ABC of diseases of liver, pancreas, and biliary system

Gall stones are the most common abdominal reason for admission to hospital in developed countries and account for an important part of healthcare expenditure. Around 5.5 million people have gall stones in the United Kingdom, and over 50 000 cholecystectomies are performed each year.

Types of gall stone and aetiology

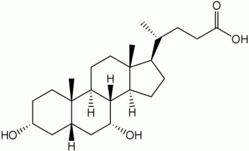

Normal bile consists of 70% bile salts (mainly cholic and chenodeoxycholic acids), 22% phospholipids (lecithin), 4% cholesterol, 3% proteins, and 0.3% bilirubin. Cholesterol or cholesterol predominant (mixed) stones account for 80% of all gall stones in the United Kingdom and form when there is supersaturation of bile with cholesterol. Formation of stones is further aided by decreased gallbladder motility. Black pigment stones consist of 70% calcium bilimbinate and are more common in patients with haemolytic diseases (sickle cell anaemia, hereditary spherocytosis, thalassaemia) and cirrhosis.

Brown pigment stones are uncommon in Britain (accounting for [is less than] 5% of stones) and are formed within the intraheptic and extrahepatic bile ducts as well as the gall bladder. They form as a result of stasis and infection within the biliary system, usually in the presence of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp, which produce [Beta] glucuronidase that converts soluble conjugated bilirubin back to the insoluble unconjugated state leading to the formation of soft, earthy, brown stones. Ascaris lumbricoides and Opisthorchis senensis have both been implicated in the formation of these stones, which are common in South East Asia.

Clinical presentations

Biliary colic or chronic cholecystitis

The commonest presentation of gallstone disease is biliary pain. The pain starts suddenly in the epigastrium or right upper quadrant and may radiate round to the back in the interscapular region. Contrary to its name, the pain often does not fluctuate but persists from 15 minutes up to 24 hours, subsiding spontaneously or with opioid analgesics. Nausea or vomiting often accompanies the pain, which is visceral in origin and occurs as a result of distension of the gallbladder due to an obstruction or to the passage of a stone through the cystic duct.

Most episodes can be managed at home with analgesics and antiemetics. Pain continuing for over 24 hours or accompanied by fever suggests acute cholecystitis and usually necessitates hospital admission. Ultrasonography is the definitive investigation for gall stones. It has a 95% sensitivity and specificity for stones over 4 mm in diameter.

Non-specific abdominal pain, early satiety, fat intolerance, nausea, and bowel symptoms occur with comparable frequency in patients with and without gall stones, and these symptoms respond poorly to inappropriate cholecystectomy. In many of these patients symptoms are due to upper gastrointestinal tract problems or irritable bowel syndrome.

Acute cholecystitis

When obstruction of the cystic duct persists, an acute inflammatory response may develop with a leucocytosis and mild fever. Irritation of the adjacent parietal peritoneum causes localised tenderness in the right upper quadrant. As well as gall stones, ultrasonography may show a tender, thick walled, oedematous gall bladder with an abnormal amount of adjacent fluid. Liver enzyme activities are often mildly abnormal.

Initial management is with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (intramuscular or per rectum) or opioid analgesic. Although acute cholecystitis is initially a chemical inflammation, secondary bacterial infection is common, and patients should be given a broad spectrum parenteral antibiotic (such as a second generation cephalosporin).

Progress is monitored by resolution of tachycardia, fever, and tenderness. Ideally cholecystectomy should be performed during the same admission as delayed cholecystectomy has a 15% failure rate (empyema, gangrene, or perforation) and a 15% readmission rate with further pain.

Jaundice

Jaundice occurs in patients with gall stones when a stone migrates from the gall bladder into the common bile duct or, less commonly, when fibrosis and impaction of a large stone in Hartmann's pouch compresses the common hepatic duct (Mirrizi's syndrome). Liver function tests show a cholestatic pattern (raised conjugated bilirubin concentration and alkaline phosphatase activity with normal or mildly raised aspartate transaminase activity) and ultrasonography confirms dilatation of the common bile duct ([is greater than] 7 mm diameter) usually without distention of the gall bladder.

Acute cholangitis

When an obstructed common bile duct becomes contaminated with bacteria, usually from the duodenum, cholangitis may develop. Urgent treatment is required with broad spectrum antibiotics together with early decompression of the biliary system by endoscopic or radiological stenting or surgical drainage if stenting is not available. Delay may result in septicaemia or the development of liver abscesses, which are associated with a high mortality.

Acute pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis develops in 5% of all patients with gall stones and is more common in patients with multiple small stones, a wide cystic duct, and a common channel between the common bile duct and pancreatic duct. Small stones passing down the common bile duct and through the papilla may temporarily obstruct the pancreatic duct or allow reflux of duodenal fluid or bile into the pancreatic duct resulting in acute pancreatitis. Patients should be given intravenous fluids and analgesia and be monitored carefully for the development of organ failure (see later article on acute pancreatitis).

Gallstone ileus

Acute cholecystitis may cause the gall bladder to adhere to the adjacent jejunum or duodenum. Subsequent inflammation may result in a fistula between these structures and the passage of a gall stone into the bowel. Large stones may become impacted and obstruct the small bowel. Abdominal radiography shows obstruction of the small bowel and air in the biliary tree. Treatment is by laparotomy and "milking" the obstructing stone into the colon or by enterotomy and extraction.

Natural course of gallstone disease

Two thirds of gall stones are asymptomatic, and the yearly risk of developing biliary pain is 1-4%. Patients with asymptomatic gall stones seldom develop complications. Prophylactic cholecystectomy is therefore not recommended when stones are discovered incidentally by radiography or ultrasonography during the investigation of other symptoms. Although gall stones are associated with cancer of the gall bladder, the risk of developing cancer in patients with asymptomatic gall stones is [is less than] 0.01%--less than the mortality associated with cholecystectomy.

Patients with symptomatic gall stones have an annual rate of developing complications of 1-2% and a 50% chance of a further episode of biliary colic. They should be offered treatment.

Management of gallstone disease

Cholecystectomy

Cholecystectomy is the optimal management as it removes both the gall stones and the gall bladder, preventing recurrent disease. The only common consequence of removing the gall bladder is an increase in stool frequency, which is clinically important in less than 5% of patients and responds well to standard antidiarrhoeal drugs when necessary.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been adopted rapidly since its introduction in 1987, and 80-90% of cholecystectomies in the United Kingdom are now carried out in this way. The only specific contraindications to laparoscopic cholecystectomy are coagulopathy and the later stages of pregnancy. Acute cholecystitis and previous gastroduodenal surgery are no longer contraindications but are associated with a higher rate of conversion to open cholecystectomy.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has a lower mortality than the standard open procedure (0.1% v 0.5% for the open procedure). This is mainly because of a lower incidence of postoperative cardiac and respiratory complications. The smaller incisions cause less pain, which reduces the requirement for opioid analgesics. Patients usually stay in hospital for only one night in most centres, and the procedure can be done as a day case in selected patients. Most patients are able to return to sedentary work after 7-10 days. This decrease in overall morbidity and earlier recovery has led to a 25% increase in the rate of cholecystectomy in some countries.

The main disadvantage of the laparoscopic technique has been a higher incidence of injury to the common hepatic or bile ducts (0.2-0.4% v 0.1% for open cholecystectomy). Higher rates of injury are associated with inexperienced surgeons (the "learning curve" phenomenon) and acute cholecystitis. Furthermore, injuries to the common bile duct tend to be more extensive with laparoscopic surgery. However, there is some evidence suggesting that the rates of injury are now falling.

Alternative treatments

Several non-surgical techniques have been used to treat gall stones including oral dissolution therapy (chenodeoxycholic and ursodeoxycholic acid), contact dissolution (direct instillation of methyltetrabutyl ether or mono-octanoin), and stone shattering with extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy.

Less than 10% of gall stones are suitable for non-surgical treatment, and success rates vary widely. Stones are cleared in around half of appropriately selected patients. In addition, patients require expensive, lifelong treatment to counteract bile acid in order to prevent stones from reforming, These treatments should be used only in patients who refuse surgery.

Managing common bile duct stones

Around 10% of patients with stones in the gallbladder have stones in the common bile duct. Patients may present with , jaundice or acute pancreatitis; the results of liver function tests are characteristic of cholestasis and a dilated common bile duct is visible on ultrasonography.

The optimal treatment is to remove the stones in both the common bile duct and the gall bladder. This can be performed in two stages by endocsopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy or as a single stage cholecystectomy with exploration of the common bile duct by laparoscopic or open surgery. The morbidity and mortality (2%) of open surgery is higher than for the laparoscopic option. Two recent randomised controlled trials have shown laparoscopic exploration of the bile duct to be as effective as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in removing stones from the common bile duct. Laparoscopic exploration has the advantage that the gall bladder is removed in a single stage procedure, thus reducing hospital stay. In practice, management often depends on local availability and skills.

In elderly or frail patients endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with division of the sphincter of Oddi (sphincterotomy) and stone extraction alone (without cholecsytectomy) may be appropriate as the risk of developing further symptoms is only 10% in this population.

When stones in the common bile duct are suspected in patients who have had a cholecystectomy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography can be used to diagnose and remove the stones. Stones are removed with the aid of a dormia basket or balloon. For multiple stones, a pigtail stent can be inserted to drain the bile; this often allows subsequent passage of the stones. Large or hard stones can be crushed with a mechanical lithotripter. When cholangiopancreatography is not technically possible the stones have to be removed surgically.

Risk factors associated with formation of cholesterol gall Stones

* Age [is greater than] 40 years

* Female sex (twice risk in men

* Genetic or ethnic variation

* High fat, low fibre diet

* Obesity

* Pregnancy (risk increases with number of pregnancies)

* Hyperlipidaemia

* Bile salt loss (ileal disease or resection)

* Diabetes mellitus

* Cystic fibrosis

* Antihyperlipidaemic drugs (clofibrate)

* Gallbladder dysmotility

* Prolonged fasting

* Total parenteral nutrition

Differential diagnosis of common causes of severe acute epigastric pain

* Biliary colic

* Peptic ulcer disease

* Oesophageal spasm

* Myocardial infarction

* Acute pancreatitis

Charcot's triad of symptoms in severe cholangitis

* Pain in right upper quadrant

* Jaundice

* High swinging fever with rigors and chills

Causes of pain after cholecystectomy

* Retained or recurrent stone (dilatation of common bile duct seen in only 30% of patients)

* Iatrogenic biliary leak or stricture of common bile duct

* Papillary stenosis or dysfunctional sphincter of Oddi

* Incorrect preoperative diagnosis--for example, irritable bowel syndrome, peptic ulcer, gastro-oesophageal reflux

Further reading

* Beckingham IJ, Rowlands BJ. Post cholecystectomy problems. In Blumgart H, ed. Surgery of the liver and biliary tract. 3rd ed. London: WB Saunders, 2000

* National Institutes of Health consensus development conference statement on gallstones and laparoscopic cholecystectomy Am J Surg 1993; 165:390-8

* Cuschieri A, Lezoche E, Morino M, Croce E, Lacy A, Toouli J, et al. EAES multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing two-stage vs single-stage management of patients with gallstone disease and ductal calculi. Sung Endosc 1999;13:952-7

Criteria for non-surgical treatment of gall stones

* Cholesterol stones [is less than] 20 mm in diameter

* Fewer than 4 stones

* Functioning gall bladder

* Patent cystic duct

* Mild symptoms

Summary points

* Gall stones are the commonest cause for emergency hospital admission with abdominal pain

* Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has become the treatment of choice for gallbladder stones

* Risk of bile duct injury with laparoscopic cholecystectomy is around 0.2%

* Asymptomatic gall stones do not require treatment

* Cholangitis requires urgent treatment with antibiotics and biliary decompression by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

[GRAPH OMITTED]

The ABC of diseases of the liver, pancreas, and biliary system is edited by IJ Beckingham, consultant hepatobiliary and laparoscopic surgeon, department of surgery, Queen's Medical Centre, Nottingham (Ian.Beckingham@nottingham.ac.uk). The series will be published as a book later this year.

COPYRIGHT 2001 British Medical Association

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group