Objectives: The U.S. Air Force has adopted a policy "strongly discourag(ing) the use of . . . ephedra." However, the literature regarding this topic is limited and widely opinioned. In light of growing public and medical debate over the safety and efficacy of ephedrine-type alkaloid-containing dietary supplements, a review of the literature and assessment of the data were accomplished. Methods: Studies regarding Ma Huang, ephedra, ephedrine-type alkaloids, ephedrine, and dietary supplements were reviewed (from databases Medline, HealthSTAR, CINAHL, Cochrane Clinical Trials Database). Food and Drug Administration and Government Accounting Office documents (including reports and interagency communications) were reviewed. Results: Significant manufacturing quality control issues exist. Few studies support their efficacy or safety. Weight loss and athletic performance appear to be only modestly improved, for short durations, in the setting of large numbers of (some serious) adverse event reports. Studies examining overthe-counter use are minimal. Conclusions: The current U.S. Air Force policy strongly discouraging the use of ephedrinetype alkaloid-containing dietary supplements appears to be supported.

Introduction

Dietary supplements containing ephedrine-type alkaloids are widely marketed and consumed in the military. They are purchased as a means to lose weigh, to enhance mood, energy, concentration, and sexual excitement, and as legal alternatives to illegal drugs. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the dietary supplement industry, and research data are at odds regarding the safety of these products. This article will attempt to clarify this evolving issue for future Department of Defense policy making and medical practice by reviewing their history, use, pharmacology, alleged complications, safety and efficacy data, and resultant policy-making controversies.

History

Perhaps the oldest medicinal plant known, Ephedra is likely equated to "soma," a drink of immortality in the Rigveda used throughout the human life cycle.1

Ma Huang is a traditional Chinese medicine used in the third millennium BC to present day. It is derived from the aerial parts of several Ephedra species (Ephedraceae) and is used as an antitussive, antipyretic, sudorific, and anti-inflammatory agent. Ephedra altissima is one of six plants found in the grave of Shanidar IV Neanderthal (Iraq), dating back to 60,000 BC. It was likely used by early physicians to treat traumas and inflammatory injuries in the Stone Age (likely a common problem) and/or as a stimulant during exhausting hunts.2

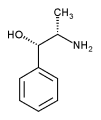

Today, ephedrine-type alkaloids from these plants, (-)-ephedrine, (+)-pseudoephedrine, H-norephedrine, (+)-norpseudoephedrine, H-N-methylephedrine, and (+)-N-methylpseudoephedrine, are marketed over-the-counter (OTC) (Ripped Fuel, Metabolife, Stacker 3, etc.) as "natural products" and "dietary supplements."3 Ephedrine-type alkaloids are usually sold as a concentrated extract; however, they can also be sold as raw botanicals or powdered plant material. Packaging is in the form of capsules, tablets, powders, and liquids. In most commercial preparations, ephedrine is the predominant sympathomimetic with most products having at least 10 mg per serving.4 Ephedrine is similar in structure and action to amphetamine. It has also been promoted as a "natural" version of the once-popular diet drug combination "fen-phen" (fenfluramine/phentermine).

Epidemiology and Scope

Dietary supplement manufacturers report selling three billion servings in 1999 alone.5 Presuming the products were consumed as directed (three doses per day for no more than 12 weeks), then approximately 12 million people used these supplements in 1999.6 The dietary supplement market has been growing at an average rate of well over one-half billion dollars per year.7

A 1996-1998 study of 14,679 noninstitutionalized adults ages 18 years and older found that 7% reported using nonprescription weight-loss products with 1% using ephedrine-type alkaloid products and 2% using phenylpropanolamine (PPA). Extrapolated to a national sample, this suggests that 2.5 million Americans are using ephedrine-type alkaloid products nationwide.8

These products have dominated Base Exchange dietary supplement shelves, even in deployed settings. A newly deployed U.S. Air Force base, 5 months after opening, had eight dietary supplements stocked and marketed for weightlifting and energy enhancement (a common pastime at such deployed sites); six contained ephedra-type alkaloids as their primary active ingredient.

According to adverse event reports (AERs) submitted to the FDA,6 59% used ephedrine-type alkaloid products for weight loss, 16% to improve athletic performance, and 6% to increase energy.

Younger adults (a majority of the active duty population) are more likely than older adults to be users of nonprescription weight-loss products.8 Although the labels of most ephedrinetype alkaloid products advise against their use by individuals less than 18 years old, among adverse events reported to the FDA involving ephedrine-type alkaloid products, 7% were under the age of 18 years; the youngest was 15 years old.6

Use of nonprescription weight-loss products is very common in young, obese women (28.4%) and is still significant in normal-weight women (7.9%).8 According to AERs, women outnumbered men by a factor of 3:2.6

Brief Review of Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetics

Ephedrine-type alkaloids are rapidly and completely absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract with an elimination half-life of approximately 3 to 5 hours. Unprocessed ephedrine and synthetic ephedrine do not appear to have significantly different absorption or disposition.9

Pharmacodynamics

Ephedrine-type alkaloids have sympathomimetic [alpha]1, [beta]1, and [beta]2 receptor agonist properties. Thus, they may constrict coronary arteries, causing vasospasm and resulting in myocardial infarction, myocarditis, and hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke.10 Thrombotic stroke may be caused by vasoconstriction of large cerebral arteries. Cardiac refractory periods may become shortened, raising the risk for dysrythmias. Hypertensive action may result in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebral vasculitis has been associated with sympathomimetics, including ephedrine.6 Ephedrine promotes bronchodilation by activating [beta]-adrenergic receptors in the lungs and is used for asthma.3 It is two and four times more potent in its bronchodilation and vasopressor effects than is pseudoephedrine.4

Psychoactive Effects, Abuse Liability

Ephedrine-type alkaloid supplements have been widely marketed as alternatives to illegal "recreational" drugs. Approximately 10% of the adverse events reported to the FDA were related to products marketed as alternatives to illicit street drugs or for euphoric purposes.4 Ephedrine-type alkaloids readily cross the blood-brain barrier and possess mild amphetamine-like central nervous system stimulation. At doses averaging 510 mg of ephedrine, psychosis may result.11 Pharmacodynamic differences among individuals may result in reactions at lower doses; especially with multicomponent ephedrine-type alkaloid-containing products. Ephedrine has been reported to cause mania4,11 and induce a subjective sense of "well-being and an elevation of mood."12 It has been suggested by one author that individuals using ephedrine-type alkaloids for asthma may "spontaneously increase the dose of the drug because of its mood-elevating effect."13 The Physicians Desk Reference for Herbal Medicines14 describes that "dependence can develop" on ephedrine-type alkaloids. Such case reports are rare,15 and psychiatric complications generally result in psychosis and affective disturbances.16 Pseudoephedrine and PPA are generally preferred for use as oral decongestants because they are less potent and less likely to cause central nervous system stimulation than ephedrine3,17 Mixtures of caffeine and (-)-methylephedrine produce stimulant effects similar to methamphetamine.18 (-)-Methylephedrine and (+)-norpseudoephedrine individually have high-abuse potential.19

Investigations of actual vs. claimed content of ephedrine-type alkaloid dietary supplements have found substantial amounts of (+)-norpseudoephedrine, a schedule IV controlled substance, normally not allowed in nonprescription medications. Known as cathine, (+)-norpseudoephedrine is associated with a substance abuse syndrome in East Africa and Arab Peninsula. The Drug Enforcement Agency has requested the FDA to restrict OTC availability of ephedrine-type alkaloid products because (1) it is known that misuse and abuse of OTC ephedrine-type alkaloid products can cause harm and because (2) they have been used as the primary precursor in the synthesis of methamphetamine and methylcathinone.4

Dietary Supplements

Traditionally, the term dietary supplement has referred to products made of one or more essential nutrients (vitamins, minerals, and proteins). The 1994 Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act broadened this definition to include, with some exceptions, any product intended for ingestion as a supplement to the diet, including vitamins, minerals, herbs, botanicals, plant-derived substances, amino acids, and concentrates, metabolites, constituents, and extracts of the these substances.7 By labeling ephedrine products as "not to be used to diagnose, cure, mitigate, treat, or prevent disease," manufacturers can avoid their products being termed "drugs" and can avoid FDA regulation. Although the FDA requires dietary supplement manufacturers to ensure their products are safe only after they are sold in stores, it does not require premarketing approval of supplement ingredients or products or labeling regarding dosing or warnings.

Ephedrine-type alkaloids are marketed in dietary supplements under at least 125 different product names with a variety of other stimulants and substances added.20'21

Medical Complications

Published case reports of complications of ephedrine-type alkaloid use include seizures,22 myocarditis,23"25 myocardial infarction,26 and possibly even acute hepatitis.27

From 1993 to 1997, the FDA received over 800 AERs (primarily cardiovascular, neurological, and psychiatric) of illnesses and injuries associated with the use of more than 100 different ephedra-type alkaloid dietary supplements. Many of these AERs occurred in young, healthy adults considered unlikely candidates for such events; 56% of these cases involved individuals less than 40 years old, 92% of these events were related to the use of products marketed for weight-loss and energy purposes, and 5% were related to products marketed for athletic-enhancement purposes. Doses as small as 8 to 9 mg per serving have been reported as causing life-threatening adverse events. Approximately 40% of reported adverse events occur within the first use or week of first use, providing little to no warning to the consumer of potential medical complications.4

Between june 1, 1997 and March 31, 1999, the FDAreceived an additional 140 AERs. The FDA requested an independent review to assess causation and to estimate the level of risk these products pose to consumers.6 Published in the New England Journal of Medicine, 31% of cases were definitely or probably related to the use of supplements containing ephedrine-type alkaloids and another 31% were possibly related, Among these events, 47% involved cardiovascular symptoms (hypertension, palpitations, tachycardia) and 18% involved the central nervous system (stroke, seizures). Moreover, 26% of the definite, probable, and possible cases resulted in permanent injury13 or death.10 Nine serious adverse events occurred in users who were taking relatively low doses of ephedrine-type alkaloids (12-36 mg/day) and who had no significant medical risk factors. The authors of the study concluded, despite some concerns otherwise,28 that dietary supplements containing ephedra-type alkaloids posed a serious health risk to some consumers and have no scientifically established benefits.

Use of nonprescription weight-loss products is far more common in physically active adults as opposed to sedentary adults.8 Ephedrine-type alkaloid users are nine times more likely to also be using prescribed medications.8 Nearly 75% of adverse events occurred in women who were using ephedrine-type alkaloid products for weight loss and who may also be using other stimulants for weight loss.4 Many users of dietary supplements fail to inform their physicians about use of these products,29 and many physicians and health care providers fail to ask. Because it is known that the rate of reporting adverse events may be less than 15%30,31 the frequency of reporting with respect to herbal products is even lower,32'33 one may estimate that the actual number of adverse events for the 22-month period is at least 933.

Common Ingredients in Ephedrine Products

A review of 125 ephedrine-type alkaloid products found that most products contained 6 to 20 other ingredients, many of which have known or suspected physiological and pharmacological activities. Selected items below are both commonly found in ephedrine-type alkaloid preparations and have clinically important interactions.4

Caffeine

Commonly included in ephedrine-type alkaloid products and commonly consumed in society, caffeine competitively inhibits adenosine-mediated dilatation of blood vessels, resulting in hypertensive vascular effects. It augments the release of catecholamines. Combining ephedrine-type alkaloids with caffeine and aspirin has been known to raise caloric expenditure rates in mammals, which is a "thermogenic effect," the safety of which is uncertain.3,34 Ephedrine-type alkaloid products have been found to contain PPA, which was previously marketed in a combination with caffeine and ephedrine (called "amphetamine look-alikes") until 1983 when the FDA banned this combination after numerous reports of adverse events. PPA and caffeine are known to have synergistic hypertensive effects and toxicity.35 Whereas the dose of ephedrine typically associated with reported adverse events is less than or equal to a typical dose used in bronchodilators (25-50 mg), the addition of synergistic substances, such as caffeine, may result in serious adverse events with ephedrine-type alkaloid products.6 A total of 70% of AERs involving ephedrine-type alkaloid products was from products labeled as containing caffeine.4

Bitter Orange (Citrus aurantium)

Common in ephedrine-type alkaloid products, this is a natural source of the adrenergic agonists synephine and octapamine. In laboratory animals, oral ingestion of C. aurantium produced dose-dependent mortality and electrocardiographic abnormalities indicative of ventricular arrhythmia.36

Salicin

Found in the botanical commonly known as willow bark, salicin reduces renal clearance of ephedrine-type alkaloids and may increase the risk of adverse events.37

Amino Acids

Commonly found in muscle-building products, high concentrations of amino acids may also reduce renal clearance of ephedrine-type alkaloids.4

Complimentary Weight-Loss Agents

Diuretics (Uva ursi-a botanical diuretic) and laxatives may be added to ephedrine-type alkaloid products to enhance weight-loss effects. However, these have been known to increase the risk of adverse events.4

FDA Regulation

Initial FDA Concerns and Actions

In 1995, the FDA issued a public warning for consumers not to consume a product containing Ma Huang and kola nut due to more than 100 reports of injuries and adverse reactions related to the product in that past year alone, including several deaths, when used at recommended doses.38 Because of the growing number and consistency of ephedrine-type alkaloid AERs (outlined above), combined with the then virtual absence of publicly available safety data, the FDA convened an ad hoc Working Group to study the issue.4 In the next 6 months, the number of ephedrine-type alkaloid AERs doubled. Highly concerned, the FDA convened its Food Advisory Committee in conjunction with the Working Group to review the situation and provide final recommendations. Specific recommendations are highlighted below. The Food Advisory Committee agreed, "the FDA should take action to address the rapidly evolving and serious public health concerns associated with the use of ephedrine-type alkaloid-containing dietary supplements."4

* Each serving is limited to

* Total serving in 24 hours must be less than 24 mg.

* The inclusion of other stimulants (caffeine, yohimbine) is prohibited.

* Labels cannot claim that long-term use is effective for weight loss or body building.

* Labels must state: "Do not use this product for more than 7 days."

* Labels of products for short-term use must warn: "Taking more than the recommended serving may result in heart attack, stroke, seizure, or death."

* Labels must caution against use by pregnant or nursing women, those with heart disease, thyroid disease, diabetes, hypertension, psychiatrie conditions, glaucoma, difficulty urinating, prostatic hypertrophy, and seizure disorders.

These rules would not apply to prescribed medications containing ephedrine.

Government Accounting Office: Data Analysis Concerns

Despite the continued flow of AERs, the FDA withdrew many of these limits in April 2000 after the General Accounting Office raised serious concerns regarding the FDAs data and interpretations. The Government Accounting Office (GAO) was tasked by the House of Representatives Committee on Science to examine (1) the scientific basis for the FDAs proposed rule and (2) the agency's adherence to the regulatory analysis requirements for federal rule making. The Small Business Administration's Office of Advocacy and the dietary supplement industry also lobbied their concerns. The GAO concluded that, although the FDA generally complied with the statutory and executive order requirements for rule making, the PDA's proposed rules above regarding placing limits on dosage and duration of use were flawed scientifically due, in part, to an inability of the FDA to require adverse event reporting on dietary supplements. The GAO concluded that, although the signs and symptoms described in the AERs were consistent with available scientific evidence and known physiological effects of ephedrine-type alkaloids, the AERs were poorly documented. Moreover, the FDA did not perform a causal analysis to determine whether ingestion of such dietary supplements caused or contributed to the adverse events.39

The GAO performed a random sample (92 of the initial 864 AERs) and found that 39% lacked information on the amount of product consumed; 41% lacked information on the frequency of consumption; 28% lacked information on the duration for which the product was consumed; 45% lacked information on dose, frequency, or duration; 24% lacked information on all three dimensions; and 62% lacked medical records, so as to ensure underlying conditions were not causative. Nevertheless, the GAO recommended further study and supported the FDAs concern as "reasonable" regarding the potential safety problems of ephedrine-type alkaloid-containing dietary supplements.39

Notably, another pharmacologically similar supplement, PPA, was curtailed by the FDA in November 2000. The FDA requested voluntary withdrawal of all OTC products (found in Dexatrim and Acutrim) due to multiple, postmarketing case reports of cerebrovascular and cardiac complications, as well as a study showing increased risk of stroke with PPA use.40,41

Recent Analyses

The ephedrine-type alkaloid content of Ma Huang varies from 0.018% to 3.4%, with ephedrine itself dominating the mix. The ephedrine-type alkaloid content of each lot harvested may vary according to geography of crop location, season of harvest, and growing conditions. There can be significant discrepancies between the ephedrine-type alkaloid potency listed on the product label vs. actual doses. For example, nine OTC dietary supplements labeled as containing ephedrine-type alkaloids were carefully analyzed with gas Chromatographie methods.3 One product contained no ephedrine-type alkaloids. Products containing measurable quantities of ephedrine-type alkaloids showed variations ranging from 0.3 mg/g to 56 mg/g. Another study found ephedrine-type alkaloid content to vary by as much as a factor of five between different products with one product having a lotto-lot variation above 130%.42 A similar study18 found variations in (-)-methylephedrine content in excess of 1,000% and differences in (-)-ephedrine content exceeding 260%. Over one-half of the dietary supplement products studied either failed to make a label claim for alkaloid content or exceeded 20% difference between alkaloid content vs. label claim. In general, most ephedrine-type alkaloid products, regardless of their promoted use, have ephedrine-type alkaloid levels at or above 10 mg per serving.4

Currently, there are no FDA-regulated medications that contain multiple ephedrine-type alkaloids due to potential for additive or synergistic sympathomimetic effects and toxicities. However, this concern is not applied to dietary supplements.19

The Council for Responsible Nutrition, a consortium of major nutritional companies founded in 1973, asked Cantox Health Sciences International, a respected independent scientific consulting firm, to evaluate ephedrine-type alkaloid's safety. Cantox found ephedrine-type alkaloids safe at a daily dosage of 90 mg per day (divided into 30-mg doses), provided effective labeling, and postmarket monitoring was implemented. These findings were anchored by a recent 6-month prospective, two-arm, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled safety and efficacy trial of a 90-mg ephedrine-type alkaloid, 192-mg caffeine product used in overweight but otherwise healthy subjects who were also enrolled in a protocol invoking healthy diet and exercise. The study excluded individuals noncompliant with the protocol and those with general health problems (including hypertension, significant ventricular ectopy, significant cardiac diseases). The study group experienced small persistent increases in heart rate and blood pressure and significant beneficial effects in body weight, body fat, and blood lipids.43 The authors discussed similar previous results from at least two other clinical trials with herbal ephedra and four trials with synthetic ephedrine.

However, a recent database review of the FDA's Adverse Reaction Monitoring System (including clinical records, investigative reports, and autopsies) continues to raise concern. Of 929 cases of possible Ma Huang toxicity reported to the FDA from 1995 to 1997, 37 well-documented cases involved serious cardiovascular events. A review of these cases led the authors to conclude: (1) Ma Huang use is temporally related to stroke, myocardial infarction, and sudden death; (2) underlying heart or vascular disease is not a prerequisite for Ma Huang-related adverse events; and (3) the cardiovascular toxic effects associated with Ma Huang were not limited to massive doses.44

Both the National Football League and the National Collegiate Athletic Association have adopted policies and programs to prohibit the use of ephedrine-type alkaloids in their athletes.44 The National Institutes of Health guidelines on obesity management state that herbal preparations are not recommended as part of a weight-loss program.45 Moreover, the U.S. Air Force, after experiencing a trend of deaths in fairly young, healthy, active duty troops believed to be related to the use of ephedrine-type alkaloid-containing dietary supplements, has recently adopted a policy "strongly discouragfing) the use of nutritional supplements containing ephedra by all U.S. Air Force personnel as an operational risk management posture."46 Since this policy, the Rand Corporation released a pivotal study supporting only modest, short-term weight-loss and athletic-enhancing effects. Little evidence was available regarding OTC safety and efficacy. These products were associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal, psychiatric, and autonomie complications. A hypothesis testing study was deemed indicated due to concern for the significant number of potentially life-threatening events.47

Discussion

The FDA's regulatory powers over marketed dietary supplements are significantly less than with food additives or drugs.7 Twenty-one states have passed regulations stricter than federal regulations, including requiring that ephedrine-type alkaloid products be made available by prescription only, scheduling the substance, and prohibiting weight loss, appetite control, or stimulant claims on the labels.48

A survey of 238 herbal product manufacturing companies revealed that only 70% had written procedures for the production process and only 60% performed testing of ingredients or finished product to ensure quality.49'50

The increasingly publicized safety problems associated with ephedrine-type alkaloid dietary supplements may only be an artifact of the PDA's passive AER system. While the Boozer et al.43 study did find ephedrine-type alkaloids safe at a total daily dose of 90 mg or less, the FDA has recently tested 25 different ephedrine-type alkaloid products from the marketplace over a 2-year period and found individual doses/pills to range as high as 110 mg.39

The use of these supplements by soldiers (who are often engaged in sports, military physical conditioning programs, deployments to arid locations, and the use of muscle-bulking supplements) is an added concern. Data from the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research50 indicate that, during the past three decades, three possible periods of heatstroke fatality trends in American football are evident (Fig. 1).

The period of 1959-1974 predated the awareness of the dangers of dehydration in sports. The period of 1975-1984 began with publication of scientific reports regarding this issue and the advantages of proper hydration before, during, and after practices and games. Fatalities dropped from 4.4/year to 1.7/ year. The period of 1985-1994 revealed only 0.6 deaths/year. However, recently (1995-2001), this downward trend has reversed in the context of significant increases in dietary supplement use, specifically ephedrine-type alkaloid dietary supplements.52 Public awareness regarding this subject (and that of athletic teams/trainers) was greatly improved after the wellpublicized and unfortunate football practice-related deaths in the summer of 2001.

Obesity is a tragic public health problem, and these products may have a place within a structured, medically supervised civilian weight management program. However, unsupervised OTC civilian use in the context of aggressive marketing tactics (including paid testimonials and product endorsements by physicians supporting the safety and efficacy of these supplements)52 is a matter of concern. The FDA has identified a profile for individuals who may be at higher risk for sensitivity to sympathomimetic agents (Table I).4

Conclusion

Specific concerns regarding ephedrine-type alkaloid-containing dietary supplements include:4,19

1. A large yet uncertain set of data suggesting, but clearly not proving, a causal association between the use of ephedrine-type alkaloids and subsequent adverse events,

2. The presence of multiple alkaloids per product resulting in a variety of alkaloid potencies and actions,

3. The presence of other stimulants that may cause additive or synergistic sympathomimetic effects,

4. Frequent and alarming differences between label vs. actual ephedrine-type alkaloid content,

5. Dramatic variances in alkaloid content within and among specific products, and

6. Potential medical, psychiatric, and psychoactive abuse complications of such products.

Currently, the FDA is unifying its reporting system to better track and analyze reports. Expansion of the FDA's involvement of premarket testing, safety, and labeling issues involving dietary supplements may be a future consideration, as may be a more active AER reporting system. Still, consumers are known to often take OTC products in greater dosages and for longer durations than directed on the product label.54

Evidence supporting the benefits vs. risks of closely supervised administration of ephedrine-type alkaloid products along with medical monitoring for a fairly healthy subpopulation compliant with product labeling and concurrent psychosocial interventions is present for the treatment of obesity. However, their well known, unsupervised use by soldiers subjected to the demands of excessive athletic training, rigid weight standards, and arid deployments is largely unstudied. U.S. Air Force policy on this issue is likely warranted.

References

1. Mahdihassan S, Mehdi FS: Sonia of the Rigveda and an attempt to identify it. Am J ChinMed 1989; 17: 1-8.

2. Lietava J: Medicinal plants in a Middle Paleolithic grave Shanidar IV? J ELhnopharmacol 1992: 35: 263-6.

3. Betz JM, Gay ML, Mossoba MM, Adams S: Chiral gas Chromatographie determination of ephedrine-type alkaloids in dietary supplements containing Ma Huang. J AOAC Int 1997; 80: 303-15.

4. Dietary Supplements Containing Ephedrine Alkaloids; Proposed Rule. Federal Register. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, 21 CFR, Part III, Rockville, MD, 1997; 62: 30677-724.

5. Dietary Supplement Market View. Chevy Chase, MD, FDC Reports, August 2000.

6. Haller CA, Benowitx NL: Adverse cardiovascular and central nervous system events associated with dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids. N Engl J Mccl 2000; 343: 1833-8.

7. Kurtzwell P. An FDAguide to dietaiy supplements. FDA Consumer 1999 January. Food and Drug Administration. Available at http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/ fdsupp.html; accessed November 14, 2002.

8. Blanck HM, Khan LK, Serdula MK: Use of nonprescription weight-loss products: results from a multistate survey. JAMA 2001; 286: 930-5.

8. Gurley BJ, Gardner SF, White LM, Wang PL: Ephedrine pharmacokinetics after the ingestion of nutritional supplements containing Ephedra sinica (Ma Huang). Ther Drug Monil 1998; 20: 439-45.

10. Bruno A. Nolte KB, Chapin J: Stroke associated with cphedrine use. Neurology 1993; 43: 1313-6.

11. Capwell RR: Ephedrine-induced mania from an herbal diet supplement (letter). AmJ Psychiatry 1995; 152: 647.

12. Whitehouse A, Duncan J: Ephedrine psychosis rediscovered. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 150: 258-61.

13. Martin W, Sloan J, Sapira J, Jasinski D: Physiologic, subjective, and behavioral effects of amphetamine, methamphetamine, ephedrine, phenmetrazine, and methylphenidate in man. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1971; 12: 245-58.

14. Fleming T (editor): Physicians Desk Reference for Herbal Medicines, Ed 2. p 489. Montvale, NJ, Medical Economics Company, 2000.

15. Miller SC, Waite C. Ephedrine-type alkaloid containing dietary supplements and substance dependence. Psychosomatics 2003; 44:508-11.

16. Jacobs KM, Hirsch KA: Psychiatric complications of Ma Huang. Psychosomatics 2000:41:58-62.

17. Harvey SC: In Remington's Pharmaceutical Sciences, Ed 18, pp 870-5,878, 884. Edited by Gennaro AR, Chase GD, Der Marderosian A, et al. Easton, PA, Mack Publishing Company, 1990,

18. Gurley EiJ, Gardner SF, Hubbard MA: Content versus label claims in ephedracontaining dietary supplements. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2000; 57: 963-9.

19. Keup W: Use, indications and distribution in different countries of the stimulant and hallucinogenic amphetamine derivatives under consideration by WHO. Drug Alcohol Depend 1986; 17: 169-92.

20. Carey B: Risks of ephedra usage in spotlight. The Los Angeles Times. August 27, 2001, p DIl, D13.

21. Ros JJW, Pelders MG, DeSmet PAGM: A case of positive doping associated with a botanical food supplement. Pharm World Sei 1999; 21: 44-6.

22. Kockler DR, McCarthy MW, Lawson CL: Seizure activity and unresponsiveness after hydroxycut ingestion. Pharmacotherapy 2001; 21: 647-51.

23. Zaaks SM, Klein L, Tan CD, Rodriguez ER, Leikin JB: Hypersensitivity myocarditis associated with ephedra use. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 1999; 37: 485-9.

24. Leikin JB, Klein L: Ephedra causes myocarditis. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2000; 38: 353-4.

25. Kurt TL: Hypersensitivity myocarditis with ephedra use. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2000; 38: 351.

26. Traub SJ, Hoyeck W, Hoffman RS: Dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids (letter). N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1096.

27. Nadir A, Agrawal S, King PD, Marshall JB: Acute hepatitis associated with the use of a Chinese herbal product, Ma Huang. Am J Gasiroenterol 1996; 91: 1436-8.

28. Hutchens GM: Dietaiy supplements containing ephedra alkaloids. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1095-6.

29. Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al: Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997. JAMA 1998; 280: 1569-75.

30. Chyka PA, McCommon SW: Reporting of adverse drug reactions by poison control centres in the U.S. Drug Saf 2000; 23: 87-93.

31. Spontaneous adverse event reports. Available at http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/ dockets/ac/99/slides/3558sle/lsld003.htm; accessed july 15, 2002.

32. Dietary Supplements Containing Ephedrine Alkaloids. FDA docket no. OON1200. Rockville, MD, Food and Drug Administration, 2000. Available at http:// www. accessdata. fda. gov/scripts/oc/ohrms/index. dm; accessed july 10, 2002.

33. Barnes J, Mills SY, Abbot NC, Willoughby M, Ernst E: Different standards for reporting ADRs to herbal remedies and conventional OTC medicines: face-to-face interviews with 515 users of herbal remedies. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 45: 496-500.

34. Bray GA: Use and abuse of appetite-suppressant drugs in the treatment of obesity. Ann InI Med 1993; 119: 707-13.

35. Brown NJ, Ryder D, Branch RA: A pharmacodynamic interaction between caffeine and phenylpropanolamine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1991; 50: 363-71.

36. Calapai G, Firenzuoli F, Saitta A, et al: Antiobesity and cardiovascular toxic effects of Ciirus auranlium extracts in the rat: a preliminary report. Fitoterapia 1999; 70: 586-92.

37. Tatro DS, Olin BR (eds): Salicylates: salicylic acid derivatives: drug interaction facts. St. Louis, MO. Facts and Comparisons. 1996, pp 248a-d.

38. Stone B: FDA warns consumers against Nature's Nutrition Formula One. HHS News. Rockville, MD, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, February 28, 1995. Available at http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~lrd/forml.html; accessed November 14, 2002.

39. Dietary supplements: uncertainties in analyses underlying FDA's proposed rule on ephedrine alkaloids. Report to the Chairman and Ranking Minority Member, Committee on Science, House of Representatives. GAO/HEHS/GGD-99-90. Washington, DC, U.S. General Accounting Office, july 1999.

40. Food and Drug Administration: Dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids, withdrawn in part. Federal Register 2000; 65: 17477.

41. Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Brass LM, et al: Phenylpropanolamine and the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 1826-32.

42. Gurley BJ, Wang P, Gardner SF: Ephedrine alkaloid content of five commercially available herbal products containing Ephedra sinica (Ma Huang). Pharm Res 1997; 14: S582-3.

43. Boozer CN, et al: Herbal ephedra/caffeine for weight loss: a 6-month randomized safety and efficacy trial. Int J Obes 2002; 26: 593-604.

44. Samenuk D, et al: Adverse cardiovascular events temporally associated with Ma Huang, an herbal source of ephedrine. Mayo Clin Proc 2002; 77: 12-6.

45. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. Obes Res 1998; 6(Suppl 2): 51S-209S.

46. Carlton PK: USAF policy on the use of ephedra (Ma Huang) containing nutritional supplements [memorandum]. Washington, DC, Office of the Surgeon General, Headquarters, United States Air Force, September 5, 2002.

47. Shekelle P, Morton S, Maglione M, et al: Ephedra and ephedrine for weight loss and athletic performance enhancement: clinical efficacy and side effects. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 76 (Prepared by Southern California Evidence-Based Practice Center, RAND, under Contract No. 290-97-0001, Task Order No. 9). AHRQ Publication No. 03-E022. Rockville, MD, Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, February 2003.

48. Coleman E: Ephedrine: Health Care Reality Check Frequently Asked Questions Sheet. Available at http://www.hcrc.org/faqs/ephedrine.html; accessed December 5, 2001.

49. Dickinson A: Good manufacturing practices for dietary supplements: a necessary step toward assuring product quality. Update: food and drug law, regulation, and education. Washington, DC, Food and Drug Law Institute, june 12-15, 2000.

50. National Nutritional Foods Association: Available at http://www.nnfa.org/ quality/GMPs.html; accessed September 27, 1999.

51. Mueller FO. Cantu RC: Annual survey of football injury research, 1931-2001: heatstroke fatalities 1931-2001. National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research. Available at http://www.unc.edu/depts/nccsi/FootballInjuryData. htm#TABLE%208; accessed October 31, 2002.

52. Bailes JE, Cantu RC, Day AL: The neurosurgeon in sport: awareness of the risks of heatstroke and dietary supplements. Ncurosurgery 2002; 51: 283-6.

53. Hydroxycul Periodical Advertisement. MuscleTech R&D, Inc, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada, October 2002.

54. Jones WK: Safety of dietary supplements containing ephedrine alkaloids. Public Meeting/Report. FDA, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, August 2000. Available at http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/ds-ephe3.html; accessed November 14, 2002.

Guarantor: Lt Col (s) Shannon Corey Miller, USAF MC

Contributor: Lt Col (s) Shannon Corey Miller, USAF MC

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, 74MDOS/SGOHE, 4881 Sugar Maple Drive, Wright Patterson Air Force Base, Wright State University, Dayton, OH 45433.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

This manuscript was received for review in January 2003. The revised manuscript was accepted for publication in May 2003.

Reprint & Copyright © by Association of Military Surgeons of U.S., 2004.

Copyright Association of Military Surgeons of the United States Feb 2004

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved