How to fight "bad" cholesterol

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of death in the United States.1 Of the various CVDs, coronary heart disease (CHD) is by far the most common, causing more than 500,000 fatalities each year.2

Several factors contribute to the high incidence of CHD. Lifestyles endemic to industrialized countries-too little exercise, too much dietary fat, as well as an aging population-play a role. Fast food and a preference for super-sized portions overcome the body's natural metabolic resources, causing a build up of lipids (fats) and cholesterol in coronary arteries and the cardiovascular system.

Because high cholesterol and CHD are so common, you should understand the risk factors for heart disease, as well as the preventive therapies and medications. By recognizing the signs in those with CVD and those at risk, you can help patients incorporate healthier lifestyle habits.

Cholesterol: Good vs bad

The three types of lipids in the cardiovascular system are cholesterol, phospholipids, and triglycerides. Despite its sinister reputation, cholesterol is an essential molecule that helps cells to maintain their membrane structure and to function properly. The body manufactures its own cholesterol in the liver and also absorbs cholesterol from food. In some individuals, excess cholesterol can build up into a waxy, yellow substance, called plaque, which can clog the walls of the arteries. This process is called atherosclerosis.

One of the key risk factors for atherosclerosis is high cholesterol. Cholesterol, carried through the blood by lipoproteins, is classified by the lipoproteins' densities. About one-third to one-fourth of blood cholesterol is carried by high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C).3 This is considered "good" cholesterol because high levels (more than 60 mg/dL) of it seems to protect against CHD. Consequently, having low HDL cholesterol levels (less than 40 mg/dL) is also a risk factor for heart attack.3

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is considered the "bad" cholesterol, and high levels of LDL cholesterol (over 100 mg/dL, depending on risk factors) increase the risk for coronary disease and heart attack. Although LDL cholesterol is widely recognized as a factor for CHD, other lipoproteins, such as very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL-C) and intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL-C), also play a role that is only beginning to be understood by medical experts.3

Physicians perform a fasting lipid profile to check cholesterol levels. Other risk factors, such as familial history of heart disease, smoking, obesity, diabetes, and physical inactivity are taken into consideration. According to the American Heart Association (AHA), LDL cholesterol levels of less than 100 mg/dL is the standard goal. Low-density lipoprotein levels at 130 mg/dL or above are considered problematic for people with two or more risk factors. Total cholesterol levels of 200 mg/dL or less are desirable.4 The general term for excess fat and cholesterol in the blood is hyperlipidemia. In recent years, however, the term dyslipoproteinemia has become preferred because it considers other lipid abnormalities, particularly those distinguished by LDL cholesterol.

How the blood flows

Every cell in the body needs a constant supply of oxygen and nutrients to stay alive. Oxygen is delivered through the blood in the coronary arteries. This process is run continually by the body's circulatory system.

The primary circulatory system consists of the heart, blood, and blood vessels, which provide a constant How of blood through the body, delivering oxygen and removing carbon dioxide and waste from surrounding tissues.

The blood vessels of the circulatory system consist of two pathways: the pulmonary circuit, which carries blood from the heart to the lungs and back to the heart; and the systemic circuit, which moves blood between the heart and all other areas of the body.6

The cardiovascular system is a closed system.6 Upon inhalation, oxygen enters the lungs and is picked up by the blood. The oxygen-rich blood then moves through the pulmonary circuit to the heart, which pumps the blood to other tissues and organs through the systemic circuit. Once it reaches the tissue, oxygen is released, and carbon dioxide and wastes are picked up and returned to the heart and lungs.

When plaque builds up and narrows or blocks the arteries, the body is unable to deliver oxygen to the heart. If not enough oxygen reaches the heart, an individual may experience chest pain called angina. If the blood supply to a portion of the heart becomes blocked, or occluded, the result is a myocardial infarction (MI), or a heart attack.

Diet and exercise come first

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) warns that diets high in fat, particularly saturated fat, are associated with increased cholesterol and a greater risk for heart disease. To help lower cholesterol, the NIH recommends a diet that is low in saturated fat and cholesterol, with less than 7% of calories coming from saturated fat and less than 200 mg of dietary cholesterol per day. Foods low in saturated fat include lean meats, 1% dairy products, fish, skinless poultry, whole grain foods, and fruits and vegetables. High-cholesterol foods include egg yolk, organ meats, and full-fat dairy products.7

Mary Finn, CMA, RN, from the Bay Area Heart Center in St. Petersburg, Fla, emphasizes patient education as an important aspect for preventing and treating CHD. Part of her clinic's education program involves instructing people on reading food labels, teaching portion size, and learning how to prepare healthier, low-cholesterol foods. They also offer dietician-led grocery store tours to teach people how to shop and increase their nutritional awareness. But she warns not to overload people with information. "All of these changes all at once can be overwhelming to people," Finn says. "So we try to offer a little information at a time."

Another important aspect of preventing high cholesterol is exercise. According to the NIH, regular physical exercise can help lower a person's LDL cholesterol, and raise the HDL cholesterol levels.7

Most medical experts agree that 20 to 30 minutes of physical activity three or more times a week provide benefits against CHD. Since beginning an exercise program can be intimidating for those who previously have led sedentary lifestyles, it is important for health care professionals to inform patients that even small amounts of activity will benefit their cardiovascular health.

Kathryn Panagiotacos, CMA, at Harry W. Eichenbaum, MD, a private practitioner in St. Petersburg, Fla, agrees that exercise is an essential part of management of high blood cholesterol. Due to die large population of senior citizens in her community, Panagiotacos often sees older patients in her physician's office. She emphasizes that any amount of exercise, even stretches for people confined to wheelchairs, makes a difference. "The more they move, the better off they are," she says.

Besides diet and exercise, other risk factors for high cholesterol include cigarette smoking, obesity, diabetes, and heredity.3 Because heart disease often runs in families, familial history of high cholesterol and CHD should be considered along with cholesterol levels. "We see people who exercise and eat the right foods, and their cholesterol is horrible," says Nancy Whitaker, CMA, Brigham Medical Center, Brigham City, Utah. "Family history has a lot to do with it."

Statins: When all else fails

Although the best mechanisms for prevention and treatment of atherosclerosis are diet and exercise, they aren't always effective or properly followed. Sometimes high cholesterol levels don't drop, or if they do, not enough to reach target levels. Although lifestyle changes are the preferred way to reduce cholesterol, when they're not completely effective, lipid-reducing medications called statins are often prescribed.

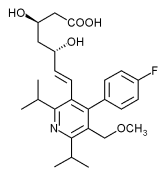

Statins lower the LDL cholesterol by blocking an enzyme (HGM-CoA reductase) that produces cholesterol. In some cases, statins also can modestly raise the level of HDL cholesterol, which helps move cholesterol back to the liver to be released as waste. Terry Moran, MD, of the Advanced Lipid Clinic at the Community Hospital of Monterey Peninsula in California, says HDL cholesterol acts as a "scavenger that looks for loose cholesterol and takes it back to the liver," preventing it from depositing in the arterial wall. Statins can also lower triglyceride levels (another risk factor for heart disease).4

Several statin drugs are currently on the US market: atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin. Another statin, cerivastatin, was withdrawn from the market in August 2001 after reports of muscle-related side effects.6

Studies on statins have been conducted on more than 50,000 people, and statins have been shown to reduce LDL cholesterol by 20% to 45%, depending on dosage.6 Clinical trials report that statin medication may decrease risk of CHD, heart attacks, stroke, and total mortality.6

Statins are usually taken in a single dose in the evening, between dinner and bedtime, to take advantage of the fact that the body produces more cholesterol at night. The usual starting dose is 20 mg.2 Dosage can be raised if cholesterol levels do not reach desired levels.

Although medications are effective at lowering cholesterol, modification of diet and exercise habits, in combination with drugs, achieves the best possible results. "We do get some people who think they can take medication and eat whatever they want," Finn says, and emphasizes that statins work best with lifestyle changes.

Watch for side effects

Like any drug, statin use can be associated with certain side effects. Minor symptoms often include nausea, diarrhea, and indigestion. However, these are usually mild and disappear as people adjust to the medication.

Although incidents of serious side effects are rare, occasionally they can occur. Most people tolerate statins well; however, a small percentage of people (0.$% to 2%)8 on statins can develop muscle pain, tenderness or weakness, which is a condition called myopathy. People who develop muscular symptoms should be taken off statin medication immediately. Severe myopathy may result in rhabdomyolysis, a muscle degenerative condition that may be fatal."

Statins can also cause liver abnormalities.5 These problems occur rarely, but the National Cholesterol Education Program recommends performing liver tests on patients after they start taking statins to make sure enzymes in the liver are not elevated. Regular tests on the liver can identify any problems early and reduce likelihood of serious damage.5

Keep yourself and patients informed

Once people are able to get their cholesterol levels within a healthy range, maintenance is the next step. Usually, a follow-up with the physician every six months is recommended, depending on a person's risk factors.

Certified Medical Assistants can help patients reach and maintain their goals by acknowledging that lifestyle modifications are not easy. At Finn's clinic, the staff rewards patients who have reached their target cholesterol levels with a "graduation celebration." "We recognize their work because we know it's tough," Finn says. The extra attention and one-on-one interaction help to keep patients on track.

One challenge CMAs face in educating patients is keeping their own knowledge current. Both Finn and Panagiotacos encourage CMAs to educate themselves by staying abreast of guidelines, attending relevant lectures, and working with their attending physicians as resources. "You feel more comfortable teaching when you're up on a subject," Finn says. Pharmaceutical representatives can be another excellent source of information.

Devoting time to patient education can be difficult, Finn says, "in part because it's not revenue generating." Even small actions, like recommending a website or an article for a patient can be useful. The Internet is another helpful avenue. "People come in a lot more educated because of the Internet," Finn notes.

Clinical studies show overwhelmingly that statin medication, in conjunction with proper diet and exercise, can significantly reduce the risk of developing coronary heart disease.

The rapidly increasing flood of new information regarding statin use can be confusing to health care professionals and patients alike. Fortunately, CMAs have a variety of tools and resources available to help them guide patients. The good news for patients is that statin medication can help treat and prevent CHD before coronary events, such as heart attack or stroke, may occur.

References

1. Davidson MH, Jacobson TA. How statins work: The development of cardiovascular disease and its treatment with 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewprogram/608. Accessed October 11, 2003.

2. Noonan D. You want statins with that? Newsweek. July 28, 2003:344-40.

3. Grundy SM. Low-density lipoprotein, non-high-density lipoprotein, and apolipoprotein B as targets of lipid-lowering therapy. Circ. November 2002;106:2526-2529.

4. American Heart Association. What's the difference between LDL and HDL cholesterol? Available at: http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=180. Accessed October 7, 2003.

5. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Third report of the expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/cholesterol/index.htm. Accessed October 7, 2003.

6. Merck, Sharp, Dohme. Anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system. Available at: http://www.mercksharpdohme.com/disease/heart/coronary_health/anatomy/home.html. Accessed October 3, 2003.

7. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. High blood cholesterol: What you need to know. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/chol/wyntk.htm. Accessed October 1, 2003.

8. Pasternak RC, Smith SC, Bairey-Merz CN, Grundy SM, Clecman JI, Lenfant C. ACC/AHA/NHLBI advisory on the use of and safety of statins. Circ. 2002;106:1024-1028.

Nicole Grasse is a Chicago-based writer. She has written about women's health issues for the Chicago Tribune.

Copyright American Association of Medical Assistants Jan/Feb 2004

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved