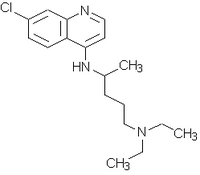

Chloroquine Overdosage in Infancy: A Case Report

Increased foreign travel and changes in the prevalence of malaria have made chloroquine more widely prescribed for prophylaxis. It is particularly important to ensure the appropriate doses of chloroquine are administered to children, because even small increases in the therapeutic dose may be toxic. Rapid absorption of the drug from the gastrointestinal tract produces sudden clinical symptoms after overdosage. Cardiac and neurologic abnormalities are the most important acute consequences of excess chloroquine.

Chloroquine (Aralen) is widely used for malaria prophylaxis and is increasingly used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. It has been estimated that more than 1 million Americans take chloroquine weekly for malaria prophylaxis.1

The potential for chloroquine overdosage is high, because small increases in the therapeutic dose can produce toxicity.2 Rapid absorption of chloroquine from the gastrointestinal tract produces sudden, severe clinical symptoms after overdosage.3

Of the numerous possible manifestations of chloroquine toxicity (Table 1), the cardiac effects have been most widely reported.2-8 Cardiopulmonary arrest may occur within two hours of chloroquine ingestion, particularly in children.2 The history is vital in distinguishing these cases from other causes of cardiovascular collapse, such as near-miss sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

Fortunately, chloroquine overdosage is rarely encountered in family practice. However, the need for vigilance is demonstrated by the following case, which occurred in a small town in Kansas.

Illustrative Case

During an afternoon nap at home, a previously healthy seven-week-old female infant was found to be apneic with blue discoloration of the lips and face. She had appeared normal a few minutes earlier, apart from "throaty sounds like congestion." The child's parents began artificial respiration, which was continued by paramedics from the local emergency medical service.

The infant was intubated at the local hospital and then transferred to a regional medical center. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was continued throughout the hour between discovery and arrival at the medical center. On admission, the infant was awake and breathing through the endotracheal tube on 50 percent oxygen. The only abnormality on physical examination was sluggish reactivity of the pupils.

Initial management was concerned with the potential diagnoses of septic shock, near-miss SIDS and seizure disorder. Therefore, an intensive investigation was performed, including cultures of blood, urine, throat secretions and cerebrospinal fluid, a chest radiograph, an electrocardiogram (EKG), an electroencephalogram and computed tomographic scanning of the head. The only abnormalities detected were nonspecific changes on the EKG and signs of early pulmonary edema on the chest radiograph.

A detailed history revealed that the family was on leave from a mission in Zaire and had begun chloroquine prophylaxis that morning in preparation for their return to Africa. The infant had been given five 1-ml droppers full of a 10 percent chloroquine elixir, i.e., 5 mL of a 100 mg base per mL solution. The instructions on the prescription from Zaire were "5 gtt par semaine," or five drops per week. The infant's ingested dose of chloroquine was equivalent to approximately 100 mg per kg.

Subsequent management included the administration of activated charcoal and magnesium citrate, and the infant's condition was monitored in the pediatric intensive care unit. No further complications occurred, and the infant was dismissed in good health on the fourth day after admission. No follow-up was performed, because the child returned to Africa with her family.

Pharmacology and Toxicology

Chloroquine blocks enzymatic synthesis of DNA and RNA in susceptible strains of malaria and extraintestinal amebiasis. The drug is readily absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and is about 50 percent protein-bound. Chloroquine has a very large volume of distribution; it accumulates in the lungs, kidneys, liver and spleen, and it binds strongly to melanin-containing cells in the eyes and the skin.4 Excretion is primarily renal. However, chloroquine is eliminated very slowly, and it may be detected in the tissues even a few years after the last dose.9

The therapeutic adult dose for malaria prophylaxis is 300 mg base per week, and the pediatric dose is 5 mg base per kg.10 The margin of safety for chloroquine is narrow. For adults, as little as 2.25 to 3 g may be a fatal dose. Estimates place the fatal dose for children in the range of 30 to 50 mg base per kg.

The toxic side effects of chloroquine are dose-related. Serum levels of less than 2.5 mg per L have not been associated with serious side effects. Serum levels of 2.5 to 5 mg per L are associated with neurologic symptoms and EKG disturbances. Doses leading to a serum level greater than 5 mg per L are associated with neurologic symptoms, as well as cardiovascular and EKG abnormalities, because of the quinidine-like effects of chloroquine.11

Final Comment

The near-fatal episode outlined in the illustrative case focuses attention on several critical issues. First, it is extremely important to obtain an accurate history of drug ingestion, even for infants, and to solicit information about family background, including travel history and lifestyle. Second, it is essential to communicate clearly to parents the dosage of a medication intended for their child. The importance of a high index of suspicion for drug overdosage, even in the most unlikely situations, is also apparent.

REFERENCES 1. Lobel HO, Campbell CC, Pappaioanou M, Huong AY. Use of prophylaxis for malaria by American travelers to Africa and Haiti. JAMA 1987;257:2626-7. 2. Childhood chloroquine poisonings--Wisconsin and Washington. MMWR 1988;37(28):437-9. 3. Di Maio VJ, Henry LD. Chloroquine poisoning. South Med J 1974;67:1031-5. 4. Cann HM, Verhulst HL. Fatal acute chloroquine poisoning in children. Pediatrics 1961;27: 95-102. 5. Riou B, Barriot P. Rimailho A, Baud FJ. Treatment of severe chloroquine poisoning. N Engl J Med 1988;318:1-6. 6. Robinson AE, Coffer AI, Camps FE. The distribution of chloroquine in man after fatal poisoning. J Pharm Pharmacol 1970;22:700-3. 7. McCann WP, Permisohn R, Palmisano PA. Fatal chloroquine poisoning in a child: experience with peritoneal dialysis. Pediatrics 1975; 55:536-8. 8. Don Michael TA, Aiwazzadeh S. The effects of acute chloroquine poisoning with special reference to the heart. Am Heart J 1970;79:831-42. 9. Rubin M, Berstein HN, Zvailfler NJ. Studies on the pharmacology of chloroquine. Arch Ophthalmol 1963;170:80-7. 10. Recommendations for the prevention of malaria in travelers. MMWR 1988;37(17):277-84. 11. Frisk-Holmberg M, Bergkvist Y, Domeij-Nyberg B, Hellstrom L, Jansson F. Chloroquine serum concentration and side effects: evidence for dose-dependent kinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1979;25:345-50.

Table : 1 Clinical Effects of Chloroquine Overdosage

COPYRIGHT 1989 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group