The piles of khat at Parcharafi market were of prime quality, a luminous dark green, glistening in their wrappings of banana leaves. The muzzein's afternoon call to prayer had come and gone and a queue of buyers was forming to start the long, langorous hours of hallucinogenic chewing.

In Hargeisa, the capital of a country ostracised by the rest of the world, khat is among the very few pleasures left for the vast mass of the dispossessed. Even the fortunate few who are in work rush to get their fix. What passes for business life is over by mid- day, with clusters of men squatting on the floors in tin shacks beside the dusty, pot-holed streets, rolling wads of the leaves in their mouths.

A few days ago, officials in Somaliland launched an initiative to try to regulate the sale and consumption of khat, one of the last chances the country has, they say, of pulling back from the abyss before turning into a fully fledged narco-economy.

The mayor of Hargeisa, Hussein Mohamud Jiir, has set aside tracts of land on the outskirts of the capital where sellers of the drug can be installed and monitored. Abdulkarim Adan Omar, the development director at the environmental ministry, declared that as well as fracturing Somaliland's social and commercial structure, khat was also causing huge damage to nature. 'Young people in rural areas are burning charcoal to buy khat. Their common saying is, 'Cut a tree to chew a twig'.' But the dealers in the dusty streets of Hargeisa protest that they are providing a valuable service.

Ali Omar, whose stall is near the government offices in the centre of Hargeisa, shrugged. 'It is a silly question to ask why I sell khat. Can you just go to the store across the road and ask why he is selling food? People need us.'

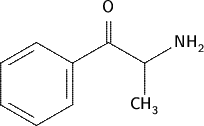

The plant, which contains a natural amphetamine, is a main source of revenue for the government, which sells licences to those involved in the business. It is also a valuable export crop, with Britain a prime destination.

The price of khat in Somaliland reflects the poverty of the country, a former British protectorate and now one of the poorest countries in the world, internationally unrecognised and starved of aid 14 years after seceding from neighbouring Somalia.

The drug sells for 50p a bunch here. But the real money for those dealing in the potent leaves is in the West, with the same amount fetching pounds 5 in the streets of Britain, where it is legal, and 10 times more in the United States, where it is not. Regular flights leave from the Horn of Africa to Liverpool, Birmingham and London packed with khat leaves. Seven tons arrive at Heathrow, perfectly legally, every week.

But the sheer amount of revenue, estimated at pounds 150m a year, has attracted the involvement of organised crime, police and customs say. Kenneth Noye, the notorious gangster, was said to be considering investing pounds 500,000 in the trade before his conviction for murder at the Old Bailey.

There are also reports that proceeds from the trade are being used to subsidise terrorism. Osama bin Laden was based in Somalia before moving to Taliban-run Afghanistan, and the July 21 London bombings, with suspects from Somalia and Eritrea now under arrest, point at links between the Horn and Islamist militancy.

Robert Emerson, a security analyst, said: 'It is a simple and effective way for groups, be they purely criminal or political, to raise money with very little risk, after all the product is not even illegal in this country and there are well-established trade routes.' The underworld uses Britain as a staging post for other countries where khat is banned including many states in Europe as well as North America. But there is also a large customer base in the UK among the Somali and Ethiopian communities and a growing market among other ethnic groups.

Two psychiatrists, Dr Mansfield Mela and Dr Andrew McBride, carried out a survey in south Wales, which has a large Somali population. They found 72 per cent of Somalis questioned said they had used khat at some time and 46 per cent said they had done so in the previous week.

Abdulkarim Adan, the director of the Somali Progressive Association in Cardiff, said: 'I chew khat on the weekends with my friends. It is a cultural and social thing, a bit like going down the pub. And it is like anything; if you use too much, there are going to be problems. It's the same as alcohol; if you abuse it, you are going to get problems. A lot of people I know have given it up because of the health risks.'

Abdi Jama, a youth worker from Newport, added: 'Lots of the teenage boys are taking it up and it has a real effect on them; this is very worrying.'

Studies had been made of the risks posed by the leaves, also known as African salad, whose main ingredient is the chemical cathinone, the equivalent of a class A drug in the US. Users of khat describe symptoms ranging from hyper-activity to aggression followed by tremendous 'downs' of depression and lethargy.

Professor Peter Haughton, of King's College London, said: 'Clinicians who work with patients who chew khat regularly, certainly in this country, pick up that quite a few have psychological problems.' In other countries, 'there seems to be a high incidence of strokes and heart attacks. The effects on the heart and bladder can be explained by what's known about the pharmocological properties of some chemicals in khat'.

The Home Office says there are 'no immediate plans to control khat or ban it under the Misuse of Drugs Act', with the rider that the situation is being kept under continuous review and further research is being done.

But studies at King's College also showed that cathinone in khat produced a chemical which could boost the power of men's sperm, and help infertile couples. Lynn Fraser, professor of reproductive biology, said: 'It might be relatively easy to develop products. And the amount that's required isn't that high, so it's not a question of taking very high doses and becoming overstimulated.'

The debate in the West about khat is academic in Somaliland. Its main export, livestock, has suffered a crippling blow after the biggest customer, Saudi Arabia, imposed an embargo, saying Somali cattle suffered from Rift Valley fever. The Somaliland government says this is a political decision taken under pressure from other Arab and African countries determined that a breakaway state should not be allowed to prosper and become an example to their own disaffected regions.

Khat is now one of the chief money-earning export crops. But it is also hugely in demand at home. Hundreds of khat chewers marched in protest in Somaliland when the price of the leaves doubled recently. There were similar protests in Somalia when Kenya temporarily banned khat flights to Mogadishu as an 'anti-terrorist measure'.

Officials in Somaliland are deeply worried by khat dependence among the young. Abdurrahman Mohammed Mal, the director general at the education ministry, said: 'You see boys no more than 13 starting on khat. They then drop out of the education system and get involved in all kinds of things to feed their habit. It is a bad, bad thing.'

Abebaw Zeleke, the programme manager for Save the Children UK in Somaliland, said: 'The hopelessness of the economic situation adds to the problem. But it is not just the younger generation being affected. Most office work stops after lunchtime because of khat- chewing. It is deeply ingrained in Somali life.'

Buying his khat, Sher Hassan Abdulrahim claimed it was his consumption of the drug for more than 40 years which has equipped him to continue his construction business at 66. 'It gives you energy, it keeps you going; the light is always on,' he said with a chortle. Mr Abdulrahim, who served with the British Army during the Aden emergency, added: 'It gives you energy and keeps you young. It is better than smoking tobacco.'

But Mr Abdulrahim's children have eschewed chewing. 'All 16 of them. They all live in England, and none of them chew.' He shook his head with regret. 'Most of them are graduates, they are in professional jobs, and they think it is old-fashioned. I know it is still very popular in Britain among Somalis, but the more educated they become the less they want khat.'

Hamid Abdullah Hassan says he is 16 but looks a lot younger. Munching his khat, he is defiant. 'Why shouldn't I take it? If there was any chance of a job then I will stop. But there is no chance and there is nothing else to do.'

What about sperm strengthening tendencies of khat? The mere mention of this makes Majida Ali Abbas and her friends hoot with laughter at the coffee shop of the Al-Mansoor Hotel. 'The men have a strange way of showing it, if that is the case. All they do is chew khat and spend seven, eight hours in the company of other men jabbering. It is very much a world of men, everyone involved in it are men.'

Ginao Mhabi, 30, selling khat at the market, is one of the exceptions. 'I am not doing this out of choice as a woman. But my parents are old and I have 10 brothers and sisters to support. The men who could have earned money for the family were all killed in the civil war. But it is not easy being a woman in this job. The men are addicted; they will come and demand you give them khat even when they do not have the money. They insult you and rob you. If I could find something else to do, then I would. I do not make much money out of it.'

Ahmed Daoud Juma is someone who does make money out of khat, and does not apologise. His family farm in Gabiley, west of Hargeisa, is covered with acres of swaying, 5ft-high khat shrubs. 'What else can we grow? The government has given us nothing to replace it with. Anyway, khat is legal, not just in this country, but England as well. It is not like heroin and cocaine.

'The Ethiopians sell it and we must as well. Some people in the West are complaining about it because Africans are making money out of it, but the money the dealers are making in England and America is far more than we do. But that is not a surprise, that is always the way among white and black people.'

But the cousins Usman Mohammed and Ahmed Awali, who have a 20- acre khat farm, say they would change to another crop, given the chance. 'We are not the ones making the money from this,' said Mr Mohammed, 35. 'We would earn much more if we could plant fruit trees, but we haven't got the money for the irrigation that needs. We also know khat is damaging the health of people who take it and that includes us. It stops people from working properly and that is not good for the country.'

Copyright 2005 Independent Newspapers UK Limited

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved.