Billed as "super aspirin" when they first came on the market nearly five years ago, Celebrex and Vioxx were widely touted as safer than other pain relievers. This is particularly relevant to people with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis who risk severe gastrointestinal bleeding and ulcers from chronic use of the older pain medications, such as aspirin, naproxen, ibuprofen, etc. Celebrex and Vioxx quickly became the alternatives, despite the lingering doubts about their purported safety. Cost has always been an issue, as each drug is about $3 a pill.

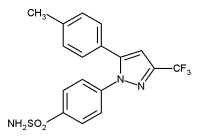

Celebrex (celecoxib) and Vioxx (rofecoxib) belong to a class of drugs called Cox-2 inhibitors (coxibs) because they inhibit an enzyme that is mostly responsible for pain and inflammation. Their combined sales now total $4.8 billion a year. As would be expected when any drug reaches blockbuster status, new and improved "second generation" coxibs--Bextra and Prexige--have appeared on the scene. The arrival of these drugs comes at a time when the growing body of evidence about the older coxibs has generated many more questions than answers.

Latest Studies

The latest study, which was conducted among members of one of the country's largest health-maintenance organizations, found that higher doses of Vioxx tripled the risk of heart attack or sudden cardiac death. As with most other coxib trials, Vioxx was compared with other pain relievers in a family of drugs called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that includes the most widely used painkillers, such as aspirin, naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn), ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil), diclofenac (Difenac), etc, sold generically and under numerous different brand names.

A large clinical trial assessing one of the second generation coxibs was published last month in the British journal The Lancet. The results clearly favored the newest coxib, Prexige, which lowered the odds of gastrointestinal damage without increasing the rate of heart problems. That did not, however, stop the accompanying editorial from questioning whether the drug--or any other coxib--is worth it:

Though many people swear by Celebrex and Vioxx, neither drug has been proven to be a more effective painkiller than any of the other * NSAIDs. Their purported advantage rests entirely on the claim of fewer gastrointestinal side effects. If true, this would be a major benefit because severe and sometimes fatal gastrointestinal bleeding can occur suddenly and without warning in people who are chronic users of NSAIDs.

But the manufacturers of Celebrex and Vioxx have not proven this benefit to the FDA's satisfaction, and the agency withheld permission to promote its safety advantage. What happened next was enough to destroy one's faith in drug companies, or at least one drug company--Pharmacia, manufacturer of Celebrex (now Pfizer is the producer).

In 2000, a study funded by Pharmacia was published in JAMA. It appeared to provide the proof that Celebrex caused fewer cases of gastrointestinal bleeding than either of two older NSAIDs. The 8,000 participants had been taking the drugs for six months.

One year later, the media reported that the participants had actually been followed for 12-15 months when JAMA published the study. The longer follow-up showed that the people taking Celebrex had a higher rate of gastrointestinal side effects than those taking ibuprofen. Pharmacia had apparently withheld the longer-term data to make its drug appear safer than it really is. That wasn't the only bad news. The longer follow-up also showed that the study participants who were taking Celebrex had a three-fold higher rate of serious heart problems than those on NSAIDs.

Vioxx has its own comparative trial in which people taking the coxib for nine months had twice the rate of serious heart problems than those taking naproxen. Researchers were left to speculate whether the findings of these two trials were due to the clot-busting effect of naproxen and ibuprofen or to the clot-causing effect of coxibs. Significantly, neither the Celebrex trial nor the Vioxx trial was designed to prove superior effectiveness as a painkiller. Both trials had been designed solely to prove a safety advantage.

In time, the question surrounding the frequent use of coxibs had shifted from: Do these drugs really cause fewer serious gastrointestinal adverse reactions? Now, the question has become broader: Do coxibs cause more non-gastrointestinal harm than the other NSAIDs?

Latest Studies Revisited

That brings us back to the studies published last month. The most recent Vioxx study was conducted at Kaiser Permanente, one of the country's largest health maintenance organizations. The greater incidence of heart attacks and sudden deaths among the enrollees taking higher doses of Vioxx (50 mg) led the Kaiser Permanente physician committee to announce that it may revise the HMO's coxib coverage policy within the next few weeks, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Most Vioxx users take daily doses of 12.5 to 25 mg, and the higher 50 mg dose is approved by the FDA for the treatment of pain for no more than five days. It is not unusual, however, for people to take the higher doses of Vioxx for much longer than five days. The Wall Street Journal reported that even at lower doses Vioxx appeared to have a stronger association with heart problems than Celebrex.

The Kaiser Permanente study was initiated and co-funded by the FDA. Though this study was presented at an international meeting of epidemiologists held in France last month and has yet to be published, the findings have already received considerable media coverage.

The largest coxib trial to date was published at the same time in The Lancet (8/21/04). The Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial (TARGET) compared the newest coxib, Prexige, with ibuprofen or naproxen. (Prexige has been approved recently in the United Kingdom and is expected to be approved in the USA in the near future.)

The intent of the TARGET was not only to see whether Prexige reduces gastrointestinal side effects, but also to answer lingering questions about heart-related adverse reactions. It was still not clear to researchers whether coxibs actually cause more heart problems than other NSAIDs, or whether there are simply fewer heart problems among people taking the drugs with which a coxib is usually compared (e.g., aspirin, naproxen, etc). TARGET was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, makers of Prexige.

More than 17,000 people over the age of 50 with osteoarthritis participated in the TARGET for one year. Compared to the people on NSAIDs, those taking Prexige had a three to four-fold reduction in ulcer complications but no increased rate in serious heart-related problems.

Drs. Topol and Falk, the above-quoted editorialists invited by The Lancet editors to comment on TARGET, put these findings in context. They explained that the Prexige lowered the odds of ulcer complications by less than 1% among the TARGET study participants who were not taking low-dose aspirin. (Participants taking daily low-dose aspirin to prevent heart disease were allowed to do so, as this is a common practice.) But Prexige increased their odds of having abnormal liver function test by 2%.

What's more, the editorial pointed out that the TARGET participants were not typical of the average chronic coxib user. Overall, they had fewer serious heart problems than most people over age 50. TARGET recruiters excluded nearly all people who had had a heart attack, stroke, coronary artery bypass surgery or congestive heart failure. No one had heart disease.

The TARGET findings confirmed earlier suspicions about naproxen a drug with which coxibs are often compared in clinical trials. The TARGET showed that naproxen does, in fact, have a heart-protective (clot-dissolving) effect--and that would explain the higher rate of heart problems in the coxib users in this and other trials. But this does not clearly exonerate Prexige, argued Drs. Topol and Falk, who cite smaller studies showing that the participants on the second generation coxibs had more heart attacks and strokes than the participants on the placebo. Also cited was a new study from Canada showing that the large increase in use of coxibs by people over age 66 was accompanied by a 10% increase in hospitalizations for upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Drs. Topol and Falk ended their critique by taking the FDA to task for not requiring coxib manufacturers to conduct trials that include people with cardiovascular disease--"a public health problem of great magnitude."

ENDNOTE: If Pfizer and Merck, the companies that make Celebrex and Vioxx, respectively, had proven their drugs to be superior painkillers or less likely to cause gastrointestinal damage, you can be sure these claims would appear in their ads.

The next time you see one of those ubiquitous ads for Celebrex or Vioxx, note what is missing. The ads will usually contain a sentence saying that the drug is effective in reducing pain and stiffness, but no claim that it is more effective than the cheaper non-prescription pain relievers. The word powerful turns up a lot in drug ads to imply superiority.

Be sure to read the ads' fine print. Here's what Merck says about the possible side effects of Vioxx: "Serious stomach problems, such as stomach and intestinal bleeding, can occur with or without warning symptoms. These problems, if severe, could lead to hospitalization or death." And this is how Pfizer puts it in Celebrex ads aimed at physicians: "Serious GI toxicity such as bleeding, ulceration, and perforation can occur with or without warning symptoms in patients treated with NSAIDs."

Brace yourself for a flood of ads featuring Bextra, the latest coxib to be approved in the U.S. And count on the words powerful, strength, and dramatic being used liberally.

* Celebrex and Vioxx are also NSAIDs.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Center for Medical Consumers, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group