Chewing the Q'at

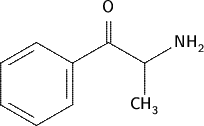

At 5 p.m. I arrive at the home of All Saif, a former member of Parliament, on a quiet side street in Sana'a, the capital of Yemen. It is a Monday in late August, and this is the weekly gathering of opposition journalists. Outside the mafraj, or sitting room, is a massive pile of sandals; inside, cushions line the walls and a thin plastic sheet - littered with the waxy green leaves and branches of discarded q'at - covers the floor. Q'at is a shrub cultivated by farmers in Yemen's fertile mountains. Its twigs, stems, and shoots are chewed like tobacco, releasing a stimulant, cathinone, which produces an amphetaminelike buzz. Q'at is illegal in the U.S. but it is Yemen's social lubricant of choice. No midafternoon conversation would be complete without it.

About thirty men, mostly middle-aged, many wearing a traditional white robe and jambiya - the curved dagger tucked into a thick, embroidered belt - are seated on the cushions. They talk, read newspapers, smoke cigarettes, and tend to text messages. A small fan wheezes away.

Opposition journalists are a rare breed in this poor nation of twenty million. They are a disparate group - socialists, communists, Arab nationalists, and Islamists with little in common beyond a sharp tongue for the current regime. Many have been punished for things they have written. At AIi Saif s salon, persecuted journalists not only get commiseration, they also devise ways - however quixotic - to fight back.

The question before the group today is how to help the editors at the weekly al shours. In August, the government threatened to shut down al Shoura and jail its editor, Abdull Kareem Al-Khaiwani, for criticizing the government's handling of a standoff between the military and a rebel cleric. The confrontation turned into a bloody siege that dragged on for the entire summer, ending only after the cleric had been killed.

The official explanation, parroted on state TV and in the larger papers, was that the cleric - who railed against the corrupting influence of the West - was a terrorist. al shoira, though, spanked the government for being ill prepared to take on the cleric, for killing civilians while waging its military campaign against him, and for sowing the seeds of terrorism. In August, Al shoura was charged with slander. The judge declined al Showra's request to present a defense.

As Al-Khaiwani talked, the rest of us sat, listened, and, of course, chewed. I'or me, q'at had the effect of a strong cup of coffee. My grasp of Arabic is limited, but following the conversation Necame easier the longer I chewed.

After two hours, AIi Saif wrapped up the meeting and circulated a petition, calling for the government to drop its case against ali Shoura. Despite their efforts, in early September, a judge closed al sahoura for six months and sentenced Al-Khaiwani to serve a year in Sana'a's Central Prison.

In November, after reports surfaced that Al-Khaiwani had his jaw broken by another inmate, dozens of journalists demanded to see their colleague. Their request was denied. There would 1% more to discuss at All's.

Geoffrey Craig is a graduate student in international affairs at Columbia University.

Copyright Columbia University, Graduate School of Journalism Jan/Feb 2005

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved