie, < 70 or [greater than or equal to] 70 years of age). Kelly et al (21) retrospectively reviewed two cisplatin-based chemotherapy studies (22,23) that were performed by the Southwest Ontology Group. One was a paclitaxel-plus-carboplatin therapy vs vinorelbine-plus-cisplatin therapy study, (22) and the other compared cisplatin therapy with and without vinorelbine. (23) They found that there was no significant difference in hematologic toxicity, nonhematologic toxicity, or maximal toxicity between the young and old patients, although the incidence of toxicity of grades 3 to 5 was slightly higher in the older age group. Age also had no effect on time to disease progression and survival time, although survival time was slightly shorter among the older patients.

In our cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy study comparing weekly therapy with vinorelbine to weekly therapy with paclitaxel, patients in both age groups had the same response rate (38.6%) [Table 6]. (9) The older patients tolerated treatment well (both age groups had received a median of four cycles of treatment), despite the fact that they had more treatment-induced toxicity and a slightly poorer survival time (Table 6, Fig 3). However, there was a small, statistically significant, worsening effect on appetite, fatigue, dyspnea, disease severity, daily activity, and quality of life in elderly patients after treatment compared to the younger patients (Table 7).

The effectiveness of chemotherapy can be classified into areas of response rate, toxicity profile, survival time, quality of life, and cost-effectiveness. In our study, (8) we found that elderly patients required more frequent OPD visits, and that they visited the hospital (including OPD and emergency department visits, and hospitalization) more frequently during their treatment course than did younger patients (Table 4). When receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy, (9) the elderly patients had a significant, but small, difference in the deterioration of appetite, fatigue, dyspnea, and disease severity, and a lessening of daily activity and quality of life, compared to the younger patients (Table 7). Despite the fact that elderly patients need more frequent hospital visits and are more likely to experience lung cancer symptoms and a deterioration of quality of life, these differences were very small when compared to the younger patients. In addition, the ELVIS study (14) showed that elderly patients receiving chemotherapy had better symptom control than did those without treatment. Thus, based on the ELVIS and our study, we might conclude that the deterioration of lung cancer symptoms occurred relatively more quickly in elderly patients receiving chemotherapy than in younger patients receiving the same; however, this deterioration was less severe and much slower than that in elderly patients who were receiving supportive care only.

The chemotherapy response rate was higher in elderly patients, or no worse than that in younger patients, in a majority of clinical studies. (6,8,9,21) There was no significant difference in survival rate with either cisplatin therapy or non-cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy in elderly patients with NSCLC compared to younger patients, although there was a trend toward poorer survival time in elderly patients in about two thirds of the studies. (6,8,9,20,21,24)

In ours and other studies, (6,9,21) cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy induced more myelosuppression in elderly patients compared to younger patients. Neurologic toxicity was even higher in elderly patients receiving paclitaxel-and-cisplatin combination therapy, because these two agents both have concomitant neurologic toxicities. (6,9) The peripheral neuropathy induced by paclitaxel treatment or the asthenia induced by docetaxel are the main issues requiring attention, because both conditions disable elderly patients easily or severely impair their daily activity. (25,26)

In conclusion, age itself should not preclude an elderly patient from receiving chemotherapy. Currently, single-agent chemotherapy and nonplatinum or platinum-based doublets can all be considered as appropriate treatment for fit elderly patients. Clinical sense, drug toxicity profiles, patient comorbidities, cost considerations, and patient preferences form the basis of our choice of which drug to use.

REFERENCES

(1) Schottenfeld D. Etiology and epidemiology of lung cancer. In: Pass HI, Mitchell JB, Johnson DH, et al. Lung cancer: principles and practice. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000, 367-388

(2) Lee-Chiong TL Jr, Matthay RA. Lung cancer in the elderly patient. Clin Chest Med 1993; 14:453-478

(3) DeMaria LC Jr, Cohen HJ. Characteristics of lung cancer in elderly patients. J Gerontol 1987; 42:540-545

(4) Extermann M. Measuring co-morbidity in older cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 2000; 36:453-471

(5) Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, et al. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:2061-2067

(6) Langer CJ, Manola J, Bernardo P, et al. Cisplatin-based therapy for elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: implications of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 5592, a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94:173-181

(7) Chen YM, Perng RP, Yang KY, et al. A multicenter phase II trial of vinorelbine plus gemcitabine in previously untreated inoperable (stage IIIB/IV) non-small-cell lung cancer. Chest 2000; 117:1583-1589

