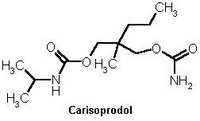

TO THE EDITOR: Carisoprodol (Soma) is an unscheduled muscle relaxant commonly used in primary care. It is metabolized to meprobamate, a schedule IV barbiturate with a long history of abuse. A small but growing amount of literature is available regarding morbidity associated with the use of carisoprodol, including respiratory compromise (1) and vehicle crashes. (2) A recent survey (3) of physicians indicates that carisoprodol's metabolism to a barbiturate is not widely appreciated, which likely contributes to its continued popularity. (3) This case report highlights this potential danger.

A 45-year-old man with grand mal seizure disorder, opiate dependence, major depressive disorder, and chronic neck and back pain presented with new-onset nocturnal "blackouts." He had no history of barbiturate abuse. He described at least three episodes during the past two weeks in which he was found wandering in his neighborhood naked. He had no memory of these events, and could only relate them based on the reports of his neighbors. Although admitting to ongoing intravenous heroin use, there was no apparent temporal link between heroin and these events. He denied recent use of alcohol or other drugs, symptoms of aura or a postictal state, recent head injury or illness, or overuse of his prescribed medications.

His medications at admission and for at least the previous month were: carisoprodol, 700 mg three times daily; gabapentin (Neurontin), 600 mg three times daily; quetiapine (Seroquel), 25 mg every night; zolpidem (Ambien), 10 mg every night; sertraline (Zoloft), 200 mg every night; and ibuprofen, 800 mg three times daily.

Physical examination showed his vital signs were within normal limits. He was alert, oriented, and scored 30 out of 30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination. Urine was only positive for opiates (routine urine drug screens do not detect meprobamate). Electrolytes, liver function tests, complete blood count, vitamin B12, folate, and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels were within normal limits. An electroencephalogram and a non-contrast head computed tomographic scan were unremarkable.

We suspected that he was experiencing amnestic periods secondary to his use of multiple psychoactive medications. Rather than discontinue carisoprodol abruptly, particularly given his seizure disorder, a pentobarbital challenge test was performed to assess his tolerance level to carisoprodol. The pentobarbital challenge test (4) involves administration of a test 200 mg dose of pentobarbital and assessment of the patient one hour later for one of four stages of barbiturate tolerance. The patient showed no symptoms of intoxication, indicating that he was at the highest stage of tolerance and, therefore, at risk of delirium, seizures, or even death with abrupt carisoprodol cessation. (5) He was placed on a one-week phenobarbital taper and was both seizure-free and without amnestic episodes during his two-week stay. He left the hospital receiving baclofen (Lioresal), 5 mg three times daily, for his back spasms; carisoprodol, gabapentin, zolpidem, and quetiapine were successfully discontinued.

This case report demonstrates clear barbiturate tolerance caused by the use of carisoprodol. The tolerance and dependence liability of carisoprodol can put patients at risk of severe withdrawal symptoms, including seizures and death. It is a curious inconsistency that carisoprodol is not scheduled, but meprobamate is schedule IV.

CRAIG HEACOCK, M.D.

MARK S. BAUER, M.D.

Department of Psychiatry

Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 116R

830 Chalkstone Ave.

Providence, RI 02908-4799

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

REFERENCES

(1.) Davis GG, Alexander CB. A review of carisoprodol deaths in Jefferson County, Alabama. South Med J 1998;91:726-30.

(2.) Logan BK, Case GA, Gordon AM. Carisoprodol, meprobamate, and driving impairment. J Forensic Sci 2000;45:619-23.

(3.) Reeves RR, Carter OS, Pinkofsky HB, Struve FA, Bennett DM. Carisoprodol (soma): abuse potential and physician unawareness. J Addict Dis 1999;18: 51-6.

(4.) Bauer MS. Field guide to psychiatric assessment and treatment. Philadelphia, Pa.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

(5.) Littrell RA, Hayes LR, Stillner V. Carisoprodol (Soma): a new and cautious perspective on an old agent. South Med J 1993;86:753-6.

COPYRIGHT 2004 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group