Practice recommendations

* Patients with mild to moderate alcohol withdrawal symptoms and no serious psychiatric or medical comorbidities can be safely treated in the outpatient setting (SOR: A).

* Patients with moderate withdrawal should receive pharmacotherapy to treat their symptoms and reduce their risk of seizures and delirium tremens during outpatient detoxification (SOR: A).

* Benzodiazepines are the treatment of choice for alcohol withdrawal (SOR: A).

* In healthy individuals with mild-to-moderate alcohol withdrawal, carbamazepine has many advantages making it a first-line treatment for properly selected patients (SOR: A).

In our small community hospital--with limited financial and medical resources--we have designed and implemented an outpatient alcohol detoxification clinical practice guideline to provide cost-effective, evidence-based medical care to our patients, in support of their alcohol treatment. Those patients with mild-to-moderate alcohol withdrawal symptoms and no serious psychiatric or medical comorbidities can be safely treated in the outpatient setting. Patients with history of severe withdrawal symptoms, seizures or delirium tremens, comorbid serious psychiatric or medical illnesses, or lack of reliable support network should be considered for detoxification in the inpatient setting.

* THE PROBLEM OF ALCOHOL WITH DRAWAL

Up to 71% of individuals presenting for alcohol detoxification manifest significant symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. (4) Alcohol withdrawal is a clinical syndrome that affects people accustomed to regular alcohol intake who either decrease their alcohol consumption or stop drinking completely.

Physiology

Alcohol enhances gamma-aminobutyric acid's (GABA) inhibitory effects on signal-receiving neurons, thereby lowering neuronal activity, leading to an increase in excitatory glutamate receptors. Over time, tolerance occurs as GABA receptors become less responsive to neurotransmitters, and more alcohol is required to produce the same inhibitory effect. When alcohol is removed acutely, the number of excitatory glutamate receptors remains, but without the suppressive GABA effect. (5) This situation leads to the signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal.

Symptoms

Noticeable alcohol withdrawal symptoms may appear within hours of cessation or decreasing alcohol intake. The most common symptoms include tremor, craving for alcohol, insomnia, vivid dreams, anxiety, hypervigilance, agitation, irritability, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, headache, and sweating. (5) Even without treatment, most of these relatively benign symptoms resolve within hours to days.

More concerning are hallucinations, delirium tremens (DTs), and seizures. Transient auditory or visual hallucinations may occur within the first 2 days of decreasing or discontinuing alcohol consumption, and can be separate from DTs. DTs, which present within 2 to 4 days of the last drink (and can last up to 3 to 4 days), are characterized by disorientation, persistent visual and auditory hallucinations, agitation and tremulousness, and autonomic signs resulting from the activation of stress-related hormones. These signs include tachycardia, hypertension, and fevers.

DTs are much more serious than the "alcohol shakes"--5% of patients who experience DTs die from metabolic complications. (6) The occurrence of DTs is 5.3 times higher in men than in women; (7) however, women may exhibit fewer autonomic symptoms, making DTs in women more difficult to diagnose. (6)

Grand mal seizures can occur in up to 25% of alcoholics undergoing withdrawal. (4) If alcohol-related seizures do occur, they generally do so within 1 day of cessation of alcohol intake, but can occur up to 5 days later.

Risk factors for prolonged or complicated alcohol withdrawal include duration of alcohol consumption, the number of lifetime prior detoxifications, prior seizures, prior episodes of DTs, and current intense craving for alcohol. (6-10)

BEFORE TREATMENT: ASSESS AND STABILIZE

Initial assessment of the patient Before initiating treatment for alcohol withdrawal, perform a thorough assessment of the patient's medical condition. This evaluation should include an assessment of coexisting medical and psychiatric conditions, the severity of previous withdrawal symptoms, and the risk factors for withdrawal complications. The initial symptoms of alcohol withdrawal are not specific and may mimic other serious disease conditions; therefore, the initial assessment should exclude potentially serious medical and psychiatric comorbidities.

Initially, assessment of common alcohol-related medical problems should be conducted. These complications include gastritis, gastrointestinal bleeding, liver disease, cardiomyopathy, pancreatitis, neurological impairment, electrolyte imbalances, and nutritional deficiencies. A physical examination should be performed to assess for arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, hepatic or pancreatic disease, infectious conditions, bleeding, and nervous system impairment.

Initial alcohol level and urine drug screen should be assessed, as recent high levels of alcohol intake and substance abuse place the patient at higher risk for complications. Unstable mood disorders---delirium, psychosis, severe depression, suicidal or homicidal ideation--while potentially difficult to assess during intoxication, need to be considered and ruled out.

Stabilize the patient

After initial assessment, vital signs (eg, heart rate, blood pressure, and temperature) should be stabilized while fluid, electrolyte, and nutritional disturbances are corrected. Some patients undergoing alcohol withdrawal may require intravenous fluids to correct severe dehydration resulting from vomiting, diarrhea, sweating, and fever.

Alcoholics are often deficient in electrolytes or minerals, including thiamine, folate, and magnesium (although replacing magnesium makes no difference in clinically meaningful outcomes) (level of evidence [LOE]: 1, double-blind randomized controlled trial). (11) All patients being treated for alcohol withdrawal should be given 100 mg of thiamine immediately and daily (LOE: 3; insufficient evidence from randomized controlled trials to guide clinicians in the dose, frequency, route, or duration of thiamine treatment for prophylaxis against or treatment of WKS due to alcohol abuse) . (4) Thiamine should be given before glucose containing fluids, to avoid the risk of precipitating Wernicke syndrome (LOE: 3). (12)

Assess the severity of the withdrawal

Once a diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal is made, complete an assessment of the severity of withdrawal and the risk of complications. The best validated tool is the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol-Revised (CIWA-Ar) symptom scale (Figure 1). (10) This instrument rates 10 withdrawal features; it takes only a few minutes to administer and may be repeated when re-evaluation is necessary. CIWA-Ar scores of <8 are suggestive of mild withdrawal symptoms, while those >15 confer an increased risk for confusion and seizures.

CIWA-Ar is reliable, brief, uncomplicated, and clinically useful scale that can also be used to monitor response to treatment. It offers an increase in efficiency over the original CIWA-A scale, while retaining clinical usefulness, validity, and reliability. It can be incorporated into the usual clinical care of patients undergoing alcohol withdrawal and into clinical drug trials of alcohol withdrawal (strength of recommendation [SOR]=A]. (5,13)

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Patients experiencing more serious withdrawal (with CIWA-Ar scores >8) should receive pharmacotherapy to treat their symptoms and reduce their risk of seizures and DTs (SOR=A). (14)

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are the mainstay of treatment in alcohol withdrawal (number needed to treat [NNT]=17; data from large meta-analysis of 6 prospective, placebo-controlled trials) (SOR=A). (10,14-16) Like alcohol, these agents magnify GABA's effect on the brain. Benzodiazepines are cross-tolerant with alcohol; during withdrawal from 1 agent, the other may serve as a substitute. Benzodiazepines also reduce the incidence of DTs and seizures (Table 1). (5,14)

The most commonly used benzodiazepines are diazepam (Valium), chlordiazepoxide (Librium), and lorazepam (Ativan). All appear to be equally efficacious in treating alcohol withdrawal symptoms (LOE: 1; randomized controlled trial).

Longer-acting agents, such as chlordiazepoxide or diazepam, contribute to an overall smoother withdrawal course with lessened breakthrough or rebound symptoms, but they may also lead to excess sedation for patients with hepatic dysfunction.. (17-20) Shorter-acting benzodiazepines, such as oxazepam (Serax), may result in greater discomfort and more discharges against medical advice, because alcohol withdrawal symptoms tend to recur when serum benzodiazepine levels drop.

Anticonvulsants

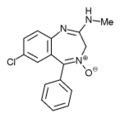

Attractive alternatives to benzodiazepines include the anticonvulsants carbamazepine (Tegretol) and valproic acid (Depakote).

Carbamazepine. Carbamazepine has been used successfully for many years in Europe, (21) but has not been used widely in the US due to the safety, efficacy, and familiarity of benzodiazepines (Table 1). The use of anticonvulsants, however, has several advantages. They are not as sedating as benzodiazepines and do not have the abuse potential, making them particularly useful in the outpatient setting.

The use of anticonvulsant medication decreases the possibility of seizures, one of the more serious complications of alcohol withdrawal (NNT=36) (LOE: 1, 2 double-blind randomized controlled trials). The brain cell kindling-like phenomenon-in which repeated episodes of alcohol withdrawal is associated with increasing severity of withdrawal--is decreased with the anticonvulsant carbamazepine. (14)

In a double-blind controlled trial comparing carbamazepine with oxazepam, carbamazepine was shown to be superior in ameliorating global psychological distress and reducing aggression and anxiety. (21) Stuppaeck et al showed that for alcohol withdrawal longer than 5 days, carbamazepine was statistically superior (P<.05) to oxazepam in reduction of CIWA scores. (22.23) Carbamazepine is also superior to benzodiazepines in preventing rebound withdrawal symptoms and reducing post-treatment drinking, especially in those with a history of multiple repeated withdrawals (SOR=A). (22) It has been shown that patients treated with carbamazepine were less likely to have a first drink following detoxification, and if they did drink, they drank less. This difference was especially evident for those patients with a history of multiple withdrawal attempts. (22)

A limitation of carbamazepine use, however, is its interaction with multiple medications that undergo hepatic oxidative metabolism, making it less useful in older patients or those with multiple medical problems. In summary, in generally healthy individuals with mild-to-moderate alcohol withdrawal, carbamazepine is just as efficacious as benzodiazepines, but has many advantages making it the drug of choice for properly selected patients (SOR=A). (21-23)

Valproic acid. Another widely used anticonvulsant, valproic acid, significantly affects the course of alcohol withdrawal and reduces the need for treatment with a benzodiazepine (LOE: 1). (24) Two double-blind, randomized studies showed that patients treated with valproic acid for 4 to 7 days had fewer seizures, dropped out less frequently, had less severe withdrawal symptoms, and require less oxazepam than those treated with placebo or carbamazepine. (24.25)

Although effective, valproic acid use may be limited by side effects--somnolence, gastrointestinal disturbances, confusion, and tremor-that mimic the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, malting it difficult to assess improvement.

Other types of medications

Alpha-adrenergic agonists, (24-30) beta-blockers, (31-33) and calcium channel blockers (34.35) have been used to control symptoms of acute alcohol withdrawal, but have demonstrated little efficacy in prevention of seizures or DTs (LOE: 1). (5.36)

TREATMENT REGIMENS

The acceptable medication regimens for treating alcohol withdrawal are the gradually tapering dose approach, the fixed-schedule approach, and the symptom-triggered approach. The first 2 regimens are appropriate for the pharmacological treatment of outpatient alcohol detoxification.

Gradually tapering regimen. With the gradual-dosing plan, patients receive medication according to a predetermined dosing schedule for several days as the medication is gradually discontinued (Table 2).

Fixed-schedule regimen. In the fixed-schedule dosing regimen, the patient receives a fixed dose of medication every 6 hours for 2 to 3 days regardless of severity of symptoms.

Symptom-triggered regimen. For the symptom-triggered approach, the patient's CIWA-Ar score is determined hourly or bihourly and the medication is administered only when the score is elevated. Typically, benzodiazepines are used in a symptom-triggered regimen, although either benzodiazepines or anticonvulsants may be used in a fixed-schedule plan.

The main advantage to the symptom-triggered approach is that much less medication is used to achieve the same withdrawal state (LOE: 1). (37-39) The symptom-triggered approach has also shown a possible decrease in DTs and may lead to less oversedation. (38.39)

We favor a symptom-based approach whenever adequate periodic assessment of CI-WA-Ar can be performed, such as in an inpatient setting. For those patients who require pharmacological treatment during outpatient detoxification (CIWA-Ar score 8-15), we prefer tile gradually tapering or fixed dosing plan, to provide a margin of safety, simplify the dosing schedule, and maximize compliance (SOR: C, expert opinion). (14)

INPATIENT VS OUTPATIENT TREATMENT

Most patients undergoing alcohol withdrawal may be treated safely in either an inpatient or outpatient setting (SOR=A). (40) Treatment professionals should assess whether inpatient or outpatient treatment would contribute more therapeutically to an alcoholic's recovery process. (41)

Patients with severe alcohol withdrawal symptoms (CIWA-Ar >15), previous history of DTs or seizures, or those with serious psychiatric or medical comorbidities should be considered for detoxification in an inpatient setting (SOR=B) (Table 3). (10,42) The main advantage of inpatient detoxification is the availability of constant medical care, supervision, and treatment of serious complications.

A major disadvantage is the high cost of inpatient treatment. Hayashida and colleagues found inpatient treatment to be significantly more costly than outpatient treatment ($3,319-$3,665 vs $175-$388). (43) Additionally, while inpatient care may temporarily relieve people from the social stressors that contribute to their alcohol problem, repeated inpatient detoxification may not provide an overall therapeutic benefit.

Most alcohol treatment programs find that <10% of patients need admission to an inpatient unit for treatment of withdrawal symptoms. (44) For patients with mild-to-moderate alcohol withdrawal symptoms (CIWA-Ar <15), and no serious psychiatric or medical comorbidities, outpatient detoxification has been shown to be as safe and effective as inpatient detoxification (SOR=A). (40) Additionally, most patients in an outpatient setting experience greater social support, and maintain the freedom to continue working or maintaining day-to-day activities with fewer disruptions, and incur fewer treatment costs. (41) When assessing a patient for suitability for outpatient detoxification, it is important to ascertain motivation to stay sober, ability to return for daily nursing checks, and presence of a supportive observer at home.

REFERENCES

(1.) Angell M, Kassirer JP. Alcohol and other drugs-toward a more rational and consistent policy. N Engl J Med 1994; 331:537-539.

(2.) Harwood, H. Updating Estimates of the Economic Costs of Alcohol Abuse in the United States: Estimates, Update Methods, and Data. Report prepared by The Lewin Group for the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2000.

(3.) Whitmore CC, Yi H, Chen CM, et al. Surveillance Report #58: Trends in Alcohol-Related Morbidity Among Short-Stay Community Hospital Discharges, United States, 1979-99. Bethesda, Md: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Division of Biometry and Epidemiology, 2002.

(4.) Myrick H, Anton RE Treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Health Res World 1998; 22:38-43.

(5.) Saitz R. Introduction to alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Health Res World 1998; 22:5-12.

(6.) Trevisan LA, Boutros N, Petrakas IL, et al. Complications of alcohol withdrawal pathophysiologic insights. Alcohol Health Res World 1998; 22:61-66.

(7.) Dvirskii AA. The role of genetic factors in the manifestation of delirium tremens [in Russian]. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova 1999; 99:48-50.

(8.) Fiellin DA, O'Connor PG, Holmboe ES, Horwitz RI. Risk for delirium tremens in patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Subst Abus 2002; 23:83-94.

(9.) Saunders JB, Janca A. Delirium tremens: its aetiology, natural history and treatment. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2000; 13:629-633.

(10.) Foy A, Kay J, Taylor A. The course of alcohol withdrawal in a general hospital. QJM 1997; 90:253-261.

(11.) Wilson A, Vulcano B. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of magnesium sulfate in the ethanol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1984; 8:542-545.

(12.) Victor M, Adams RD. The effect of alcohol on the nervous system. In: Metabolic and toxic diseases of the nervous system. Research publications of the Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Disease. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins, 1952.

(13.) Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneidennan J, Naranjo CA, Sellers EM. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: The revised Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict 1989; 84:1353-1357.

(14.) Mayo-Smith MF. Pharmacological management of alcohol withdrawal. A meta-analysis and evidence-based practice guideline. American Society of Addiction Medicine Working Group on Pharmacological Management of Alcohol Withdrawal. JAMA 1997; 278:144-151.

(15.) Holbrook AM, Crowther R, Lotter A, Cheng C, King D. Diagnosis and management of acute alcohol withdrawal. CMAJ 1999; 160:675-80.

(16.) Shaw JM, Kolesar GS, Sellers EM, Kaplan HL, Sandor P. Development of optimal tactics for alcohol withdrawal. I. Assessment and effectiveness of supportive care. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1981; 1:382-387.

(17.) Myrick H. Anton RF. Clinical management of alcohol withdrawal. CNS Spectrums 2000; 5:22-23.

(18.) Hill A, Williams D. Hazards associated with the use of benzodiazepines in alcohol detoxification. J Subst Abuse Treat 1993; 10:449-451.

(19.) Ritson B, Chick J. Comparison of two benzodiazepines in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal; effects on symptoms and cognitive recovery. Drug Alcohol Depend 1986; 18:329-334.

(20.) Holbrook AM, Crowther R, Lotter A, Cheng C, King D. Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of acute alcohol withdrawal. CMAJ 1999; 160:649-655.

(21.) Malcolm R, Ballenger JC, Sturgis ET, Anton R. Double-blind controlled trial comparing carbamazepine to oxazepam treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:617-621.

(22.) Malcolm R, Myrick H, Roberts J, et al. The effects of carbamazepine and lorazepam on single versus multiple previous alcohol withdrawals in an outpatient randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med 2002; 17:349-355.

(23.) Stuppaeck CH, Pycha R, Miller C, Whitworth AB, Oberbauer H, Fleischhacker WW. Carbamazepine versus oxazepam in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal: a double-blind study. Alcohol & Alcoholism 1992; 27:153-158.

(24.) Reoux JP, Saxon AJ, Malte CA, Baer JS, Sloan KL. Divalproex sodium in alcohol withdrawal: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001; 25:1324-1329.

(25.) Malcolm R, Myrick H, Brady KT, Ballenger JC. Update on anticonvulsants for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Am J Addict 2001; 10(Suppl):16-23.

(26.) Bjorkqvist SE. Clonidine in alcohol withdrawal. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1975; 52:256-263.

(27.) Wilkins AJ, Jenkins WJ, Steiner JA. Efficacy of clonidine in treatment of alcohol withdrawal state. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1983; 81:78-80.

(28.) Manhem P, Nilsson LH, Moberg AL, Wadstein J, Hokfelt B. Alcohol withdrawal: effects of clonidine treatment on sympathetic activity, the renin-aldosterone system, and clinical symptoms. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1985; 9:238-243.

(29.) Baumgartner GR, Rowen RC. Clonidine vs. chlordiazepoxide in the management of acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Arch Int Med 1987; 147:1223-1226.

(30.) Robinson BJ, Robinson GM, Maling TJ, Johnson RH. Is clonidine useful in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal? Alchol Clin Exp Res 1989; 13:95-98.

(31). Worner TM. Propranolol versus diazepam in the management of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome: double-blind controlled trial. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1994; 20:115-124.

(32.) Horwitz RI, Gottlieb LD, Kraus ML. The efficacy of atenolol in the outpatient management of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Results of a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med 1989; 149:1089-1093.

(33.) Kraus ML, Gottlieb LD, Horwitz RI, et al. Randomized clinical trial of atenolol in patients with alcohol withdrawal. N Engl J Med 1985; 313:905-909.

(34.) Banger M, Benkert 0, Roschke J, et al. Nimodipine in acute alcohol withdrawal state. J Psychiatr Res 1992; 26:117-123.

(35.) Altamura AC, Regazzetti MG, Porta M. Nimodipine in human alcohol withdrawal syndrome--an open study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1990; 1:37-40.

(36.) Saitz R, 0'Malley SS. Pharmacotherapies of alcohol abuse. Withdrawal and treatment. Med Clin North Am 1997; 81:881-907

(37.) Reoux JP, Miller K. Routine hospital alcohol detoxification practice compared with symptom triggered management with an Objective Withdrawal Scale (CIWA-Ar). Am J Addict 2000; 9:135-144.

(38.) Daeppen JB, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered versus fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162:1117-1121.

(39.) Saitz R, Mayo-Smith MF, Roberts MS, Redmond HA, Bernard DR, Calkins DR. Individualized treatment for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. JAMA 1994; 272:519-523.

(40.) Mattick RP, Jarvis T. In-patient setting and long duration for the treatment of alcohol dependence: out-patient care is as good. Drug Alcohol Rev 1994; 13:127-135.

(41.) Hayashida M. An overview of outpatient and inpatient detoxification. Alcohol Health Res World 1998; 22:44-46.

(42.) Booth BM, Blow FC, Ludke RL, Ross RL. Utilization of inpatient services for alcohol detoxification. J Men Health Adm 1996; 23:366-374.

(43.) Hayashida M. Alterman AI, McLellan AT, et al. Comparative effectiveness and costs of inpatient and outpatient detoxification of patients with mild-to-moderate alcohol withdrawal syndrome. N Engl J Med 1989; 320:358-365.

(44.) Abbott PJ, Quinn D, Knox L. Ambulatory medical detoxification for alcohol. Am f Drug Alcohol Abuse 1995; 21:549-563.

Alcohol detoxification in a community hospital

The problem. In our small community hospital, prior to the development of a clinical practice guideline, admissions for "inpatient alcohol detoxification" were among our top 5, with a select few patients making multiple, repeat visits. Additionally, we had no standardized, consistent strategy for initial emergency room evaluation; frequent early discharges against medical advice; multiple readmissions; infrequent and inconsistent entry into our outpatient Alcohol and Substance Abuse Program; and no existing process for primary care outpatient follow-up. We found ourselves in a situation where we were essentially enabling our patients in a destructive behavior. With no formal policy or guidelines, physicians tended to follow the path of least resistance: repeated short-stay admissions with limited therapeutic benefit.

The process. Our initial goal was to develop a standardized policy in an attempt to minimize the number of admissions of mild-to-moderate, uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal patients. Many of our patients are at low risk for serious complications, and we hoped to triage such individuals to an outpatient treatment setting. To organize the thought process, a flowchart was developed and refined. By incorporating current evidence, a clinical practice guideline was developed.

Evidence-based algorithm. We developed an evidence-based algorithm, Outpatient Treatment for Alcohol Detoxification (Figure 2), which uses a gradually tapering regimen, and allows providers to prescribe the medication they feel most appropriate given the clinical situation.

[FIGURE 2 OMITTED]

Results. In the 12 months since implementation of our clinical practice guideline, total alcohol-related admission decreased from 4 to 5 per month to only 1 during the entire period; furthermore, no patients treated with our guidelines were subsequently hospitalized for complications of alcohol withdrawal.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Dowden Health Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group