(8) Chen YM, Perng RP, Lee YC, et al. Paclitaxel plus carboplatin, compared to paclitaxel plus gemcitabine, shows equal efficacy while more cost-effectiveness: a randomized study of combination chemotherapy against inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer previously untreated. Ann Oncol 2002; 13:108-115

(9) Chen YM, Perng RP, Shih JF, et al. A randomized phase II study of weekly paclitaxel or vinorelbine in combination with cisplatin against inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer previously untreated. Br J Cancer 2004; 90:359-365

(10) Mizushima Y. Noto H, Sugiyama S, et al. Survival and prognosis after pneumonectomy for lung cancer in the elderly. Ann Thorac Surg 1997; 64:193-198

(11) Chen YM, Chao JY, Tsai CM, et al. Treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: the Chinese experience in a general teaching hospital. J Chin Med Assoc 2000; 63:459-466

(12) Gridelli C, Perrone F, Gallo C, et al. Vinorelbine is well tolerated and active in the treatment of elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a two-stage phase II study. Eur J Cancer 1997; 33:392-397

(13) Veronesi A, Crivellari D, Magri MD, et al. Vinorelbine treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer with special emphasis on elderly patients. Eur J Cancer 1996; 32:1809-1811

(14) The elderly lung cancer vinorelbine Italian study group: effects of vinorelbine on quality of life and survival of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999; 91:66-72

(15) Bianco V, Rozzi A, Tonini G, et al. Gemcitabine as single-agent chemotherapy in elderly patients with stages III-IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a phase II study. Anticancer Res 2002; 22:3053-3056

(16) Martoni A, Di Fabio F, Guaraldi M, et al. Prospective phase II study of single-agent gemcitabine in untreated elderly patients with stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 2001; 24:614-617

(17) Ricci S, Antonuzzo A, Galli L, et al. Gemcitabine monotherapy in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter phase II study. Lung Cancer 2000; 27:75-80

(18) Feliu J, Gomez LL, Madronal C, et al. Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine in non-small-cell lung carcinoma patients age 70 years or older or patients who cannot receive cisplatin. Cancer 1999; 86:1463-1469

(19) Beretta GD, Michetti G, Belometti MO, et al. Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine in elderly or unfit patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2000; 83:573-576

(20) Gridelli C, Perrone F, Gallo C, et al. Chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the Multicenter Italian Lung Cancer in the Elderly Study (MILES) phase III randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003; 95:362-372

(21) Kelly K, Giarritta S, Akerley W, et al. Should older patients (Pts) receive combination chemotherapy for advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)? An analysis of Southwest Oncology trials 9509 and 9308 [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2001; 20:a1313

(22) Kelly K, Crowley J, Bunn PA Jr, et al. Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19:3210-3218

(23) Wozniak AJ, Crowley JJ, Balcerzak SP, et al. Randomized trial comparing cisplatin with cisplatin plus vinorelbine in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16:2459-2465

(24) Shepherd FA, Abratt RP, Anderson H, et al. Gemcitabine in the treatment of elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Semin Oncol 1997; 24(suppl):550-55

(25) Fidias P, Supko JG, Martins R, et al. A phase II study of weekly paclitaxel in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2001; 7:3942-3949

(26) Hainsworth JD, Burris HA III, Litchy S, et al. Weekly docetaxel in the treatment of elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma: a Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network Phase II Trial. Cancer 2000; 89:328-333

Yuh-Min Chen, MD, PhD; Reury-Perng Perng, MD, PhD; Jen-Fu Shih, MD; Chun-Ming Tsai, MD; and Jacqueline Whang-Peng, MD

* From the Chest Department (Drs. Chen, Perng, Shih, and Tsai), Taipei Veterans General Hospital, School of Medicine, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan. and the Division of Cancer Research (Dr. Whang-Peng), National Health Research Institute, Taipei, Taiwan.

Manuscript received October 11, 2004; revision accepted December 3, 2004.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestjournal. org/misc/reprints.shtml).

Correspondence to: Yuh-Min Chen, MD, PhD, Chest Department, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, 201, Section 2, Shih-pai Rd, Taipei 112, Taiwan; e-mail: ymchen@vghtpe.gov.tw

COPYRIGHT 2005 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group