* The Case

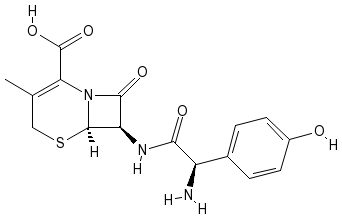

A 17-year-old male Caucasian presented with a rash confined to his lower extremities, but no other symptoms. He first noticed the rash several weeks prior to the office visit. The lesions were erythematous papules that surrounded the hair follicles without any particular distribution pattern. The rash was diagnosed as folliculitis and treated with cefadroxil (Duricef); however, soon after treatment initiation, generalized urticaria developed and the antibiotics were discontinued.

The rash persisted for several weeks and the lesions changed in appearance from petechiae to purpura, and then faded to reddish-brown lesions. The patient began to experience mild fatigue and hematuria. His urine was dark brown, progressing to medium brown. In the midst of the rash, the patient was treated with amoxicillin and potassium clavulanate (Augmentin) for sinusitis with occasional epistaxis.

History

The patient's history was otherwise unremarkable. He denied recent febrile illness, streptococcal infection, arthralgia, myalgia, and abdominal pain. His extremities showed no edema, and he denied hematemesis, hemoptysis, or hematochezia. He had no known drug allergies, but he had a history of urticarial reaction to bee stings and strawberries. His immunizations were current. He denied tobacco, alcohol, and drug use. His family history was positive for rheumatoid arthritis in extended family members.

Physical Examination

The physical examination revealed an alert adolescent who did not appear to be in acute distress. His vital signs were normal except for an elevated blood pressure of 132/76 mm Hg. The examination yielded normal findings except for diffuse reddish-brown lesions on the lower extremities.

Laboratory test results included a normal complete blood count (CBC) and platelet count with a white blood cell count of 8,200. The sedimentation rate was elevated at 35 mm/hour. Hemoglobin was normal at 14.4 grams/dl. Hepatitis C antibody was negative and the antinuclear antibody was negative. There was a prolonged bleeding time with an international normalized ratio of 1.1. His thyroid-- stimulating hormone level was within normal limits and his cholesterol was 206 with a high-density lipoprotein level of 81. Urinalysis findings included 2+ protein, 50 to 100 red cells, and 2 to 5 white cells. The 24-hour urine test showed 4.7 grams of protein with a creatinine clearance of 108. Serum creatinine was 1.7 (see Table).

Differential Diagnosis

Prior to laboratory testing, the differential diagnosis included septicemia, meningitis, leukemia, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), cutaneous drug eruption, erythema multiforme, rickettsial infection, and viral exanthem.1 With any petechial rash, sepsis and meningitis must be ruled out. A normal white blood cell count and differential eliminated both of these possibilities. Furthermore, the patient was afebrile, did not exhibit meningeal signs, and otherwise appeared healthy. Because of his normal CBC and platelet count, leukemia and ITP were ruled out.

Because of the patient's urticarial reaction to the antibiotic and general allergy history, cutaneous drug reactions were also considered. Although the rash was present prior to antibiotic therapy, the treatment seemed to exacerbate symptoms; however, this type of rash is not characteristic of drug reactions. Skin rashes that appear after antibiotic therapy usually appear on the trunk initially and have a maculopapular or morbilliform appearance. The exanthem usually appears after 1 to 3 weeks of treatment and may last up to 6 weeks after the drug is stopped.2

Erythema multiforme (EM) was also considered in the differential diagnosis. EM has been linked to preceding viral or bacterial infections and exposure to various foods, drugs, and immunizations. EM lesions are pink papules that often change color and are in an acral distribution. EM lesions appear on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, resembling target lesions. Affected patients may have mild malaise and a low-- grade fever prior to rash onset. The lesions resolve spontaneously in 1 to 3 weeks.3 The patient's symptoms were not consistent with EM.

Tick-borne infection was considered because the patient lived in a deer tick endemic area;4 however, patients with tick-borne infections are generally ill-appearing and have flu-like symptoms.5 The patient had no known tick bites and laboratory results ruled out rickettsial disease.

Viral exanthems are usually maculopapular eruptions that may accompany a febrile illness. The etiology includes human parvovirus B-19, rubeola, rubella, adenoviral, and enteroviral infections.1 The patient's rash and other associated symptoms were not characteristic of a viral exanthem. Diagnosis Based on the physical findings, the patient was diagnosed with Henoch-- Schoenlein purpura (HSP). Both the purpuric lesions to the lower extremities and the presence of hematuria were diagnostic. Treatment The patient was treated with a short course of prednisone 20 mg q.i.d. at the onset of the rash. Once he was diagnosed with HSP, prednisone therapy was gradually tapered off. Hydroxyzine (Atarax) 1 teaspoon at night and certirizine (Zyrtec) 10 mg daily was prescribed to prevent rash recurrence. The patient's hypertension was treated with amlodipine besylate (Norvasc) 25 mg. His follow-up consisted of a urinalysis every other week, monthly creatinine levels, and careful blood pressure monitoring. The continued presence of hematuria and proteinuria were still a concern 4 months after his diagnosis, but these conditions gradually resolved over the next 12 months. Discussion HSP, also known as anaphylactoid purpura, is a childhood disorder characterized by inflammation and IgA-- mediated hypersensitivity vasculitis. The vasculitis affects the small blood vessels that perfuse the skin, joints, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract. The classic symptoms include abdominal pain, nephritis, arthralgia/arthritis, and a purpuric, petechial rash.6 All of these symptoms, however, are not always present. For example, some patients will present only with nonspecific abdominal pain.' Lowgrade fever and malaise occur in approximately 50% of children.

The etiology of HSP is unknown, but a previous streptococcal infection, upper respiratory infection, or recent episode of gastroenteritis may be involved.1,6 HSP occurs predominantly in the winter and fall and affects males twice as often as females. Most cases are reported in children ages 2 to 8. Systemic complications may include central nervous system (CNS), gastrointestinal, and renal involvement. CNS manifestations are uncommon, but may include seizures, paresis, and coma.6

Cutaneous manifestations of HSP include urticarial wheals, erythematous maculopapules, or ecchymotic lesions typical of petechiae or purpura. Regardless of the rash's initial presentation, it eventually becomes petechial or purpuric in appearance. The rash occurs in crops in a symmetric pattern. It is confined predominantly to the lower extremities and buttocks; however, it may involve the trunk, face, and upper extremities. The rash is usually the most overt illness symptom. Initial lesions may blanch with pressure while late-stage lesions may not. Purpura may change in color from red to purple then rust, and eventually fade. Because of the rash's various stages, it may appear polymorphorous or be confused with urticaria. Although useful for diagnostic purposes, the rash does not cause longterm complications.',

Joint and gastrointestinal involvement occurs in approximately 66% of children with HSP. Arthralgia characteristic of HSP generally includes the large joints of the knees and ankles. Arthralgia presentation is typical of arthritis with corresponding warmth, tenderness, and inflammation of the affected area. Fluid accumulation at the involved joint may be present, and edema to the extremities and dependent areas may also occur. The arthritis is usually transient, lasting only a few days, and without longterm sequelae.36

Abdominal pain associated with HSP is described as colicky with possible hematemesis. Frank or occult blood in stools may occur. Careful abdominal assessment may reveal distension, abnormal bowel sounds, and rebound tenderness. The pain is nonradiating and is generally in the periumbilical region. Abdominal pain may be a secondary result of the vasculitis that causes bleeding into the intestinal mucosa. Gastrointestinal involvement may progress to intussusception, gastrointestinal bleeding, and shock. Other rare complications include bowel infarction and intestinal perforation."

Renal involvement, one of the most serious complications of HSP, is usually manifested by microscopic hematuria. Gross hematuria, proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, and glomerulonephritis are also possible. Nephritis occurs predominantly in the adolescent population and is usually noted within 3 months of rash onset.3 The presence of melena and a prolonged rash increases the patient's risk for nephropathy. Proteinuria and hematuria occurring simultaneously are indicative of potential renal insufficiency. 9

Hypertension is a significant complication. In the presence of HSP, hypertension alone is indicative of renal involvement and is the result of renal vascular inflammation.9 Renal disease associated with HSP occurs in 20% to 50% of cases. End-stage renal disease occurs in a relatively low percentage of affected children.'

In addition to the usual symptomatology, laboratory testing assists in the diagnosis of HSP. Although a definitive HSP test does not exist, an elevated serum IgA is often indicative. Other suggestive laboratory data include an elevated or normal CBC with possible eosinophilia. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate may also be elevated, indicating an inflammatory response. Platelet counts are generally elevated or within normal limits, differentiating HSP from ITP Coagulation studies are within normal limits. A negative antinuclear antibody rules out autoimmune diseases. A skin biopsy of the purpuric lesions may reveal leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Depending on the extent of gastrointestinal involvement, serum electrolytes may be altered. Urinalysis may reveal hematuria and proteinuria of varying degrees.',

In more progressive phases of renal involvement, elevated blood-urea nitrogen and creatinine, decreased glomerular filtration rate, and hypertension may occur (see Table).', Prognosis The prognosis for patients with uncomplicated HSP is excellent, although it recurs in approximately 50% of patients. In children younger than age 2, the illness is less severe and has a short duration with few complications.'

Patients with renal involvement can also expect to completely recover. Less than 1% of patients experience longterm renal disease. Death occurs in rare circumstances when severe gastrointestinal, CNS, or renal complications are present.6 Treatment Customary treatment of nonprogressive HSP includes generous hydration, analgesia with acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and bed rest. Attention to renal function is particularly important if NSAIDs are used. Because the disease may be preceded by a streptococcal infection, a throat culture and antibiotic therapy may be indicated.' Corticosteroid use for HSP treatment is controversial. Corticosteroids (prednisone 1 to 2 mg/kg/day) are sometimes used for extensive gastrointestinal involvement and abdominal pain. Corticosteroids are not recommended for rash or joint pain alone.6 In most cases, the illness will resolve in 2 to 3 weeks without corticosteroid use. Some patients will have at least one recurrence of the rash within several weeks of onset.3 Serial urinalysis should be considered for all patients to assess occult renal disease." In patients with renal complications, referral to a nephrologist is required. Careful monitoring of serum and urinary laboratory values is essential and long-term follow up is indicated.

Treatment of nephritis secondary to HSP remains controversial. Corticosteroid therapy for renal involvement alone is not beneficial; however, combination therapy, which includes corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, is somewhat effective in treating advanced renal disease.1011 * Conclusion HSP is a relatively common and selflimited childhood illness. Clinician familiarity with the illnesses characteristic symptoms and clinical presentation aids diagnosis. A methodological evaluation of the patient and careful laboratory interpretation often solves the diagnostic dilemma and lessens the possibility of using unnecessary interventions and treatment.

REFERENCES

1. Schlossberg D: Fever and rash. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1996;10:101-09.

Daoud MS, Schanbacher CF, Dicken CH: Recognizing cutaneous drug eruptions. Postgrad Med 1998;104:101-15.

Zitelli Bj, Davis HW: Atlas of pediatric physical diagnosis, 3rd ed. St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby-year Book, Inc., 1997:203-37.

4. American Academy of Pediatrics: Summaries of infectious diseases. In: Red book: Report of the committee on infectious diseases. Elk Grove Village, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 1997;196-97.

5. Kalish R, Persing DH, Segreti J, et al.: How to recognize and treat tick-borne infections. Patient Care 1997;31:184-205.

Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB: Nelson textbook of pediatrics, 16th edition. Philadelphia, Pa.: W.B. Saunders Co., 2000:727-1142.

Sharieff GQ, Francis K, Kuppermann N: Atypical presentation of Henoch-Schoenlein purpura in two children. Am J Emerg Med 1997;15:375-77.

8. Finberg L Saunders manual of pediatric practice. Philadelphia, Pa.: W.B. Saunders Co., 1998:284-92.

9. Whyte DA, Van Why SK, Siegel NJ: Severe hypertension without urinary abnormalities in a patient with Henoch-Sch6oenlein purpura. Pediatr Nephrol 1997;11:750-51.

10. Iijima K, Ito-Kariya S, Nakamura H, et al.: Multiple combined therapy for severe Henoch-- Scho6en[ein nephritis in children. Pediatr Nephrol 1998;12:244-48.

11. Kraft DM, McKee D, Scott C: Henoch-Sch6oenlein purpura: A review. Am Fam Physician 1998;58:405-08.

Cheryl Cummings Stegbauer, CFNP, PhD Clinical Case Report Editor

Meghan P. Gustafson RN, CPNP, MSN

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Meghan P. Gustafson, RN, CPNP, MSN, is a pediatric nurse practitioner, emergency department, St. Louis Children's Hospital, Washington University Medical Center, St. Louis, Mo.

Copyright Springhouse Corporation Jul 2001

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved