Background & objectives: Morbidity and mortality due to falciparum malaria are increasing in many tropical areas. The situation is further complicated by drug resistant malaria. The present study was undertaken to evaluate the efficacy of arteether on acute chloroquine resistant Plasmodiumfalciparum malaria in eastern coalfield area of Asansol.

Methods: A total of 30 patients with chloroquine resistant falciparum malaria smear and histidinerich protein II (HRPII) antigen positive were given arteether intramuscularly in a single daily dose of 150 mg (3mg/kg body weight in case of children) for three consecutive days. They were followed up to 28 days of arteether therapy. Each patient was assessed in terms of fever clearance time, parasite clearance time and parasite reappearance rate.

Results: The cure rate was found to be 100% with fever clearance time between 1-3 days (mean ± SD 48.2 ± 10.6h) and mean parasite clearance time of 1.2 ±0.3 days. Parasite reappearance rate was found to be 0%. No adverse effect due to arteether therapy was observed following the treatment.

interpretation & conclusion: The results indicated that arteether was effective in patients with acute chloroquine resistant, complicated as well as uncomplicated, falciparum malaria and might be considered as a suitable alternative to quinine.

Key words Artcclher - chloroquine resistant - efficacy - falciparum malaria

Morbidity and mortality due to Plasmodium falciparum malaria are increasing in many tropical areas'. The incidence of malaria worldwide is estimated to be 300 to 500 million clinical cases each year resulting in 1.1-2.7 million deaths. Of these, about 1 million are children

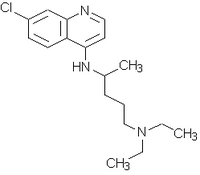

The only therapy of chioroquine resistant P. falciparum infections presenting with complications is administration of quinine. However, high incidence of side effects with quinine4 and advent of resistance to all known antimalarial drugs in current use has precipitated an urgent need for new anti malarial drugs5. Qinghaosu (artemisinin), a novel antimalarial drug was isolated from the plant Arlemisia anmta L6. It is a sesquiterpene lactone peroxide, structurally unrelated to other known antimalarial drugs. Three formulations viz., an oil based preparation for intramuscular injection (artemether and arteether), an unstable water soluable succinate salt (artesunate) and qinghaosu (artemisinin)4 have been used and are being investigated in different parts of the world. Arteether, artemether and artesunate are equally effective as far as rapidity of action and parasite clearence are concerned, injectable arteether is easy to administer as once daily dose and is convenient.

Clinical trials with qinghaosu derivatives in patients with P. falciparum malaria undertaken in Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, China, Tanzania and Nigeria7'9 showed that fever clearance and parasite clearance time were remarkably rapid but most of these clinical trials reported a very high recrudescence rate. Several studies3'4,10"13 have been carried out in India on the efficacy of arteether ([alpha],[beta]) in patients with uncomplicated and complicated P. falciparum malaria. The cure rate ranged from 93 to 1OO per cent with a rapid but variable parasite clearance and fever clearance time. Recrudescence rate ranged from 0-20 per cent. Studies on chloroquine resistant P. falciparum malaria have not been done especially in eastern part of India. Clinical experience with this drug in patients with chloroquine resistant and complicated malaria is very sparce14. The present study was therefore undertaken to evaluate the efficacy of arteether ([alpha],[beta]) in patients with acute chloroquine resistant P. falciparum infection in eastern India.

Material & Methods

This prospective study was carried out from February 2002 to January 2003 in the Central Hospital, Kalla, Asansol after obtaining approval from the hospital ethics committee. Planned as a pilot study, the sample size was decided on the basis of availability of patients and feasibility of investigations. Patients of various age groups (adults, children) presented with fever admitted in the medicine and paediatrics wards, slides positive for P. falciparum and diagnosed as a case of chloroquine resistant malaria, were included in the study. The patients were further confirmed by immunochromatographic test15. Patients who presented with fever and were positive for P. falciparum but could not complete the three doses of arteether therapy and were not confirmed cases of chloroquine resistant malaria were excluded. A total of 46 patients were positive for P. falciparum infection during the study period. Among these, six were not chloroquine resistant and five were seriously ill, treated with quinine and tetracycline and they were excluded from the study. Of the 35 patients included, two died after one dose of arteether therapy and three patients had taken discharge on their own risk before completion of arteether therapy. These five patients were also excluded. Written informed consent was taken from patients or their relatives before initiation of therapy.

Malaria diagnosis with thin and thick smear films'. Thin and thick smear blood films were stained with Giemsa (E. Merck, Mumbai, India) diluted 1:10 with phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.2). Stained slides were examined under a compound light microscope [Olympus, (India)Pvt. Ltd.,NewDelhi] using 1,00Oxoil immersion magnification. A maximum of 300 thick film fields were read before a slide was labelled negative. Parasitaemia levels were calculated with results from thick smear films as per recognized way of estimating the parasite count per µl in thick films. Thus parasites counted until 200 leucocytes were seen. The parasite count was multiplied by 40 to give parasite per µl of blood, as standard value 8000/µl for the white blood cell/µl was used16.

Histidine-rich protein II (HRP II) antigen detection of P. falciparum: HRP II antigen was detected by the commercial kit 'Para check ^sub pf^' (Orchid Biomedical Systems, Goa, India) using the principal of immunochromatographic test15.

Chloroquine resistant P. falciparum malaria: This was decided as per criteria of the World Health Organization17'18. Smear positive patient or relatives (in case of unconscious patients) were enquired about intake of chloroquine prior to hospitalization in the preceding 28 days period. Chloroquine was administered orally as per recommended doses [chloroquine 10 m g base/kg body wt (600 mg maximum dose) as a single dose followed by 5 mg/kg (300 mg maximum) at 6, 24 and 48 h^sup 19^] to the conscious and less sick patients (8 of 30 patients) who had no such history and thick blood film was examined on day 4. The type of resistance RII (following treatment, there was a reduction but no clearance of parasitaemia) or RIII (following treatment there was no reduction of paracitaemia) was determined comparing the pre- and post- treatment parasite count. Unconscious and seriously ill patients having no such history were excluded from this trial. A detailed history including clinical response after chloroquine therapy, day of chloroquine therapy before hospitalization, laboratory report if any etc., was taken from the patients or relatives (in case of unconscious patients) having the history of chloroquine intake before hospitalization and the type of resistance was determined accordingly17. Patients who had taken full course of chloroquine before hospitalization with high parasitaemia and no improvement of signs and symptoms were considered as RIII type chloroquine resistant. Of the 30 patients, 18 were RIII type, 10 RII type and 2 were RI type patients.

Biochemical examinations: Biochemical parameters were measured using semi automated RA-50 chemistry analyzer (Bayer Diagnostics Limited, Boroda, India) and reagents of Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd. (Mumbai, India).

Alpha-Beta arteether (E mal®, M/s Themis Chemicals Ltd., Mumbai, India) was administered to each patient by intramuscular route in a schedule of 150 mg once a day on three consecutive days (3mg/kg body weight in case of children below 12 yr). all patients remained hospitalized for a minimum of seven days period and thereafter each patient was evaluated for four weeks in outpatients department at weekly intervals. No other antimalarial drug was given during this period. Supportive measures such as blood transfusion, intravenous fluids, electrolytes etc., were provided according to need. Parasitological examination (thick and thin smear examination) for detection of malaria parasite and count was done initially on days O and 1,2, 3,7,14 and 28 post therapy. Clinical monitoring (symptom evaluations; adverse events with particular reference to neurotoxicity like gait disturbances, incoordination, respiratory depression, convulsions and cardiorespiratory arrest, others like hepatic and renal functions, electrocardiographic changes and allergic manifestations, physical examination) was performed in each case everyday during hospitalization to monitor the progress. Temperature was recorded at 6 hourly interval after initiation of arteether therapy. The Glasgow coma score20 was used for objective assessment in patients with cerebral malaria. Recovery from coma was considered to have occurred when the patient became conscious, responded to verbal commands and did not deteriorate further. The biochemical analysis included random blood sugar, serum urea, creatinine, bilirubin and haematological examinations like haemoglobin estimation and total and differential leucocytes count were performed in each case initially at day O and 7 post therapy and more frequently, if necessary.

The response of arteether therapy was measured in terms of fever clearance time, parasite clearance time and parasite reappearance rate.

Statistical analysis: Results of individual parameters were expressed as mean ± SD. Two way ANOVA (Friedman test -Non parametric) test was used to evaluate the significant differences of the pre- and posttreatment parasite count. Biochemical and haematological parameters were evaluated by Wilcoxon's signed Rank test and paired 't' test wherever appropriate. P value

Results & Discussion

A total of 30 patients (19 males, 11 females) microscopically and antigenically positive for P. falciparum infection and confirmed cases of chloroquine resistant malaria who completed the three doses of arteether therapy were included in the study. The age ranged between 3 to 60 yr (mean 31.6± 12.97 yr). Twenty patients presented with cerebral symptoms, 3 having fever associated with diarrhoea and remaining 7 had no cerebral symptoms or diarrhoea except chills and rigor.

Clinical examination showed that spleen was enlarged in 20 patients before initiating arteether therapy. The median Glasgow coma score was 9 (range 3-12); 8 patients had a score 3mg/dl) in 7 patients and higher serum urea (>50mg/ dl) and scrum crcatinine >1.5mg/dl) in 5 patients. Hb per cent was low (

In the present study a high cure rate (100%) was observed with mean parasite clearance time of 1.2±0.3 days fever controlled within 3 days of arteether therapy. In a study from Rourkela, Mohanty et aln showed a cure rate of 96 per cent in patients of complicated falciparum malaria. In a multicentric study Asthana et al4 showed an overall cure rate of 97 per cent in patients with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria. However, in the subsequent multicentric study by the same group3 in patients with complicated falciparum malaria a cure rate of 93 per cent was observed. A higher cure rate in the present study might be due to exclusion of patients not completing the three doses of arteether therapy and small number of study subjects. In a study from Dibrugarh" showed a cure . rate of 100 percent in 30 patients with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria but the recrudescence rate was 6.7 per cent. Mohanty et alu observed a very high recrudescence rate (20%) in patients with complicated falciparum malaria. In this present study, the recrudescence rate was not observed inspite of inclusion of both complicated and uncomplicated chloroquine resistant falciparum cases. Asthana et al4 also observed 100 per cent cure rate and no recrudescence in patients with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria. The overall recrudescence rate was very low (0.3%) in their subsequent multicentric study in patients with complicated falciparum malaria3. The parasite clearance time and fever clearance time in the present study were consistent with the earlier studies'110. A rapid recovery from coma was observed in the cerebral malaria patients in the present study. The mean coma recovery time was low compared to that reported in quinine treated patients21. This might be due to longer half-life as well as better accumulation of arteether in brain tissue14.

Another important observation in the present study was that the patients with haemolytic jaundice, acute renal impairment and severe anaemia recovered completely after arteether therapy and other supportive measures, as required. No adverse effect due to arteether therapy was observed in the study as has been noted by the earlier workers3,4-10-12.

In conclusion, arteether was found to be effective in patients with acute chloroquine resistant P.falciparum malaria. It was equally effective in patients with complicated as well as uncomplicated P. falcipanim malaria. Arteether may be considered as a suitable alternative to quinine because of its efficacy, safety and ease of administration, particularly for patients in peripheral hospitals with chloroquine resistant falciparum malaria. As this study was done with a limited number of patients, further studies with a larger sample size need to be done in other parts of India.

Acknowledgment

Authors thank Dr Rajbir Singh, Scientist, Department of Biostatistics, all India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, for statistical analysis of the data.

References

1. Nosten F, Vugt MV, Price R, Luxemberger C, Thvvay KL, Brockman A, et al. Effects of artesunate - mefloquine combination on incidence oc PIasmodhimfalciparum malaria and mefloquine resistance in western Thailand : a prospective study. Lancet 2000; 356 : 297-302.

2. World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Malaria. Twentieth report. Geneva: WHO; Technical report series no.892, 2000 p. 1-85.

3. Asthana OP, Srivaslava JS, Pandey TK, Vishwanalhan KA, Dcv V, Mahapatra KM, et al. Multicentric clinical trials for safety and efficacy evaluation of [alpha];[beta] arteether in complicated P. falcipanun malaria. J Assoc Physicians India 2001; 49 : 1155-60.

4. Asthana OP, Srivaslava JS, Kaniboj VP, ValechaN, Sharma VP, Gupla S, et al. A muliccntric study wilh arteclher in patients of uncomplicated Falciparum malaria. J Assoc Physicians India 2001; 49: 692-6.

5. Day KP. Malaria: A global threat. In: Krause RM, editor. Emerging infection: Biomedical research reports. New York: Academic Press; 1998 p. 463-97.

6. Hein TT, White NJ. Qinghaosu. Lancet 1993; Jj/ : 603-8.

7. Jiang JD, Li GQ, Guo XB, Kong YC. Antimalarial activity of mefloquine and qinghaosu. Lancet 1982; : 285-8.

8. Li GQ, Guo XG, Fu LC, Jian HX, Wang XH. Clinical trials of artemisin and its derivative in the treatment of malaria in China. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1994; 88 (Suppl. l ) : 55-6.

9. de Vries PJ, Dien TK. Clinical pharmacology therapeutic potential artemisinin and its derivatives in the treatment of malaria. Drugs 1996; 52 : 818-36.

10. Mishra SK, Asthana OP, Mohanty S, Patnaik JK, Das BS, Srivastava JS, et al. Effectiveness of [alpha],[beta] arleclher in acute falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Mec/ 1995; 89 : 229301.

11. Mohapatra PK. Khan AM, Prakash A, Mohanta J, Srivastava VK. Effect of artccther [alpha]/[beta] on uncomplicated falciparum malaria cases in upper Assam. Indian.J Med Res 1996; YOV : 284-7.

12. Mohanty S, Mishra SK, Satpathy SK, Das BS, Patnaik J. [alpha]-[beta] arteether for the treatment of complicated falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1997; 91 : 328-30.

13. Singh N, Shukla MM. AsthanaOP. Sharma VP. Effectiveness of alpha-beta arteether in clearing Plasmodium falciparum parasitcmia in central India (Madhya Pradesh). Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1998; 29 : 225-7.

14. Thate UM. ,Arteether in therapy of malaria. J Assoc Physicians India 2001; 49 : 687-90.

15. Garcia M, Kirimoama S, Marlborough D, Lcafasia J, Rieckman KH. Immunochromatographic test for malaria diagnosis. Lancet 1996; 347 : 1549.

16. Warhurst DC, Willims JE. Laboratory diagnosis of malaria. J Clin Palhol 1996; 49 : 533-8.

17. Dias D. The relentless fight against malaria-1. Medicine Update 2001; /O: 1-5.

18. World Health Organisation. Assessment of therapeutic efficacy of antimalarial drugs for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in areas with intense transmission; 1996. WHO/ NAL/96-1077.

19. White NJ, Breman JG. Malaria and Babesiosis. In : Isselbacher KJ, Martin JB, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Wilson JD, Kasper DL, editors. Harrison 's principles of internal medicine. 13th ed. New York: McGrawIIill lnc; 1994 p. 887-93.

20. Roper All. Trauma of the head and spine. In: Isselbacher KJ, Martin JB, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Wilson JD, Kasper DL, editors. Harrison 's principles of internal medicine. 13th ed. New York: McGraw Hill lnc; 1994 p. 2320-8.

21. Mohanti D, Ghosh K, Pathare AV, Karnad D. Dcfcriprone (Ll) as an adjuvant therapy for Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Indian J Med Res 2002; //J : 17-21.

P.K. Mandai, Nibha Sarkar* & Alok Pal**

Departments of Pathology & Microbiology, *Medicine, **Paediatrics, Central Hospital, Asansol, India

Received March 24, 2003

Reprint requests : Dr P.K. Mandai, Head, Department of Pathology & Microbiology, Central Hospital, Kalla, Asansol, West Bengal, India

e-mail: pankajasn@rediffmail.com

Copyright Indian Council of Medical Research Jan 2004

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved