While a growing body of evidence is showing that tens of millions of people around the world could benefit from taking statin drugs, economic factors are limiting the number of people who are actually receiving these drugs. And, though the discussion is focusing primarily on issues of cost-effectiveness and who should pay for the drugs, the statin story also reveals one of the uglier sides of the patent-medicine industry.

The scientific aspects of statin therapy are well documented: these drugs can significantly reduce the incidence of heart attack and stroke among high-risk patients, even those with normal or low serum cholesterol levels. Statin drugs are the first class of cholesterol-lowering agents that have been shown repeatedly and consistently to reduce both cardiac events and total mortality. Because other cholesterol-lowering drugs have produced little or no reduction in mortality, investigators believe that statins do more for the cardiovascular system than just lower cholesterol levels. Statins also exert an anti-inflammatory effect, as demonstrated by their capacity to lower levels of C-reactive protein, and recent evidence suggests that chronic inflammation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of coronary heart disease.

Statin drugs do cause side effects in some cases, and one such drug (cerivastatin; Baycol[R]) was removed from the market after it was found to cause fatal rhabdomyolysis, a severe breakdown of muscle tissue. Overall, however, the benefits of statin drugs appear greatly to outweigh their risks. Currently, approximately 25 million patients worldwide are receiving statins (13 million in the United States), but estimates are that at least 3 times as many people could benefit from these drugs.

The problem is that statins cost $2 to $3 per day in most markets, an amount that, even at current levels of "under-utilization," is straining the budgets of insurance companies and of countries that have national healthcare systems. And many people who do not have drug-reimbursement insurance are unable to afford these medications. So, it seems we are stuck with the choice of either allowing millions to die from heart attacks or strokes or of gradually transferring the world's wealth to the drug companies.

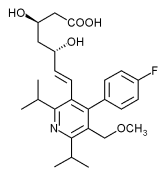

Fortunately, there may be a simple solution to this dilemma: give red yeast rice a chance. Red yeast rice is a condiment that has been used in China with apparent safety for more than 1,000 years. It is made by fermenting white rice with a strain of red yeast. Red yeast rice naturally contains modest amounts of lovastatin, the same compound that Merck & Co. patented as Mevacor[R], one of the first statin drugs to reach the market. Red yeast rice also contains 8 other compounds that inhibit hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA reductase (HMG CoA reductase), an action identical to that of lovastatin and the other statin drugs. In a double-blind trial, supplementation with 2.4 g/day of red yeast rice for 8 weeks lowered the mean LDL cholesterol concentration by 22.3% in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Because its mechanism of action appears to be similar to that of statins, it is likely that red yeast rice would have similar clinical benefits, as well.

For a brief period of time several years ago, a company called Pharmanex was marketing red yeast rice as a cholesterol-lowering agent. Merck & Co. filed a lawsuit, however, claiming that Pharmanex was violating Merck's patent on lovastatin. Although a judge ruled initially in favor of Pharmanex (indicating a belief that God owns the patent on natural substances), the ruling was later overturned, and the importation of red yeast rice from China was banned. By squelching red yeast rice, Merck & Co. forfeited any right to pretend that it cares about anything other than its own bottom line.

Since red yeast rice was banned, Mevacor[R] has fallen out of favor and the price of Merck stock has dropped by more than half (a karmic involution, perhaps). Pfizer, on the other hand, with its $8-billion-per-year drug Lipitor[R], is doing quite well, and other companies are competing vigorously for statin market-share.

A few small nutritional-supplement companies have obtained red yeast rice and are offering it for sale. Their red yeast strains appear to be different, however, from the product originally sold by Pharmanex, and concerns have been raised both about the safety and efficacy of the copycat products.

Those who have a vested interest in not giving all of their money to those who own the patents on statins can fight back. Governments and third-party payers can team up to fund a large-scale study comparing statin drugs with red yeast rice. It would not be surprising if the results showed that red yeast rice produces similar outcomes (with respect to cardiac events and mortality) and causes fewer side effects. In the meantime, it is important to acknowledge that the banning of red yeast rice was a mistake, and that we are now experiencing what political scientists and military analysts call "blow-back."

Alan R. Gaby, MD

COPYRIGHT 2004 The Townsend Letter Group

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group